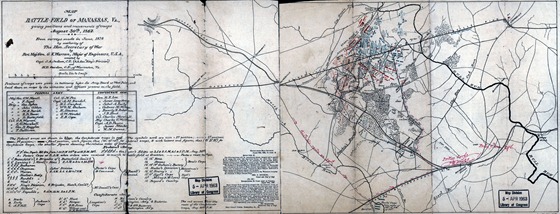

August 31, Sunday. For the last two or three days there has been fighting at the front and army movements of interest. McClellan with most of his army arrived at Alexandria a week or more ago, but inertness, inactivity, and sluggishness seem to prevail. The army officers do not engage in this move of the War Department with zeal. Some of the troops have gone forward to join Pope, who has been beyond Manassas, where he has encountered Stonewall Jackson and the Rebel forces for the last three days in a severe struggle. The energy and rapid movements of the Rebels are in such striking contrast to those of our own officers that I shall not be seriously surprised at any sudden dash from them. The War Department — Stanton and Halleck—are alarmed. By request, and in anticipation of the worst, though not expecting it, I have ordered Wilkes and a force of fourteen gunboats, including the five light-draft asked for by Burnside, to come round into the Potomac, and have put W. in command of the flotilla here, disbanding the flotilla on the James.

Yesterday, Saturday, P.M., when about leaving the Department, Chase called on me with a protest addressed to the President, signed by himself and Stanton, against continuing McClellan in command and demanding his immediate dismissal. Certain grave offenses were enumerated. Chase said that Smith had seen and would sign it in turn, but as my name preceded his in order, he desired mine to appear in its place. I told him I was not prepared to sign the document; that I preferred a different method of meeting the question; that if asked by the President, and even if not asked, I was prepared to express my opinion, which, as he knew, had long been averse to McClellan’s dilatory course, and was much aggravated from what I had recently learned at the War Department; that I did not choose to denounce McC. for incapacity, or to pronounce him a traitor, as declared in this paper, but I would say, and perhaps it was my duty to say, that I believed his removal from command was demanded by public sentiment and the best interest of the country.

Chase said that was not sufficient, that the time had arrived when the Cabinet must act with energy and promptitude, for either the Government or McClellan must go down. He then proceeded to expose certain acts, some of which were partially known to me, and others, more startling, which were new to me. I said to C. that he and Stanton were familiar with facts of which I was ignorant, and there might therefore be propriety in their stating what they knew, though in a different way, — facts which I could not indorse because I had no knowledge of them. I proposed as a preferable course that there should be a general consultation with the President. He objected to this until the document was signed, which, he said, should be done at once.

This method of getting signatures without an interchange of views with those who are associated in council was repugnant to my ideas of duty and right. When I asked if the Attorney-General and Postmaster-General had seen the paper or been consulted, he replied not yet, their turn had not come. I informed C. that I should desire to advise with them in so important a matter; that I was disinclined to sign the paper; did not like the proceeding; that I could not, though I wished McClellan removed after what I had heard, and should have no hesitation in saying so at the proper time and place and in what I considered the right way. While we were talking, Blair came in. Chase was alarmed, for the paper was in my hand and he evidently feared I should address B. on the subject. This, after witnessing his agitation, I could not do without his consent. Blair remained but a few moments; did not even take a seat. After he left, I asked Chase if we should not call him back and consult him. C. said in great haste, “No, not now; it is best he should for the present know nothing of it.” I took a different view; said that there was no one of the Cabinet whom I would sooner consult on this subject, that I thought Blair’s opinion, especially on military matters, he having had a military education, very correct. Chase said this was not the time to bring him in. After Chase left me, he returned to make a special request that I would make no allusion concerning the paper to Blair or any one else.

Met, by invitation, a few friends last evening at Baron Gerolt’s.[1] My call was early, and, feeling anxious concerning affairs in front, I soon excused myself to go to the War Department for tidings. Found Stanton and Caleb Smith alone in the Secretary’s room. The conduct of McClellan was soon taken up; it had, I inferred, been under discussion before I came in.

Stanton began with a statement of his entrance into the Cabinet in January last, when he found everything in confusion, with unpaid bills on his table to the amount of over $20,000,000 against the Department; his inability, then or since, to procure any satisfactory information from McClellan, who had no plan nor any system. Said this vague, indefinite uncertainty was oppressive; that near the close of January he pressed this subject on the President, who issued the order to him and myself for an advance on the 22d of February. McClellan began at once to interpose objections, yet did nothing, but talked always vaguely and indefinitely and of various matters except those immediately in hand. The President insisted on, and ordered, a forward movement. Then McClellan stated he intended a demonstration on the upper waters of the Potomac, and boats for a bridge were prepared with great labor and expense. He went up there and telegraphed back that two or three officers—his favorites — had done admirably in preparing the bridge and he wished them to be brevetted. The whole thing was absurd, eventuated in nothing, and he was ordered back.

The President then commanded that the army should proceed to Richmond. McClellan delayed, hesitated, said he must go by way of the Peninsula, would take transports at Annapolis. In order that he should have no excuse, but without any faith in his plan, Stanton said he ordered transports and supplies to Annapolis. The President, in the mean time, urged and pressed a forward movement towards Manassas. Spoke of its results, — the wooden guns, the evacuation by the Rebels, who fled before the General came, and he did not pursue them but came back to Washington. The transports were then ordered round to the Potomac, where the troops were shipped to Fortress Monroe. The plans, the number of troops to proceed, the number that was to remain, Stanton recounted. These arrangements were somewhat deranged by the sudden raid of Jackson towards Winchester, which withdrew Banks from Manassas, leaving no force between Washington and the Rebel army at Gordonsville. He then ordered McDowell and his division, also Franklin’s command, to remain, to the great grief of McDowell, who believed glory and fighting were all to be with the grand army. McClellan had made the withholding of this necessary force to protect the seat of government his excuse for not being more rapid and effective; was constantly complaining. The President wrote him how, by his arrangement, only 18,000 troops, remnants and odd parcels, were left to protect the Capital. Still McClellan was complaining and underrating his forces; said he had but 96,000, when his own returns showed he had 123,000. But, to stop his complaints and drive him forward, the President finally, on the 10th of June, sent him McCall and his division, with which he promised to proceed at once to Richmond, but did not, lingered along until finally attacked. McClellan’s excuse for going by way of the Peninsula was that he might have good roads and dry ground, but his complaints were unceasing, after he got there, of bad roads, water, and swamps.

When finally ordered, after his blunders and reverses, to withdraw from James River, he delayed obeying the order for thirteen days, and never did comply until General Burnside was sent to supersede him if he did not move.

Since his arrival at Alexandria, Stanton says, only delay and embarrassment had governed him. General Halleck had, among other things, ordered General Franklin’s division to go forward promptly to support Pope at Manassas. When Franklin got as far as Annandale he was stopped by McClellan, against orders from Headquarters. McClellan’s excuse was he thought Franklin might be in danger if he proceeded farther. For twenty-four hours that large force remained stationary, hearing the whole time the guns of the battle that was raging in front. In consequence of this delay by command of McClellan, against specific orders, he apprehended our army would be compelled to fall back.

Smith left whilst we were conversing after this detailed narrative, and Stanton, dropping his voice, though no one was present, said he understood from Chase that I declined to sign the protest which he had drawn up against McClellan’s continuance in command, and asked if I did not think we ought to get rid of him. I told him I might not differ with him on that point, especially after what I had heard in addition to what I had previously known, but that I disliked the method and manner of proceeding, that it appeared to me an unwise and injudicious proceeding, and was discourteous and disrespectful to the President, were there nothing else. Stanton said, with some excitement, he knew of no particular obligations he was under to the President, who had called him to a difficult position and imposed upon him labors and responsibilities which no man could carry, and which were greatly increased by fastening upon him a commander who was constantly striving to embarrass him in his administration of the Department. He could not and would not submit to a continuance of this state of things. I admitted they were bad, severe on him, and he could and had stated his case strongly, but I could not from facts within my own knowledge indorse them, nor did I like the manner in which it was proposed to bring about a dismissal. He said among other things General Pope telegraphed to McClellan for supplies; the latter informed P. they were at Alexandria, and if P. would send an escort he could have them. A general fighting, on the field of battle, to send to a general in the rear and in repose an escort!

Watson, Assistant Secretary of War, repeated to me this last fact this morning, and reaffirmed others. He informs me that my course on a certain occasion had offended McClellan and was not approved by others; but that both the President and Stanton had since, and now, in their private conversation, admitted I was right, and that my letter in answer to a curt and improper demand of McClellan last spring was proper and correct. Watson says he always told the President and Stanton I was right, and he complimented me on several subjects, which, though gratifying, others can speak of and judge better than myself.

We hear, this Sunday morning, that our army has fallen back to Centreville.[2] Pope writes in pretty good spirits that we have lost no guns, etc. The Rebels were largely reinforced, while our troops, detained at Annandale by McClellan’s orders, did not arrive to support our wearied and exhausted men. McClellan telegraphs that he hears “Pope is badly cut up.” Schenck, who had a wound in his arm, left the battle-field, bringing with him for company an Ohio captain. Both arrived safe at Willard’s. They met McCall on the other side of Centreville and Sumner on this side. Late! late!

Up to this hour, 1 P.M., Sunday, no specific intelligence beyond the general facts above stated. There is considerable uneasiness in this city, which is mere panic. I see no cause for alarm. It is impossible to feel otherwise than sorrowful and sad over the waste of life and treasure and energies of the nation, the misplaced confidence in certain men, the errors of some, perhaps the crimes of others, who have been trusted. But my faith in present security and of ultimate success is unshaken. We need better generals but can have no better army. There is much latent disloyal feeling in Washington which should be expelled. And oh, there is great want of capacity and will among our military leaders.

I hear that all the churches not heretofore seized are now taken for hospital purposes; private dwellings are taken to be thus used, among others my next neighbor Corcoran’s[3] fine house and grounds. There is malice in this. I told General Halleck it was vandalism. He admitted it would be wrong. Halleck walked over with me from the War Department as far as my house, and is, I perceive, quite alarmed for the safety of the city; says that we overrate our own strength and underestimate the Rebels’ — a fatal error in Halleck. This has been the talk of McClellan, which none of us have believed.

[1] Prussian Minister.

[2] After the defeat in the Second Battle of Bull Run.

[3] William W. Corcoran, the banker, who among other public benefactions gave the city of Washington the art gallery which bears his name.