April 28.—To-day a detachment of the First New-Jersey cavalry carried into Washington, D. C, ten prisoners captured at a courier station, six miles beyond the Rappahannock River, Va. They were surprised in their beds. The information which led to their capture was volunteered by a loyal black, who guided the Jerseymen through the rebel picket line. The prisoners declared that they were of the party who killed Lieut. Decker, near Falmouth. They were intelligent men of a company formed in John Brown times, to which “none but gentlemen were elected.”—N. Y. Tribune, April 29.

—The United States war steamer Sacramento was launched at the Portsmouth, (N. H.) Navy Yard to-day. She is the finest and largest war vessel ever built at Portsmouth.—Boston Transcript, April 29.

—Five companies of National cavalry had a skirmish with the enemy’s cavalry two miles in advance of Monterey, Tenn.[1] The rebels retreated. Five of them were killed—one a major. Eighteen prisoners, with horses and arms, were captured. One of the prisoners, named Vaughan, was formerly foreman in the office of the Louisville Democrat. The Unionists had one man wounded and none killed. The prisoners say that the enemy has upward of eighty thousand men at Corinth, and will fight and that they are intrenching and mounting large guns.—Official War Despatch.

—Near Yorktown, Va., Gen. Hancock went out with a portion of his brigade for the purpose of driving the rebels from a piece of timber which they occupied in close proximity to the National works. The troops advanced through an open fire on their hands and knees until they came within close musket-range. The rebels, who were secreted behind stumps and trees, were anxious to get the men on their feet, and to accomplish this the captain in command of the enemy shouted at the height of his voice to charge bayonets, supposing that the Union troops would instantly jump to their feet and run. But they were mistaken. The command being given the second time, the rebels arose, when the Union troops poured into them a well-directed fire, causing them to retreat, leaving their dead and wounded.

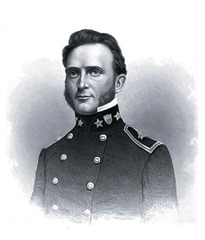

Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson

During the skirmish a new battery which the rebels had erected during Sunday night, and which interfered with the working party of the Nationals, was most effectually silenced and the guns dismantled.

—The Santa Fe, New-Mexico mail, arrived at Kansas City, Mo., with dates to the twelfth inst. Col. Slough and Gen. Canby formed a junction at Galisteo on the eleventh. Major Duncan, who was in command of Gen. Canby’s advance-guard, encountered a large party of Texans and routed them. Major Duncan was slightly wounded. The Texans were thirty miles south of Galisteo, in full flight from the territory.—Official Despatch.

—The rebel steamer Ella Warley (Isabel) arrived at Port Royal, S. C, in charge of Lieut. Gibson and a prize crew, she having been captured by the Santiago de Cuba, one hundred miles north of Abaco.

—Forts Jackson and St Philip on the Mississippi River, below New-Orleans, surrendered to the National fleet under Flag-Officer Farragut.— (Doc. 149.)

[1] Monterey is a small post-village of McNairy County, situated near the boundary line of Mississippi but a short distance from Corinth. The county has an area estimated at five hundred and seventy square miles, and occupies part of the table-land I between the Tennessee and Hatchie Rivers.

![]()