August 3— Remained in camp. A train laden with soldiers passed here to-day, going to Gordonsville.

Friday, August 3, 2012

“The enemy have considerable force some thirty or forty miles from us, amounting possibly to 30,000 men.”–Letters from Elisha Franklin Paxton.

August 3, 1862.

For some days I have been expecting that every mail would bring me a letter from home, but have been disappointed. I am sure a letter is on the way, and that you would not suffer two weeks to pass without writing to me. I wrote to you some ten days ago, just after I got here. It may be this did not reach you, and you do not know where I am. I am getting to feel used to the army and to the idea of staying in it until I see the end of the war, or it sees the end of me. The work entrusted to me is highly honorable and very agreeable. I think it will be sufficient to keep me employed and make me as happy as I have ever been in the service. The only objection to it is that my labor is gratuitous and I draw no pay. I shall try and make my expense account as small as possible. The army is more quiet than I have ever known it. The enemy have considerable force some thirty or forty miles from us, amounting possibly to 30,000 men. Their cavalry and ours are occasionally skirmishing, and yesterday had quite a severe engagement with one of our regiments at Orange C. H. They are said to have had some three regiments against our one, and, so far as I can learn, we got the worst of it. No very serious damage, however, as our killed and wounded are only fifteen.

To-day—Sunday—is very quiet, and reminds me much of a Sunday at home, the usual work being suspended. Formerly everything went on as usual on any day, but now the drills and ordinary work of the week are suspended on Sunday. Whilst employment here will make me contented, for there is no use in grieving about what must be borne, yet I heartily wish that I was at home with you and our dear little children. Affection and sympathy attract me towards home as the dearest place on earth, but duty to my country and respect for my own manhood require that I should forego this happiness until the war ends—as end it must, sooner or later. I trust, darling, that you will be as contented and happy as you can under the circumstances. The inconveniences to which you are subjected are just the same which all other ladies have to bear. You, at least, have all the comforts of home and necessaries of life, whilst the wife and little ones of many a gallant man in the service are exiles from their homes or without the necessaries of life. It is a poor consolation for your own troubles that others have worse; but it is alike the dictate of piety and virtue to bear them in patience, and thus show that you merit a better fate. The war must end some day. “We may never live to see it. But we owe to ourselves to cherish the hope that we may one day live happily together again, and there will be bright sunshine after the storm which now envelops us.

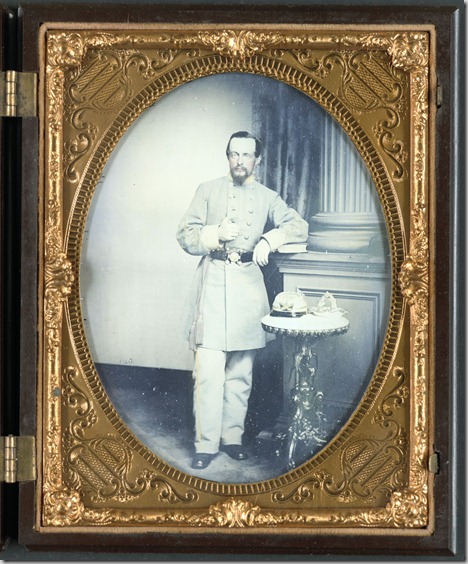

Library of Congress image:

- Title: Captain George Riggs Gaither of K Company, 1st Virginia Cavalry

- Creator(s): Rees, Charles R., photographer

- Date Created/Published: [between 1861 and 1863]

- Medium: 1 photograph : half-plate ambrotype, hand-colored ; 15.9 x 12.6 cm (case)

- Summary: Photo shows identified soldier with arm resting on book at the base of a column; a table next to him holds his cap and a dish. Exhibit caption: George Riggs Gaither (1831-1899), whose ancestors founded Gaithersburg, Maryland, is the subject of this ambrotype by Richmond-based Charles R. Rees, one of the best Civil War era photographers in the South. As captain of a local militia unit, the Howard County Dragoons, Gaither led a group of landowners, many of whom owned slaves, and assisted with peacekeeping in Baltimore during riots in 1861. When pressed to swear allegiance to the United States, most refused, gathered their weapons, rode to Leesburg, Virginia, and joined the Confederate Army. Gaither was captured at Manassas Junction on August 27, 1862, later exchanged, and sent to Europe the next year on a mission for the Confederate government. Following the war, he became a cotton trader.

- Ambrotype/Tintype filing series (Library of Congress) Liljenquist Family collection

August 3d, Westover.

Enfin nous sommes arrivées! And after what a trip! As we reached the ferry, I discovered I had lost the pass, and had to walk back and search for it, aided by Mr. Tunnard, who met me in my distress, as it has always been his luck to do. But somebody had already adopted the valuable trifle, so I had to rejoin mother and Miriam without it. The guard resolutely refused to let us pass until we got another, so off flew Mr. Tunnard to procure a second — which was vastly agreeable, as I knew he would have to pay twenty-five cents for it, Yankees having come down as low as that, to procure money. But he had gone before we could say anything, and soon returned with the two-bits’ worth of leave of absence. Then we crossed the river in a little skiff after sundown, in a most unpleasant state of uncertainty as to whether the carriage was waiting at the landing for us, for I did not know if Phillie had received my note, and there was no place to go if she had not sent for us. However, we found it waiting, and leaving mother and Miriam to pay the ferry, I walked on to put our bundles in the carriage. A man stepped forward, calling me by name and giving me a note from Charlie before I reached it; and as I placed my foot on the step, another came up and told me he had left a letter at home for me at one o’clock. I bowed Yes (it was from Howell; must answer to-morrow). He asked me not to mention it was “him”; a little servant had asked his name, but he told her it was none of her business. I laughed at the refined remark, and said I had not known who it was — he would hardly have been flattered to hear I had not even inquired. He modestly said that he was afraid I had seen him through the window. Oh, no! I assured him. “Well, please, anyhow, don’t say it’s me!” he pleaded most grammatically. I answered, smiling, “I did not know who it was then, I know no more now, and if you choose, I shall always remain in ignorance of your identity.” He burst out laughing, and went off with, “Oh, do, Miss Morgan, forget all about me!” as though it was a difficult matter! Who can he be?

We had a delightful drive in the moonlight, though it was rather long; and it was quite late when we drove up to the house, and were most cordially welcomed by the family. We sat up late on the balcony listening for the report of cannon, which, however, did not come. Baton Rouge is to be attacked to-morrow, “they say.” Pray Heaven it will all be over by that time! Nobody seems to doubt it, over here. A while ago a long procession of guerrillas passed a short distance from the house, looking for a party of Yankees they heard of in the neighborhood, and waved their hats, for lack of handkerchiefs, to us as we stood on the balcony.

I call this writing under difficulties! Here I am employing my knee as a desk, a position that is not very natural to me, and by no means comfortable. I feel so stupid, from want of sleep last night, that no wonder I am not even respectably bright. I think I shall lay aside this diary with my pen. I have procured a nicer one, so I no longer regret its close. What a stupid thing it is! As I look back, how faintly have I expressed things that produced the greatest impression on me at the time, and how completely have I omitted the very things I should have recorded! Bah! it is all the same trash! And here is an end of it — for this volume, whose stupidity can only be equaled by the one that precedes, and the one that is to follow it. But who expects to be interesting in war times? If I kept a diary of events, it would be one tissue of lies. Think! There was no battle on the 10th or 11th, McClellan is not dead, and Gibbes was never wounded! After that, who believes in reliable information? Not I!

Tuscumbia, Ala., August 3, 1862.

Tuscumbia, Ala., August 3, 1862.

In the last 15 days I have only written you once; partly because I have been so busy, more, because of my laziness. There is but little save rumors that can be of any interest to you from here, and shall not inflict any of them on you, for the newspapers have certainly surfeited everyone’s taste for that article. All this blowing and howling we have in the papers of raids everywhere, and overwhelming forces of the enemy confronting us at all points, is, I candidly believe, part of the plan to raise volunteers. It certainly is one grand humbug as far as this field is concerned. Every officer here that knows anything about the condition of the enemy, their positions and numbers, believes that if our army were concentrated and set at the work, we could clear out all the enemy south of this and west of Georgia in a short two months. The soldiers are all anxious to begin, all tired of inaction, all clamoring for the war to be ended by a vigorous campaign, we running our chances of being whipped by the enemy, instead of waiting until next spring, and then being forced by bankruptcy to abandon our work. The way we are scattered in this country now the enemy can take 1,000 or 2,000 of us just any morning they may feel so disposed, and their not doing it lowers them wonderfully in my opinion. There are about 6,000 of us stationed at nine points along 75 miles of railroad, and there is no point that 4,000 men could not reach and attack, and take before assistance could be afforded. But the Rebels don’t show any more dash or spirit than we do, so we all rest perfectly easy in our weakness, confiding in their lack of vim, which we gauge by our own. A line drawn through Fulton, Miss., Warrenton, Ala. and thence to Rome, Ga. (at which last place we think the enemy are concentrating) will give you the route over which the enemy are now moving in considerable bodies, while whole brigades of their numerous cavalry pass nearer us, through Newburg, Moulton and Somerville, Ala. ‘Twould be so easy for them to detach a division and send it up to this line of road. Buell, with a very respectable force, is near Stephenson in northeastern Alabama moving so slowly that no one can tell in which direction. I wish they’d give Grant the full control of the strings. He would be sure to have somebody whipped, and I’d rather ‘twould be us than live much longer in this inactivity. People are most outrageously secesh here, generally, although there are said to be some settlements very Union. I saw two men yesterday who were raising the 1st Union Alabama Regiment. They have two full companies they say, but I’ll never believe it until I see the men in blue jackets. This is the most beautiful valley that I ever saw. It lies between the Tennessee river and a spur of the Cumberland mountains, which are craggy and rough, and rocky enough to disgust an Illinoisan after a very short ride over and among them. Howwever, they form a beautiful background for the valley, and are very valuable in their hiding places for the guerrillas who infest them, and sally out every night to maraud, interfere with our management of this railroad and to impress what few able bodied butternuts there are left in their homes. They either cut the wires or tear up a little road track for us every night. We have guards too strong for them at every culvert, bridge and trestle. This country was entirely out of gold and silver until our cotton buyers came in with the army, and every man of money had his little 5-cent, 50-cent, etc., notes of his own for change. Mitchell’s men counterfeited some of them and passed thousands of dollars of their bogus on the natives. I send you a couple of samples of what is known here as Mitchell money. The man I got these of had been fooled with over $20 of it. The boys couldn’t get the proper vignette so, as you will observe, they used advertising cuts of cabinet warehouses and restaurants. Many of our men have passed Mustang Liniment advertisements on the people, and anything of the kind is eagerly taken if you tell them it is their money; of course I refer to the poor country people, who, if they can read, don’t show their learning. This man with $20, like that which I send you, is a sharp, shrewd-looking hotel keeper. His house is larger than the “Peoria House.” General Morgan, who is in command of the infantry here, is a fine man, but lacks vim or something else. He isn’t at all positive or energetic. The weather still continues delightful. I have’nt used any linen clothing yet, although I believe there is some in my trunk. We ride down to the Tennessee river every night and bathe, and ’tis so delightful. I don’t believe anybody ever had a nicer place than I have, or less reason to be dissatisfied. Well, I do enjoy it; but don’t think I’d worry one minute if sent back to my regiment or further back to my old place in the 8th. I believe I have the happy faculty of accommodating myself to cirumstances, and of grumbling at and enjoying everything as it comes. I am still desperately “out” with these secesh, but borrow books from them to while away my spare time. These people, safe in the knowledge of our conciliatory principles, talk their seceshism as boldly as they do in Richmond. Many of our officers have given up all hope of our conquering them and really wish for peace. For myself, I know its a huge thing we have on our hands, but I believe I’d rather see the whole country red with blood, and ruined together than have this 7,000,000 of invalids (these Southerners are nothing else as a people) conquer, or successfully resist the power of the North. I hate them now, as they hate us. I have no idea that we’ll ever be one nation, even if we conquer their armies. The feeling is too deep on both sides, for anything but extermination of one or the other of the two parties to cure, and of the two, think the world and civilization will lose the least by losing the South and slavery.

Sunday, 3d—When the sick call was made this morning, I went to see the doctor for the first time. I was threatened with fever and the doctor gave me three “Blue Mass” pills and marked me off duty for three days.

August 3, 1862. Sunday. — . . . Was glad to be able to release Mr. Landcraft and Mrs. Roberts. This arrest was a foolish business.

3rd. Sunday. Started again at 4 A. M. Marched 14 miles in sight of Fort Scott. Then turned back two miles on account of the scarcity of water. Encamped along a little vale where were little puddles of water. Got into camp a little after noon. Slept some. Got wood for a fire. Helped eat some oysters and sardines. Supper at 5 P. M. Mail came bringing a letter from Minnie. Wrote home. Sent a letter to Fannie. Saw some new acts relating to the formation of regiments under the new law. All Batt. staffs to be mustered out. One more 2nd Lt. to a company. A good berth for some of the staff. Warm day, not much like Sunday.

Sunday, August 3.—Got permission to go on to the regiment. Started at 6 A. M. Arrived at 6 p. M.

(Note: picture is of an unidentified Confederate soldier.)

AUGUST 3D.—There is a rumor that McClellan is “stealing away” from his new base! and Burnside has gone up the Rappahannock to co-operate with Pope in his “march to Richmond.”