Note: This letter—a document written in 1862—includes terms and topics that may be offensive to many today. No attempt will be made to censor or edit 19th century material to today’s standards.

On Steamer Henry Clay, off New Madrid, Mo.,

April 16, 1862.

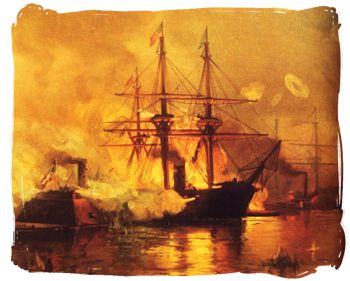

I finished my last in a great hurry, helped strike and load our tents and equipage and started for the levee, confident that we would be off for Memphis, Orleans and intermediate landings, before the world would gain 12 hours at farthest in age. That day over 30 steamers arrived, received their loads of soldiers and departed, all down stream, preceded by six or eight gunboats and 16 mortarboats. Word came at nightfall that there were not enough boats for all and the cavalry would have to wait the morrow and more transports. We lay on the river banks that night, and the next day all the cavalry got off except our brigade of two regiments. Another night on the banks without tents, managed to get transportation for for two battalions, one from each regiment. They started down yesterday at about 10 a.m. and more boats coming we loaded two more battalions, but at 9 p.m. a dispatch boat came up with orders for us to stop loading and await further orders. The same boat turned back all the cavalry of our brigade that had started and landed them at Tiptonsville; we are at 6 this p.m. lying around loose on the bank here awaiting orders. That boat brought up word that our fleet was at Fort Pillow, and the Rebels were going to make a stand there, but that nothing had occurred when she left but some gunboats skirmishing. What the devil we are going to do is more than three men like me can guess. It’s awful confounded dull here. Nothing even half interesting. Saw a cuss, trying to drown himself yesterday, and saw a fellow’s leg taken off last night. These are better than no show at all, but still there’s not much fun about either case. I’m bored considerably by some of my Canton friends wanting me to help them get their niggers out of camp. Now, I don’t care a damn for the darkies, and know that they are better off with their masters 50 times over than with us, but of course you know I couldn’t help to send a runaway nigger back. I’m blamed if I could. I honestly believe that this army has taken 500 niggers away with them. Many men have lost from 15 to 30 each. The owners were pretty well contented while the army stayed here, for all the generals assured them that when we left the negroes would not be allowed to go with us, and they could easily get them back; but they have found out that was a “gull” and they are some bitter on us now. There will be two Indiana regiments left here to guard the country from Island 10 to Tiptonsville, and if you don’t hear of some fun from this quarter after the army all leaves but them, I’m mistaken. They’ll have their hands full if not fuller. We have not been paid yet but probably will be this week. I tell you I can spend money faster here than anywhere I ever was in my life, but of course I don’t do it. Am trying to save up for rainy weather, and the time, if it should come, when I’ll have only one leg to go on or one arm to work with. That Pittseburg battle was one awful affair, but it don’t hurt us any. Grant will whip them the next time completely. Poor John Wallace is gone. He was a much better boy than he had credit for being. We all liked him in the old mess very much. Ike Simonson, of same company, I notice was wounded. He was also in my mess; was from Farmington. There are no rumors in camp to-day. Yesterday it was reported and believed that the Monitor had sunk the Merrimac, that Yorktown was taken, and that another big fight had taken place at Corinth and we held the town. That was very bully but it lacks confirmation. Think it will for sometime yet, but Pope says we’ll come out all right through all three of those trials. It’s just what’s wanted to nip this rebellion up root and all. That’s a rather dubious victory up to date, that Pittsburg affair, but guess it’s all right.