“Wilson Small,” May 16.

Dear Friend, — I have asked every one within reach what day of the week it is: in vain. Reference to Mr. Olmsted, who knows everything, establishes that it is Friday. Is it one week, or five, since I left New York?

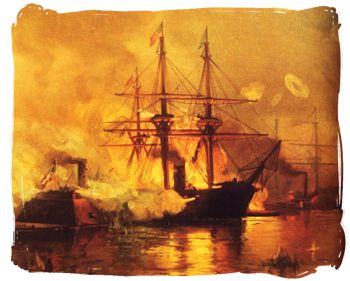

As I wrote the last words of my last letter, the “Elizabeth,” our supply-boat, came alongside with Mr. Olmsted and Mr. Knapp, and just behind them a steamer with one hundred and eighty sick on board. All hands were at once alert. The sick men were to be put on board the “Knickerbocker,” whither we all went at once, armed with our precious spirit-lamps. Meantime Mr. Olmsted read a telegram we had received in his absence, saying that a hundred sick were lying at Bigelow’s Landing and “dying in the rain.” Mr. Knapp took charge of the “Elizabeth,” saying, “Who volunteers to go up for them?” Three young men, Miss Helen Gilson, and I followed him. Not a moment was lost, — Mr. Knapp would not even let me go back for a shawl, — and the tug was off.

The “Elizabeth” is our store-tender or supply-boat. Her main-deck is piled from deck to deck with boxes. The first thing done is to pick out six cases of pillows, six of quilts, one of brandy, and a cask of bread. Then all the rest are lowered into the hold. Meantime I make for the kitchen, where I find a remarkable old black aunty and a fire. I dive into her pots and pans, I wheedle her out of her green tea (the black having given out), and soon I have eight bucketsful of tea and pyramids of bread and butter. Miss Gilson and the young men have spread the cleared main-deck with two layers of quilts and rows of pillows a man’s length apart, and we are ready for the men some time before we reach them; for the night is dark and rainy, and the boat has got aground, and it is fully ten o’clock before the men are brought alongside. The poor fellows are led or carried on board, and stowed side by side as close as can be. We feed them with spoonfuls of brandy and water; they are utterly broken down, soaked through, some of them raving with fever. After all are laid down, Miss Gilson and I give them their suppers, and they sink down again. Any one who looks over such a deck as that, and sees the suffering, despondent attitudes of the men, and their worn frames and faces, knows what war is, better than the sight of wounds can teach it. We could only take ninety; twenty-five others had to go on the small tug which accompanied us. Mr. Knapp, the doctor, and one of the young men went on board of her. Meantime the “Elizabeth” started on the homeward trip, so that Miss Gilson and I and a quartermaster were left to manage our men alone. Fortunately only about a dozen were very ill, and none died. Still, I felt anxious: six were out of their minds; one had tried to destroy himself three times that day, and was drenched through and through, having been dragged out of the creek into which he had thrown himself just before we reached him.

We were alongside the “Knickerbocker” by 1 A.M., when Dr. Ware came on board and gave me some general directions, after which I got along very well. It was thought best to leave the poor wearied fellows to rest where they were until morning, and the night passed off quietly enough; my only disaster being that I gave morphia to a man who actually screamed with rheumatism and cramp. I supposed morphia could n’t hurt him, and it was a mercy to others to stop the noise. Instead of this, I made him perfectly crazy. He rose to his feet in the midst of the prostrate mass of men, and demanded of them and of me his “clean linen” and his “Sunday clothes.” I picked my way to him, but could do nothing at first but make him worse. At last I was inspired to say that I had all his clothes “there” (pointing to a dark corner behind a bulkhead): “would he lie down and wait till I brought them?” To my surprise he subsided. I hid in trepidation for a few minutes, and at last, to my great joy, I saw the morphine take effect. One little fellow of fifteen, crushed by a tree falling on his breast, had run away from his mother, and was very pathetic. I persuaded him to let me write to her.

The next morning, after getting them all washed, I went off guard, and Mrs. Griffin and Miss Butler came on board with their breakfast from the “Knickerbocker,” where the hundred and eighty whom we had left arriving the night before, were stowed and cared for. Getting them all washed, as I say, is a droll piece of work. Some are indifferent to the absurd luxury of soap and water, and some are so fussy. Some poor faces we must wash ourselves, and that softly and slowly. I started along each row with two tin basins and two bits of soap, my arm being the towel-horse. Now, you are not to suppose that each man had a basinful of clean water all to himself. However, I thought three to a basin was enough, or four, if they did n’t wash too hard. But an old corporal taught me better. “Stop, marm!” said he, as I was turning back with the dirty water to get fresh; “that water will do for several of us yet. Bless you! I make my coffee of worse than that.”

Soon after breakfast my men were transferred to the “Knickerbocker.” She still lies alongside, and we take care of her. She is beautifully in order. The ward-masters are all excellent, and the orderlies know their duty. The men look comfortable, and even cheerful. It is a pleasure to give them their meals. I gave the men in the long ward (where they lie on mattresses in two rows, head to bead, two hundred of them) their dinner to-day, and their supper yesterday. Ah, me! how they liked it, — some of them, of course, too worn to do more than swallow a few spoonfuls and look grateful; others loud in their satisfaction. The poor, crazy man who tried to destroy himself at Bigelow’s Landing has some vague idea about me now; and sometimes, when he utterly refuses his milk-punch, and thrashes and splutters at every one who comes near him, I am sent for, when he subsides into obedience with a smile which is meant to be bland, and is so comical that people around retire in convulsions.

To-day I am “loafing.” Everything is in perfect order on the “Knickerbocker;” and as I scent a transfer this afternoon of the whole corps to the “Spaulding,” to fit her up, I am determined to husband my efforts. This boat, the “Wilson Small,” is finally smashed up; we call her the “Collida.” The hospital-boats usually lie alongside of each other, with their gangways connected; and sometimes we run through four or five boats at a time.

Captain Curtis is still on board, doing well. He goes North on the “Knickerbocker” to-day. Now that our wounded men are gone, we have a dinner-table set, and the Captain lies in his cot on one side of the cabin, laughing at the fun and nonsense which go on at meals. Mrs. Howland. has her French man-servant, Maurice, on board. He is capital. He struggles to keep us proper in manners and appearance, and still dreams of les convenances. At dinner-time he rushes through the various ships and wards: “My ladies, j’ai un petit plat; je ne vous dirai pas ce que c’est. I beg of you to be ponctuelle; I gif you half-hour’s notis.” The half-hour having expired, he sets out again on a voyage of entreaty and remonstrance. He won’t let us help ourselves, and if we take a seat not close to the person above, he says: “No, no, move up; we must have order.” His petit plat proved to be baked potatoes, which were received with acclamation, while he stood bowing and smiling with a towel (or it may have been a rag) for a napkin. But I must tell you that Maurice is the tenderest of nurses, and gives every moment he can spare to the sick. He serves his mistress, but he is attentive to all, and, like a true Frenchman, he so identifies himself with the moment and its interests that he is, to all hospital intents and purposes, “one of us.”

You are not to be alarmed by the word “typhoid,” which I foresee will occur on every page of my letters, nearly all our sick cases being that or running into that. The idea of infection is simply absurd. The ventilation of these ships is excellent; besides, people employed in such a variety of work and in high health and spirits are not liable to infection. Nobody ever thinks of such a thing, and I only mention it to check your imagination. In a boat organized like the “Knickerbocker,” we women stand no regular watch, but we are on hand at all hours of the day, relieving each other at our own convenience. As for the ladies among whom my luck has thrown me, they are just what they should be, — efficient, wise, active as cats, merry, light-hearted, thoroughbred, and without the fearful tone of self-devotion which sad experience makes one expect in benevolent women. We all know in our hearts that it is thorough enjoyment to be here, — it is life, in short; and we wouldn’t be anywhere else for anything in the world. I hope people will continue to sustain the Sanitary Commission. Hundreds of lives are being saved by it. I have seen with my own eyes in one week fifty men who must have died without it, and many more who probably would have done so. I speak of lives saved only; the amount of suffering saved is incalculable. The Commission keeps up the work at great expense. It has six large steamers running from here. Government furnishes these and the bare rations of the men; but the real expenses of supply fall on the Commission, — in fact, everything that makes the power and excellence of the work is supplied by the Commission. If people ask what they shall send, say: Money, money, stimulants, and articles of sick-food.