April 30.—I saw General Price when he rode to camp. I think he is one of the finest looking men on horseback that I have ever seen. I have a picture of Lord Raglan in the same position, and I think that he and General P. are the image of each other. I showed the picture to some of the doctors, and they agreed with me. General P. is in bad health, but could not be induced to stay longer with us, as his abode is with his soldiers in the camp, where he shares their sorrows and joys. It is this that has so endeared him to them. Missouri may well be proud of her gallant son.

The hospital is nicely fixed up; every thing is as neat and clean as can be in this place.

Mrs. Glassburn has received a great many wines and other delicacies from the good people of Natchez. I believe they have sent every thing—furniture as well as edibles. We have dishes in which to feed the men, which is a great improvement. The food is much better cooked. We have negroes for cooks, a good baker, a nice dining-room, and eat like civilized people. If we only had milk for the patients, we might do very well.

There is a young man here taking care of his brother, who is shot through the jaw. The brother procures milk from one of the farm-houses near, and had it not been for this I believe the sick man would have died of starvation. We have a few more such, and they have to be fed like children. One young man, to whom one of the ladies devotes her whole time, has had his jaw-bone taken out. We have a quantity of arrow-root, and I was told that it was useless to prepare it, as the men would not touch it. I thought that I would try them, and now use gallons of it daily. I make it quite thin, and sometimes beat up a few eggs and stir in while hot; then season with preserves of any kind—those that are a little acid are the best—and let stand until it becomes cold. This makes a very pleasant and nourishing drink; it is good in quite a number of diseases; will ease a cough; and is especially beneficial in cases of pneumonia. With good wine, instead of the preserves, it is also excellent; I have not had one man to refuse it, but I do not tell them of what it is made.

Our army is being reinforced from all quarters. The cars are coming and going constantly, and the noise is deafening. It is a blessing that our men are not nervous, or the noise would kill them. We are strongly fortifying this place. I hope we will soon gain a victory; but our forces can not tempt the Yankees to fight.

We are told by Dr. Smith to do what is necessary for the prisoners, but talk as little as possible to them. The captain from Cincinnati is still here; a very sick lieutenant is in the same room. I believe he is one of the captain’s officers. I have to attend him. A few mornings since, when I was visiting him, the captain stated that there was good news in the papers. (He is allowed to read all the southern papers.) I asked what it was. He answered that a proposition had been made for the exchange of prisoners; and that it came from our side. I remarked that all humane proposals came from our side and that I did not think that his would be magnanimous enough to accept it. He said he hoped they would, so that he could see his home once more. I pray so too, as I know that our men who are prisoners have been enduring extreme hardship.

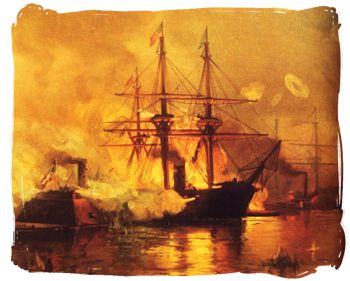

Every one is still down-hearted about New Orleans, as its fall has divided the Confederacy by opening the Upper Mississippi River to the enemy. All praise the spirited answer given by the mayor when ordered to surrender the city. He said that the citizens of New Orleans yielded to physical force alone, and that they still maintained their allegiance to the Confederate States; and upon refusal to pull down the state flag from the city hall, Commodore Farragut threatened to bombard the city. The mayor replied, the people of New Orleans would not degrade themselves by the humiliating act of lowering their own flag, and that there was no possible way for the women and children to leave; so he would have to do his worst. We can not but admire such spirited behavior; but it is nothing but what I expected from the proud Louisianans. Indeed, I had no idea that they would give up their much-prized city as easily as they did, but thought that it would have to be taken street by street. When all is known, I trust that the people will not be blamed. A number of Louisiana troops are here, who are much enraged about it. General Lovell, who was in command, is severely censured, but I trust he is not in fault.

We are still busy; wounded men are constantly brought in. To-day, two men had each a leg amputated. It is supposed that both will die.

General Van Dorn, with a number of his troops, has just arrived.