You will prepare your ship for service in the Mississippi River in the following manner:

Send down the top-gallant masts. Rig in the flying jib-boom, and land all the spars and rigging, except what are necessary for the three topsails, foresail, jib, and spanker. Trice up to the topmast stays or land the whiskers, and bring all the rigging into the bowsprit, so that there shall be nothing in the range of the direct fire ahead.

Make arrangements, if possible, to mount one or two guns on the poop and top-gallant forecastle; in other words, be prepared to use as many guns as possible ahead and astern, to protect yourself against the enemy’s gunboats and batteries, bearing in mind that you will always have to ride head to the current, and can only avail yourself of the sheer of the helm to point a broadside gun more than three points forward of the beam.

Have a kedge in the mizzen chains (or any convenient place) on the quarter, with a hawser bent and leading through in the stern chock, ready for any emergency; also grapnels in the boats, ready to hook on to, and to tow off, fire-ships. Trim your vessel a few inches by the head, so that if she touches the bottom she will not swing head down the river. Put your boat howitzers in the fore-maintops, on the boat carriages, and secure them for firing abeam, etc. Should any injury occur to the machinery of the ship, making it necessary to drop down the river, you will back and fill down under sail, or you can drop your anchor and drift down, but in no case attempt to turn the ship’s head down stream. You will have a spare hawser ready, and when ordered to take in tow your next astern do so, keeping the hawser slack so long as the ship can maintain her own position, having a care not to foul the propeller.

No vessel must withdraw from battle, under any circumstances, without the consent of the flag-officer. You will see that force and other pumps and engine hose are in good order, and men stationed by them, and your men will be drilled to the extinguishing of fire.

Have light Jacob-ladders made to throw over the side for the use of the carpenters in stopping shot-holes, who are to be supplied with pieces of inch board lined with felt and ordinary nails, and see that the ports are marked in accordance with the ‘ordnance instructions’ on the berth deck, to show the locality of the shot-hole.

Have many tubs of water about the decks, both for the purpose of extinguishing fire and for drinking. Have a heavy kedge in the port main-chains, and a whip on the main yard, ready to run it up and let fall on the deck of any vessel you may run alongside of, in order to secure her for boarding.

You will be careful to have lanyards on the lever of the screw so as to secure the gun at the proper elevation, and prevent it from running down at each fire. I wish you to understand that the day is at hand when you will be called upon to meet the enemy in the worst form for our profession. You must be prepared to execute all those duties to which you have been so long trained in the Navy without having the opportunity of practicing. I expect every vessel’s crew to be well exercised at their guns, because it is required by the regulations of the service, and it is usually the first object of our attention; but they must be equally well trained for stopping shot-holes and extinguishing fire. Hot and cold shot will, no doubt, be freely dealt to us, and there must be stout hearts and quick hands to extinguish the one and stop the holes of the other.

I shall expect the most prompt attention to signals and verbal orders, either from myself or the Captain of the fleet, who, it will be understood, in all cases acts by my authority.

D. G. Farragut.

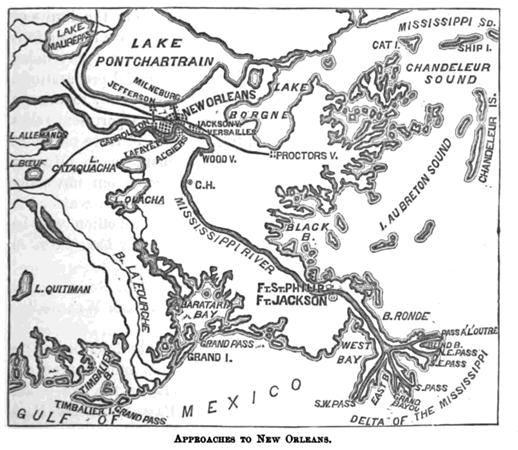

It is reported that nineteen feet of water can be carried over the bar. If this be true, the frigate Mississippi can be got over without much difficulty. The Colorado draws about twenty-two feet; she lightens one inch to twenty-four tons; her keel is about two feet deep. The frigate Wabash, when in New York in 1858, drew, without her spar-deck guns, stores, water casks, tanks, and coal (excepting thirty tons), aft twenty feet four inches, forward sixteen feet, or on an even keel eighteen feet four inches. This would indicate a very easy passage for this noble vessel, and, if it be possible to get these two steamers over, and perhaps a sailing vessel also, you will take care to use every exertion to do so. The powerful tugs in the bomb flotilla will afford the necessary pulling power. The tops of these large steamers are from thirty to fifty feet above the fort, and command the parapets and interior completely with howitzers and musketry. The Wachusett at Boston; the Oneida, Richmond, Varuna, and Dakota at New York; and the Iroquois from the West Indies, are ordered to report to you with all practicable dispatch, and every gunboat which can be got ready in time will have the same orders. All of the bomb-vessels have sailed, and the steamers to accompany them are being prepared with great dispatch. It is believed the last will be off by the 16th instant.

It is reported that nineteen feet of water can be carried over the bar. If this be true, the frigate Mississippi can be got over without much difficulty. The Colorado draws about twenty-two feet; she lightens one inch to twenty-four tons; her keel is about two feet deep. The frigate Wabash, when in New York in 1858, drew, without her spar-deck guns, stores, water casks, tanks, and coal (excepting thirty tons), aft twenty feet four inches, forward sixteen feet, or on an even keel eighteen feet four inches. This would indicate a very easy passage for this noble vessel, and, if it be possible to get these two steamers over, and perhaps a sailing vessel also, you will take care to use every exertion to do so. The powerful tugs in the bomb flotilla will afford the necessary pulling power. The tops of these large steamers are from thirty to fifty feet above the fort, and command the parapets and interior completely with howitzers and musketry. The Wachusett at Boston; the Oneida, Richmond, Varuna, and Dakota at New York; and the Iroquois from the West Indies, are ordered to report to you with all practicable dispatch, and every gunboat which can be got ready in time will have the same orders. All of the bomb-vessels have sailed, and the steamers to accompany them are being prepared with great dispatch. It is believed the last will be off by the 16th instant.