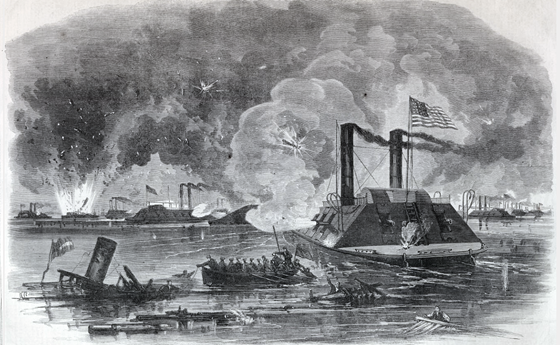

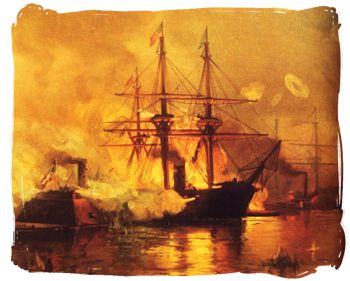

Naval Combat off Fort Wright in the Mississippi River, May 8, 1862, (from Harper’s Weekly, May 31, 1862.)

[update to post, 8-27-2013: The content of this post is from the May 31, 1862 issue of Harper’s Weekly. News articles of the day were often inaccurate and slanted in favor of “their” side of the conflict. Please see the comment by Mark Morss after the end of this post for more info on this naval action.]

ON page 341 we illustrate the combat which took place on the Mississippi River, off Fort Wright, on 8th May. The correspondent of the Herald thus describes the scene:

The morning was one of the finest of the season, though, as is very common in this region, before sunrise a dull haze spread over the water, making it difficult to see at any great distance away. Just at daylight the mortar-boats were towed down to their positions, ready for their day’s work. This morning the gun-boat Cincinnati was sent down with them as a precautionary measure. The latter dropped anchor just abreast of the mortars, and but a short distance out in the stream. Scarcely had she swung around and become settled in her position when the look-out gave the signal, “Steamer astern!” Sure enough, by peering through the masts, a low, dark object was discovered, bearing a strong resemblance to a steam craft of some kind. It was subsequently ascertained to be the rebel ram Louisiana. All hands were beat to quarters, and the gun-boat was cleared for action immediately. The promptness of the response of the men in putting the boat in fighting shape was most remarkable. The anchor was up almost simultaneously with the issue of the order, the decks were cleared of all rubbish and every thing in the shape of obstruction, and every man was standing at his gun. By this time the rebel craft had approached near enough to be readily recognized, and just as the early sun was dispelling the haze the Cincinnati swung around and welcomed the visitor with a full broadside. As the sound of the report and its tremendous reverberations ran along the shore and reached the ears of those manning the other boats of our fleet, there was one general shout of gladness as every officer and man sprang to his feet and prepared for duty. With the report came also reinforcements to the rebel boat. Three in number, they came quickly around the point, and prepared to grapple with the spunky Yankee. The Louisiana ram carried two heavy rifled pieces, both of which, together with the guns of her consorts, were soon bearing upon the Cincinnati, and throwing in shot after shot in rapid succession. But against them all the Cincinnati boldly held her position, her sloping iron sides repelling their heaviest missiles as though they were but paper balls. This unequal contest lasted for full twenty minutes, during all of which time the rebel gun-boats were kept in check by the Cincinnati alone. The ram, however, ran up close to the Union boat, and manifested a disposition to run her down.

Just at this juncture the other iron-clad boats of our fleet came to the rescue—the Benton (flag-ship), Carondolet, Pittsburg, Cairo, and St. Louis—and relieved the Cincinnati of the necessity of giving any further immediate attention to the rebel gun-boats, thus enabling her to close in with the ram alone.

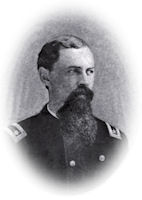

The Louisiana came along up, under full steam, until nearly upon the Cincinnati, when the latter put her head about and avoided the well-intended blow. Her crew were on deck, armed with cutlasses, boarding pikes, and carbines, fully prepared for a close hand to hand encounter. The ram, foiled in her first attempt, withdrew a short distance, and again turned upon the Union boat. This time she got her sharp bow full in upon the heavy iron sides of the Cincinnati; but her headway was not sufficient to cause any very serious damage. Before she could get away, however, Captain Stembel, commanding the Cincinnati, rushed upon the hurricane deck, and, seizing a pistol, shot the rebel pilot, killing him instantly. ‘rhe rebel crew retaliated, when a musket-ball entered the gallant Captain’s right shoulder, high up, nearly to the neck, and passed quite through. The wound was a troublesome and painful one, but not sufficiently serious to detain the Captain from his post longer than to have it dressed. In the mean time the ram had prepared for another assault, and this time evidently with the intention of boarding her antagonist. She came up under full headway, and with her steam batteries ready for immediate us. Just as she struck the Cincinnati, however, her steam apparatus collapsed, scalding a large number of her crew. Captain Stembel was also prepared with his steam battery to add to their discomfiture, and almost simultaneously with the explosion a dense volume of scalding water and steam came pouring upon the rebel crew front the deck of the gun-boat. This was too much for them to withstand, and those who were left uninjured and alive managed to get their craft away beyond the reach of further injury.

The casualties on the Cincinnati were very slight. Her gallant commander was wounded, as mentioned above. Her first master received a flesh wound in his thigh, and two seamen were slightly wounded.

As the ram drew away the iron-clad gun-boat Mallory appeared as a new antagonist. This is one of the new boats of which so much boast has been made by the rebels. She had just been completed at Memphis, and on this occasion made her first public appearance. She was a powerful craft carrying ten or twelve guns, and sheathed with heavy boiler iron over heavy timber bulkheads stuffed with cotton.

Her first manoeuvre was an attempt to run the Cincinnati down by butting against her. This was baffled by the dextrous handling of the latter boat, though several times attempted. Then she hauled alongside and opened a close fire, but received rather more than she gave. The heavy Dahlgrens of the Union craft were too much for her, and again she resorted to the battering process. Just as she was preparing to strike, with all the power of momentum acquired by a quarter of a mile’s running, the St. Louis—Union iron-clad boat—bore down upon her, and, striking her fairly amidships, nearly cut her in two. She sank almost immediately, and within two hundred feet of the vessel she was attempting herself to run down. The most of her crew must have perished, though a number were picked up by our boats. She is a total loss, having sunk in deep water.

Comparatively few of our shots were wasted. They were all admirably directed and did wonderful execution, as the condition of the rebel boats fully shows. But their execution was better apparent in the explosion and total destruction of two of the most powerful of the rebel gun-boats. The names of these I have not yet been able to ascertain.

Their destruction occurred nearly at the same time and when the engagement was at its height. Above the loud din of the cannon could occasionally be heard the shouts and cheers of the loyal crews as they discerned one and another evidence of their sure approaching final triumph. The whole scene was shut out from view by the dense volumes of smoke that settled over the fleet, the result of the heavy firing. There was something grand and inspiring in all this, even to one outside, who could only hear the din and see the smoke. But suddenly there came a report louder than, and distinguishable above, all the others; and accompanying it could be seen a volume of white smoke rolling and surging above the other smoke, and bearing on its rolling waves black masses and fragments, which again quickly disappeared. What was it? The smoke lifted and revealed the cause. A well-directed shell had struck in the magazine of a rebel boat, causing an instantaneous explosion of the shell, magazine, and boilers. The boat was blown to atoms, and her crew perished with her. It was a fearful casualty, and one that is well calculated to awaken the deepest sympathy and pity for the poor unfortunates thus suddenly sent into eternity; but “it is the fortune of war,” and the din goes on, and more destruction is attempted.

During the heat of the engagement one of the rebel rams—supposed to be the Manassas—singled out the Benton as its prey. The latter at first scarcely deigned to notice so insignificant an adversary, but continued to devote her time to the heavier gun-boats. Her powerful guns were all at work. She was kept in constant motion, first discharging her four bow guns, then hauling about and letting go her broadside of five pieces, and again bringing her stern pieces in range, and so on until the round was completed. All this time the ram danced about, endeavoring to get a chance to give her is good butt. At last the opportunity arrived, and with a powerful head of steam on the ram flew to her work. She struck the flag-ship fairly, right amidships, but was doubtless much amazed, on withdrawing, to find that she had suffered more damage herself than she had inflicted. Her nose was badly jammed, while the solid iron sides of the Benton showed no signs whatever of the assault. It was a signal discomfiture, rendered doubly annoying by the reception of a round of grape-shot from her antagonist that compelled her to get out of the way with the least possible delay.

By this time it was apparent that the enemy must withdraw quickly or be wholly destroyed. They had entered the contest with five gun-boats and three rams—eight in all. Three of their gun-boats were totally destroyed. The remaining two, as also the rams, were riddled through and through, and all appeared to be leaking badly. On the contrary, our boats, excepting the Cincinnati, appeared wholly uninjured, and were in condition to continue the action all day if necessary. Under these circumstances the rebels had no alternative, and at twenty minutes past seven—just one hour and twenty minutes after the commencement of the battle—the last of them disappeared around Craighead Point, the heavy cannonading ceased, the smoke cleared away, our boats returned to their moorings, and the battle was ended.

London, May 8, 1862

London, May 8, 1862