Friday, 8th.—I. L. got fifteen days’ furlough; gone to Social Circle. Papers filled with news of Confederates invading Maryland and near Washington City. Marching and marching and falling back, until, [next entry July 22, 1864]

Tuesday, July 8, 2014

8th. Barber was sick so Bob and Thede got dinner. Very warm day. Did very little. Read some.

Headquarters 56th Mass. Vols.,

Near Petersburg, July 8, 1864.

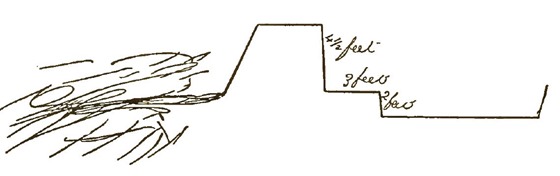

Dear Hannah, — . . . You ask me what rifle-pits are. A rifle-pit proper is a small hole dug for sharpshooters or pickets. It is detached and separate from any other pit, and holds from one to three men. The term is commonly used, however, as synonymous with breastworks. I give you a profile view of one properly constructed. When the men fire, they stand on the place marked “3 feet.” That is called the “banquette.” When they are not in action, they go down 2 feet lower, and are pretty well protected. When we are at all exposed to a flank fire, traverses are built. They are mounds of earth running at right angles with the main rifle-pit. They have to be built quite high and thick in order to resist artillery. Where I was the last time I was at the front, we would have to trust to our legs and a kind Providence to protect us whenever we went anywhere from the pits. The enemy would shoot at us regularly. In most cases narrow ditches are dug, with the earth from the ditch thrown up towards the enemy, leading to the rear. The men can walk in these ditches with comparative safety.

Yesterday as our regiment was moved to the second line, I went out on a travelling expedition. I called on General Barlow first. He had just received the notice of ——’s dismissal from the service. It seems he asked the hospital steward to give him something to make him sick. It is too bad, especially as his brothers have done well. He had a great deal better have been killed. From General Barlow’s I went to General Hayes’s, my old colonel. He commands the brigade of Regulars in the Fifth Corps. I then went to the 10th Massachusetts, but could see no one that I knew. I went to the Second Corps hospital and found John Perry, and had a very pleasant time. John Perry will probably go home with the 10th. Their time is out to-day, and fifty of them go home. We were moved into the second line last evening in anticipation of an attack from the enemy, which did not come off.

I saw Frank Weld last evening and gave him your message. Torn Sherwin was with him. . . .

Headquarters 56th Mass. Vols.,

Near Petersburg, Va., July 8, 1864.

Dear Father, — I spend every morning now at division headquarters, where the court-martial, of which I am President, meets. We usually have a session of three hours every day. We are still in the front line of rifle-pits, but are to be relieved, I think, to-night. We have to keep very close to our works here, as the enemy have a rifle-pit on our right, which completely enfilades our line. We have to have traverses every 20 feet to cover the men. The men are protected from a front fire by a deep ditch, deep enough to cover them completely when standing up. I will give you a profile view of it.

When the men have to fire, they get up on the ” banquette ” which exposes them only as far as their head and the upper part of the body is concerned. When loading they step back into the ditch, so that they are completely covered, when not actually firing. The officers’ quarters are just in rear of the ditch, where they have to dig holes and put up logs to cover themselves. A traverse runs at right angles with the rifle-pit from the “interior slope,” and protects the men from a flank fire. They are usually made of logs and dirt thrown up so as to form an embankment. A traverse naturally divides the rifle-pits into different sections, and in order to connect these different sections I have had a deep and narrow ditch dug parallel with the rifle-pit. From each section another narrow ditch runs out and connects with the one parallel to the pit. The men can now travel round in comparative safety. Before I came here, it was very dangerous indeed to go from one section to another.

It is pretty well decided, I think, that anything that is done here in front of Petersburg, will have to be done by our corps. We are nearer the enemy’s works than any other corps except the Eighteenth, and they cannot advance any nearer the city, as the position in their front is commanded by the enemy’s batteries on the other side of the Appomattox. In front of our division we can certainly do nothing. If we attempt to charge, we shall be cut to pieces. Our only hope lies in General Potter’s front. He is mining under a battery of the enemy, and as soon as the mine is completed, 10,000 pounds of powder are to be placed in it. As soon as it is exploded, the negro division is to charge. Our brigade is to be the next in order, followed by a brigade from Willcox’s division, and then Potter’s division.

I see by the papers that Ewell has gone up to Pennsylvania. I hope that his raid will have the effect to increase volunteering. We need more men here very much indeed.

General Franklin is at City Point, I hear. His corps is on the way to join us from New Orleans, and is expected here in about six days.

I received the knife which you sent me, and am very much obliged to you for sending it. It is just the sort of a knife that I wished for.

I asked Hannah to buy me a small wooden inkstand to carry in my pocket, and a gutta-percha penholder. Please have them sent to me by mail as soon as convenient.

Captain Lamb joined us this morning. He is from the 2d Heavy Artillery, and is a gentleman and a very nice fellow. I nominated him to be captain. He was formerly second lieutenant in Frankle’s regiment. He is a brother of Miss Rose Lamb, who lives on Somerset St., Boston.

I have nominated Captain Adams of my regiment to be major. As he is wounded and a prisoner, I don’t expect to see him for some time. Still, he is a brave officer and a gentleman, and I did not think it would be right to skip him.

I almost wish that the enemy would go up into Penn., and transfer the seat of war there. I think that it would have a beneficial effect on our people, and would make them realize the necessity of crushing the enemy in this campaign.

I wish you would ask Alice to write me. I have heard nothing from her for a long time. I had quite a pleasant letter from Hannah this morning, dated July 3. . . .

The enemy have not shelled us much in our present position. They have shelled the troops on both sides of us, but have let us alone so far. I don’t know how long they will continue to leave us free from bombs and such things.

The Sanitary Commission is doing a great deal of good in distributing fresh vegetables among the troops. It has saved them from a great deal of sickness. The dry weather, too, has been a godsend to our men. I don’t know what we should do if we had much rain. The men would die off like sheep, as they have to be in the trenches all the time. Fever would thin our ranks fearfully in case we had rainy weather of long continuance.

Love to all the family.

July 8. — Court began on case of Lieutenant Knickerbocker. Day very warm indeed. We were moved into the second line at night, being the second regiment from the right. Captain Lamb reported for duty. Had brisk firing on our right, which extended down the line, the enemy opening on us with artillery.

Friday, 8th—The weather is quite pleasant today. Wounded men are coming in from the front every day. Our men are strongly fortified in front of the rebel works, and within about a mile of the Chattahoochee river.

July 8th. A little firing; the shell did damage where they struck, but none came near our camp.

July 8—Engle, Riter and myself received boxes from New York to-day, but as Riter has gone to the other prison with the 400 we have made away with his box.

London, July 8, 1864

What do you say to the news you’ve been sending us for a week back? Grant repulsed. Sherman repulsed. Hunter repulsed and in retreat. Gold, 250. A devilish pretty list, portending, as I presume, the failure of the campaign. To read it has cost me much in the way of mental consumption, which you can figure to yourself if you like. And now what is to be the end? “Contemplate all this work of time.” We have failed, let us suppose! The financial difficulty, a Presidential election, and a disastrous campaign are three facts to be met. Not for us to meet, but for the nation, our own share being very limited. Ebbene! Dana’s idea a year ago of throwing off New England is, I suppose, no longer practicable. But what is practicable seems to be a summary ejection of us gentlemen from our places next November, and the arrival of the Democratic party in power, pledged to peace at any price. This is my interpretation of the news which now lies before us. . . .

Lucky is it for us that all Europe is now full of its own affairs. The fate of this Ministry seems to be pretty nearly decided, so far as Parliament can decide it, without an appeal to the people. The division takes place tonight and the excitement in society is tremendous. Every one who has an office, or whose family has an office, is in a state of funk at the idea of losing it, and every one who expects an office is brandishing the tomahawk with frightful yells over his trembling victim. As for the degree of principle involved, I have not yet succeeded in seeing it. The nation understands it in the same way, as a struggle by one set of incapable men to keep office, and by another set of ditto to gain it.

Society is almost silent among the hostile warriors. I breakfasted with Lord Houghton last Wednesday and what do you think was the subject of conversation? Bokhara and the inhabitants of central Asia. Some twenty prominent people discussed nothing but Bokhara, while all Europe and America are on the high road to the devil. And a delightful breakfast it was to me who am weary with long mental and concealed struggles for hope. I revelled in Tartaric steppes, and took a vivid interest in farthest Samarcand. . . .

London, July 8, 1864

Meanwhile our friends on this side are in the midst of a crisis. The failure of the Ministry to secure a settlement of the Danish question has been made the ground of a formal attack by the opposition with a view to a change of government. The debate has been going on with great vehemence ever since Monday, and it is to close tonight with a division on a motion of want of confidence. The most sanguine of the ministerial side do not now expect any majority strong enough to sustain them. They talk of two or four; but I should not wonder if it proved the other way. The result will be known in season for this steamer. The probability now is that Lord Palmerston will determine to take the sense of the country by dissolving the Parliament. This is most certainly the right course. For the present House is in no condition to uphold government of any kind. Should this prove to be the policy, the country will for the next two months go through the spasm of a vehemently contested election, almost exclusively on personal grounds. I cannot perceive that any issue has been raised on principle. If the Ministry have made mistakes in their foreign policy, they do not appear to have been such as to render a material variation from it likely, if the opposition should take their places. The dispute is all about words. Lord Russell has been rough and menacing in his tone. Admitting this to be just (and I am not prepared myself to say that he is the most soft-spoken of men), the only change demanded is a little more politeness. The benefit of this will enure to foreign countries, it is true; but I scarcely understand how it is likely to extend to events or acts. “Great Britain has no friends in the world,” people complain, who at the very same time indulge in a style of oratory towards foreign countries which goes clearly to show the reason why she has not any. If Great Britain indulges her fancy for abusing everybody it stands to reason that nobody will be grateful. The country however has no inclination on any side, as it would appear, to go further than to talk. Why then change the government, on a question of politeness? If Lord Russell has been brusque, let him amend his style and soften his manners, instead of giving place to another who will do no more.

The real difficulty is in the condition of the House of Commons itself, which furnishes no basis whatever on which a minister can do more than talk or write. If an appeal to the country should result in returning a working majority for any man or set of men, then would something substantial be gained. It is possible that Lord Palmerston’s personal popularity may secure this. He is the only really strong man in the public confidence left in England. But from what I gather, it is matter of serious doubt whether even he can do all that is needed. In the absence of any real issue, the reform bill has worked a state of the constituencies which gives no positive result to either side on a general election. If it should prove so on this occasion, then the last state of the patient will be worse than the first. . . .