21st.—The ladies are now engaged making sand-bags for the fortifications at Yorktown; every lecture-room in town crowded with them, sewing busily, hopefully, prayerfully. Thousands are wanted. No battle, but heavy skirmishing at Yorktown. Our friend, Colonel McKinney, has fallen at the head of a North Carolina regiment. Fredericksburg has been abandoned to the enemy. Troops passing through towards that point. What does it all portend? We are intensely anxious; our conversation, while busily sewing at St. Paul’s Lecture-Room, is only of war. We hear of so many horrors committed by the enemy in the Valley—houses searched and robbed, horses taken, sheep, cattle, etc., killed and carried off, servants deserting their homes, churches desecrated!

Saturday, April 21, 2012

“We hear of so many horrors committed by the enemy in the Valley—houses searched and robbed, horses taken, sheep, cattle, etc.,”—Diary of a Southern Refugee, Judith White McGuire.

Written from the Sea islands of South Carolina.

Pope’s Plantation, St. Helena Island, April 21,1862.

You do not know what perfect delight your letter gave me, when I got it after I had done hoping for it. Everybody else got their letters two days before and I thought I should have to go to the plantation without hearing, and once there I should never be sure of a letter again, gentlemen’s pockets being our only post. But it was handed to me while I was packing at Mrs. Forbes’, and later in the evening when I was being driven by Mr. Hooper in about half a buggy, with a skin-and-bone horse, across cotton-fields, a voice from the roadside hailed us — “Have you got Miss Towne there? Here’s a letter for her. Came up with the groceries. Don’t know why or where from. Don’t know when.” It was from Ellen, and Mr. Eustis[1] had rescued it from the groceries accidentally. In the dark there Mr. Eustis welcomed me to Secesh Land, and I have seen him once or twice since. He and his son are both well and in the highest spirits. Indeed, everybody here is well as possible, better than ever in their lives before, and most of them in excellent spirits. And as for safety, you may be sure we feel pretty secure when I tell you that we sleep with the doors unlocked below, just as we used to think it so wonderful to do at Jasper’s. But I shall put the padlock on my door, and as soon as there is any way of locking the doors below, I shall do it. Now there are no keys and no bolts.

In Beaufort — “Befit” the negroes call it, or “Bufed” — there is less security, or folks think there is, for they lock up, and Mr. F. was always getting up reports of rebel boats stealing by, but they, all turned out to be fishermen. Stories of danger are always being circulated, but they come from waggish soldiers, I think. They said that on one island the rebels had landed and carried away a lady. There was not a word of truth in it, and just before we came here two regiments were ordered out to receive the Michigan regiment which had been fighting at Wilmington Island. Some one asked what they were called out for and they said the rebels had landed in force at Ladies’ Island, — Mr. Eustis’, where we were going that afternoon. I drove that very evening over across part of Mr. Eustis’ place in the dark with one little darky, Cupid by name, and I never saw a more peaceful place, and never was safer.

I think from the accounts of the negroes that this plantation is a healthy one. Salt water nearly encircles it at high tide. On the left are pines, in front a cottonfield just planted, to the right the negro quarters, a nice little street of huts which have recently been whitewashed, shaded by a row of the “Pride of China” trees. These trees are just in bloom and have very large clusters of purple flowers — a little like lilacs, only much more scattering. There is a vegetable garden also to the right and plenty of fig trees, one or two orange trees, but no other fruit. We have green peas, though, and I have had strawberries. Behind the house there are all kinds of stables, pig-pens, etc.

The number of little darkies tumbling about at all hours is marvellous. They swarm on the front porch and in the front hall. If a carriage stops it is instantly surrounded by a dozen or more woolly heads. They are all very civil, but full of mischief and fun. The night we arrived Mr. Pierce had gone about five miles to marry a couple. One of the party wore a white silk skirt trimmed with lace. They had about half a dozen kinds of cake and all sorts of good things. But the cake was horrid stuff, heavy as lead.

But I am going on too irregularly. I will first describe the family and then tell you, if I have time, about my coming and my future prospects.

Miss Donelson and Mrs. Johnson are going home tomorrow. I shall be very sorry to miss them, for I have shared their room and found them very pleasant friends. I have got really attached to Miss Donelson, whom I have seen most of, and I beg her to stay and go with Ellen and me to another plantation. But she, after being very undecided, has just determined to go home. You know, of course, that Ellen is coming. Mr. Pierce said he wrote for us to come together, but so as to make sure, he has given me another pass which I shall forward by Miss Johnson, and then, if Ellen still perseveres, we shall be together here after all.

It is not very warm here, I can tell you. To-day the thermometer is only 63, and I have worn my black cloth vest and zouave jacket every day, being too cold the only day I put on my black silk.

Miss Susan Walker is a very capable person, I think, and she proposes taking charge of the plantation hands and the distribution of the clothing. Miss Winsor is quite pretty and very sensible. She has the school-children to teach and is most efficient and reliable. Ellen will teach the adults on this plantation. I shall — just think of it! — I shall keep house! Mr. Pierce needs a person to do this for him. The gentlemen of the company are always coming here for consultation and there will be a large family at any rate — Mr. Pierce, Miss Walker, and we three younger ones, with young Mr. Hooper, who is Mr. Pierce’s right-hand man. We shall have visitors dropping in to meals at all hours, and the kitchen is about as far off as Mrs. Lambert’s from you; the servants untrained field hands, — and worse, very young girls, except the cook, — and so I shall have a time of it. I am also to do copying or be a kind of clerk to Mr. Pierce, and to be inspector of the huts. I shall begin by inculcating gardens.

This is not a pretty place, but the house is new and clean, about as nice as country-houses in Philadelphia, without carpets, though, and with few of the civilized conveniences. We shall have no ice all through the summer, and the water is so thick that it must be filtered, which will make it warm. That is the worst inconvenience I see. We are at no expense at all here. The hands on the place are obliged to work. All who can be are kept busy with the cotton, but there are some women and young girls unfit for the field, and these are made to do their share in housework and washing, so that they may draw pay like the others — or rations — for Government must support them all whether they work or not, for this summer. So far as I have seen, they are eager to get a chance to do housework or washing, because the Northerners can’t help giving extra pay for service that is done them, even if it is paid for otherwise, or by policy. One old man — Uncle Robert — makes butter, and we shall have plenty of it as well as milk. Eggs are scarce. These things belong to the plantation and are necessary to it. We do not pay for them. Robert brought in a tally stick this morning, grinning, to Miss Walker and showed how many days’ work he had done — rather wanting pay, I think. Miss Walker said, “We have paid part in clothes, you know, Uncle Robert, and the Government will take care you have the rest some day.” “Oh, I know it, ma’am,” he said, and he explained that he only wanted her to see how many days he had worked. He is very old, but should certainly be paid, for he takes care of all the stock on the place, if he does not work the cotton. Neither is he our servant; he only makes the butter for us and for sale (which goes to the support of the company expenses), and this is a small part of his work.

So matters are mixed up. Mr. Pierce has no salary and Government gives him only subsistence and pays all his expenses — nothing more. So he is entitled to comfortable living, and this we shall profit by. I suppose he is determined to do as Anna Loring asked — take especial care of me, for he has established me where I shall have the fewest hardships. When I say that we shall profit by it, I mean that we must necessarily share his comforts. For instance, our ration of candles is one-half a candle a week. Now, Mr. Pierce must have more than this, and we, downstairs in the parlor, see by his light. That is, we have common soldiers’ rations, and he, officers’, or something equivalent. I could not be more fortunately placed, it seems now, but if I find I cannot do what I came for in this position, that is, influence the negroes directly, I shall go somewhere else, for I find we can choose. Mr. Eustis cannot have any lady there, the house being only a larger sort of cabin, with only three rooms in all. Many of the ladies will go home in summer, but not because the place is unhealthy. They only came, like Mrs. Johnson, to stay awhile so as to start this place, and others came who were not suitable. Mrs. French’s object was to write a book and she thinks she has material enough now.

All the people here say it is healthy on these islands, but the plantations inland are deadly. I am on an island in a nice new house, and I do not think there will be any necessity for leaving. But if it should begin to get sickly here, we have only to go to St. Helena’s village on this same island (but higher and in pine trees; more to the sea also) to be at one of their “watering-places” and in an undoubtedly healthy situation. There are no negroes there, though, and so we shall have no work there.

The reason why soldiers are more likely to suffer is that they have to live in tents. Just think of the heat in a tent! I was at the Cavalry Camp at Beaufort and in the tent of Mrs. Forbes’ son. It was a pretty warm day, but there was a charming sea breeze. The tent did not face towards the wind, and the heat was insufferable in it — and the flies as bad as at Easton, I should fancy.

Mr. Pierce has just brought me some copying and so maybe I shall not be able to finish this letter.

It is one o’clock and I have been scribbling all the evening for Secretary Chase’s benefit, and so have to neglect my own family. I have had no time to write in my journal for several days, which I regret very much.

[1] F. A. Eustis, of Milton, Massachusetts, part owner of a plantation on Ladies’ Island.

Headquarters Porter’s Division, 3d Army Corps,

Camp Winfield Scott, April 21, 1862.

DEAR FATHER, — By orders from headquarters the name of this camp has changed to Camp Winfield Scott. Ever since we landed at Fort Monroe our camps have been called by number in regular order. Our first camp at Hampton was No. 1, etc. This camp, properly No. 5, has been called as above, and McClellan means to honor the camp and the general whose name we have adopted for it, by winning a splendid victory.

Guns are being taken by the camp this evening to be mounted on our earthworks. It will still take some few days to get everything in readiness. The roads are in a terrible state from the rain, and hence additional labor is entailed on the men and horses, and necessitates still further delay. New sites for batteries are constantly being selected by General Porter, and when we do get ready, the rebels will have to “keep their eyes peeled.” We can see them mounting additional guns every day, and strengthening their works. In the end I suppose it will result in giving us a few more cannon to add to the list of prizes taken.

Last night, for the first time I believe since we have been here, I was not waked up by any firing. The enemy kept themselves quietly within their works.

The men in this division have a great deal of fatigue duty to perform, such as mounting guns, making roads through the woods and digging earthworks. It is really fatigue duty, especially in this storm. They seem to stand it very well, however.

There is nothing especially new going on. . . .

Some of our men crept up so close to the rebel pickets last night that their relief guard passed within ten feet of them. They also heard some of their conversation. One man crept along the bank of the river until he heard the sound of oars. He waited until the boat touched the shore, when an officer jumped out and was met by another officer who came out of the bushes, and spoke to the first one, about crossing by the mill with some horses. The wind blew so that he could hear no more of their conversation. I don’t know what the conversation referred to.

General Porter is General McClellan’s favorite general, and McClellan often calls for him to go out and reconnoitre, etc., with him. The night I carried those dispatches to McClellan, he said, “My God ! if I can’t depend on Fitz John’s division, I don’t know what I can depend on.” He showed very plainly how highly he thought of General Porter and his division by his conversation. He was very pleasant to me indeed. I saw Captain Mason 1 on his staff the other day. He is from Boston, you know. . . .

Beckley’s farm near Raleigh, Virginia, Monday, April 21.— A. M. All night a high wind and driving cold rain; mud in camp deep. Like the Mount Sewell storm of September last. All day rain, rain — cold, cold rain. Rode to Raleigh, called on Colonel Scammon and Lieutenant-Colonel Jones and Major Hildt of Thirtieth. Talked over the troubles between the men of the Twenty-third and the men of [the] Thirtieth. The talk very satisfactory.

APRIL 21ST.— A calm before the storm.

Monday, 21st—Our camp is becoming more unhealthy all the time, and the odor from the battlefield at times is very disagreeable. This is the result of the heavy rains followed by warm weather.

Troops are arriving here every day and going on to the front. The army is advancing on Corinth, Mississippi, and we hear that there is almost continuous skirmishing between the outposts of the two armies.

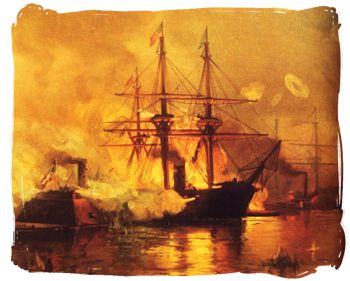

April 21st. At 1 o’clock this morning our gunboats returned, having succeeded in cutting the chain and setting two schooners adrift. At 3 o’clock all hands were aroused to ward off a large fire raft which among many others the enemy had sent adrift for our destruction, but like its predecessors it passed by harmless.

21st. A rainy day. Felt most sick, feverish, took a blue pill. Did not do much during the day.

21st—Occasional firing between the batteries on Warwick Creek to-day, without results worth noting. Sickness among the troops rapidly increasing. Remittent fever, diarrhœa, and dysentery prevail. We are encamped in low, wet ground, and the heavy rains keep much of it overflowed. I fear that if we remain here long we shall lose many men by sickness.

This neck of land, between Yorktown and Jamestown, it seems now is to be made the point d’appui of the armies in Virginia. If we can, and will break up this army, it will put an end to the war, and until this army is overcome or dispersed, be it a month or a year, there will be no progress in the direction of a satisfactory peace. We are getting forward our siege guns, concentrating forces, in a word, preparing for battle. My request to be relieved of the Brigade Surgeonship is to-day granted, and I return to the charge of my regiment.

Camp near Yorktown, Va.,

Monday, April 21, 1862.

Dear Sister L.:—

Father writes encouragingly about the war; thinks it is progressing rapidly and hopes I will soon be on my way home. Home! What will that be to me, do you think Mr. P., now that you have taken away its greatest attraction? There was always a blank there when she was gone and now she has gone to return no more except as a transient visitor. Henceforth, it will be a home to me no more. If I survive this war, do you know, C, that I’ve almost determined to quit roving, adopt farming as a business, and work steadily and perseveringly till I have a comfortable home for myself and the best woman I can find who will marry a soldier. I’m almost afraid that when we get home and the girls see what rough, sunburned and disgusting fellows we are—I’m afraid soldiers will be at a discount. Yes, my dreams of the pleasures of an exciting life are passing away and I have almost come to believe that the plain honest farmer who surrounds his home with comforts is the happiest man. How I wish I could live near you and that we could grow up into substantial, prosperous farmers together! But why be building castles in the air, when, perhaps, the bullet is even now rammed home to lay me under the sod on the field of Yorktown? I would not, if I could, unveil the future and see my fate. Still it has always seemed to me that I should escape death on the field. A wound has seemed more than probable. Indeed, I would not shun it, but it has ever seemed to me that I would not be called to sacrifice my life, yet such may be my fate. If so, I am content. Farewell, sweet dreams of life and love! Traitors are striking at the citadel of our beloved country. My life may check their murderous course and it must be given.

The papers are full of prophecies of the Waterloo that is to be fought here, the greatest battle of the war, and of course, a great Union victory. They don’t tell the date of the coming battle, however. Now, if you ask what I think of it, I should answer, “It isn’t coming off till after Richmond is taken.” And then it will not be the great affair the New York papers are making out. I will give my reasons for thinking so. I judge from the present state of things and from McClellan’s acknowledged skill in planning. He is a careful, cautious man and will not sacrifice lives in a fierce battle when time and skill will accomplish the same purpose. “Look at the situation,” as the papers say. McClellan lands 150,000 men at Fortress Monroe and sets out for Richmond. At Yorktown the rebels have fortifications extending across the Peninsula to the James. Here is the only place they can hope to hold against our forces. Here then they rally. All their forces are few enough to check such an army, and so they are all brought here. Manassas is deserted and now not 5,000 men are left between that and Richmond. All their army that lay along the Rappahannock was transferred to Yorktown, and they had scarcely gone when McDowell appeared at Fredericksburg with 40,000 men and Banks was following them down the Shenandoah valley with 70,000. An army of 100,000 is thus marching on Richmond, while we keep the rebel army here. It is, no doubt, repugnant to their feelings to see things go in this way, but what can they do? If they fall back to Richmond they will have a quarter of a million to fight without fortifications, for we shall certainly follow them up. If they grow desperate enough to come out from their forts and attack us, we outnumber them and they admit our courage, so they would inevitably be whipped at that. If they lie still awaiting an attack, they will lose Richmond, and wake some fine morning to find an army of 100,000 in their rear and McClellan at last ready to crush the rebellion.