Saturday, 22d—It is quite pleasant today. I went out with a team after a load of lumber for our company. We pulled down an old, vacant barn. No property is being burned and destroyed in this state, and only vacant buildings are torn down to get lumber with which to build “ranches.” There is a large amount of land lying idle around here. The field where we have our camp has not been farmed for two or three years. But there are some fine wheat fields here and the wheat is just heading out. We have a fine camp; all of the tents are raised now, and our brigade has shade trees set in rows throughout our camp. There being no trees, we went to the timber and cut down small bushy pine trees for the purpose, setting them in the ground. Our camp looked so fine that the staff artist of Harper’s Weekly took a picture of it for the paper.

Wednesday, April 22, 2015

22nd. Went to town in the morning to market. Will Hudson came out. We boys got together and had a jolly time. Floy and George came out. Good visit. Chester came home. Walked with Will to the river, too late for train. A lame stiff neck. Spent a part of evening at Minnie’s. Saw the Hudson family. F. Henderson and Will Keep. Hurrah!

Chattanooga, Saturday, April 22. The weather has taken an unaccountable cold turn, fire is comfortable all day. Drilled an hour on the gun this mornng. Lieutenant Jenawein appeared in camp this morning direct from the old 15th Army Corps. He left them at Goldsboro, N. C. He has been acting as ordnance officer for the artillery of the Corps. Looks well with his first lieutenant straps on. He is now our ranking lieutenant.

George Hill who left us three weeks ago, a mere skeleton, on sick furlough, has returned fat and plump. What a place Wisconsin must be. War news is very uncertain. Johnston’s army and Mobile are still in the ”bag,” but I guess they’ll soon come out of it.

Saturday, 22d April.

To see a whole city draped in mourning is certainly an imposing spectacle, and becomes almost grand when it is considered as an expression of universal affliction. So it is, in one sense. For the more violently “Secesh” the inmates, the more thankful they are for Lincoln’s death, the more profusely the houses are decked with the emblems of woe. They all look to me like “not sorry for him, but dreadfully grieved to be forced to this demonstration.” So all things have indeed assumed a funereal aspect. Men who have hated Lincoln with all their souls, under terror of confiscation and imprisonment which they understand is the alternative, tie black crape from every practicable knob and point to save their homes. Last evening the B——s were all in tears, preparing their mourning. What sensibility! What patriotism! a stranger would have exclaimed. But Bella’s first remark was: “Is it not horrible? This vile, vile old crape! Think of hanging it out when —” Tears of rage finished the sentence. One would have thought pity for the murdered man had very little to do with it.

Coming back in the cars, I had a rencontre that makes me gnash my teeth yet. It was after dark, and I was the only lady in a car crowded with gentlemen. I placed little Miriam on my lap to make room for some of them, when a great, dark man, all in black, entered, and took the seat and my left hand at the same instant, saying, “Good-evening, Miss Sarah.” Frightened beyond measure to recognize Captain Todd[1] of the Yankee army in my interlocutor, I, however, preserved a quiet exterior, and without the slightest demonstration answered, as though replying to an internal question. “Mr. Todd.” “It is a long while since we met,” he ventured. “Four years,” I returned mechanically. “You have been well?” “My health has been bad.” “I have been ill myself”; and determined to break the ice he diverged with “Baton Rouge has changed sadly.” “I hope I shall never see it again. We have suffered too much to recall home with any pleasure.” “I understand you have suffered severely,” he said, glancing at my black dress. “We have yet one left in the army, though,” I could not help saying. He, too, had a brother there, he said.

He pulled the check-string as we reached the house, adding, “This is it,” and absurdly correcting himself with “Where do you live?” — “211. I thank you. Good-evening”; the last with emphasis as he prepared to follow. He returned the salutation, and I hurriedly regained the house. Monsieur stood over the way. A look through the blinds showed him returning to his domicile, several doors below.

I returned to my own painful reflections. The Mr. Todd who was my “sweetheart” when I was twelve and he twenty-four, who was my brother’s friend, and daily at our home, was put away from among our acquaintance at the beginning of the war. This one, I should not know. Cords of candy and mountains of bouquets bestowed in childish days will not make my country’s enemy my friend now that I am a woman.

April 22d.—This yellow Confederate quire of paper, my journal, blotted by entries, has been buried three days with the silver sugar-dish, teapot, milk-jug, and a few spoons and forks that follow my fortunes as I wander. With these valuables was Hood’s silver cup, which was partly crushed when he was wounded at Chickamauga.

It has been a wild three days, with aides galloping around with messages, Yankees hanging over us like a sword of Damocles. We have been in queer straits. We sat up at Mrs. Bedon’s dressed, without once going to bed for forty-eight hours, and we were aweary.

Colonel Cadwallader Jones came with a despatch, a sealed secret despatch. It was for General Chesnut. I opened it. Lincoln, old Abe Lincoln, has been killed, murdered, and Seward wounded! Why? By whom? It is simply maddening, all this.

I sent off messenger after messenger for General Chesnut. I have not the faintest idea where he is, but I know this foul murder will bring upon us worse miseries. Mary Darby says, “But they murdered him themselves. No Confederates are in Washington.” “But if they see fit to accuse us of instigating it?” “Who murdered him? Who knows?” “See if they don’t take vengeance on us, now that we are ruined and can not repel them any longer.”

The death of Lincoln I call a warning to tyrants. He will not be the last President put to death in the capital, though he is the first.

Buck never submits to be bored. The bores came to tea at Mrs. Bedon’s, and then sat and talked, so prosy, so wearisome was the discourse, so endless it seemed, that we envied Buck, who was mooning on the piazza. She rarely speaks now.

Mrs. Lyon’s Diary.

April 22, 1865.—We started at five o’clock in the morning so as to get the cool of the day. Had a hard march. Got to Bull’s Gap in advance of the other troops.

April 26.—Now we have the news that J. Wilkes Booth, who shot the President and who has beenconcealing himself in Virginia, has been caught, and refusing to surrender was shot dead. It has taken just twelve days to bring him to retribution. I am glad that he is dead if he could not be taken alive, but it seems as though shooting was too good for him. However, we may as well take this as really God’s way, as the death of the President, for if he had been taken alive, the country would have been so furious to get at him and tear him to pieces the turmoil would have been great and desperate. It may be the best way to dispose of him. Of course, it is best, or it would not be so. Mr. Morse called this evening and he thinks Booth was shot by a lot of cowards. The flags have been flying all day, since the news came, but all, excepting Albert Granger, seem sorry that he was not disabled instead of being shot dead. Albert seems able to look into the “beyond ” and also to locate departed spirits. His “latest” is that he is so glad that Booth got to h—l before Abraham Lincoln got to Springfield.

Mr. Fred Thompson went down to New York last Saturday and while stopping a few minutes at St. Johnsville, he heard a man crowing over the death of the President. Mr. Thompson marched up to him, collared him and landed him nicely in the gutter. The bystanders were delighted and carried the champion to a platform and called for a speech, which was given. Quite a little episode. Every one who hears the story, says: “Three cheers for F. F. Thompson.”

The other afternoon at our society Kate Lapham wanted to divert our minds from gossip I think, and so started a discussion upon the respective characters of Washington and Napoleon. It was just after supper and Laura Chapin was about resuming her sewing and she exclaimed, “Speaking of Washington, makes me think that I ought to wash my hands,” so she left the room for that purpose.

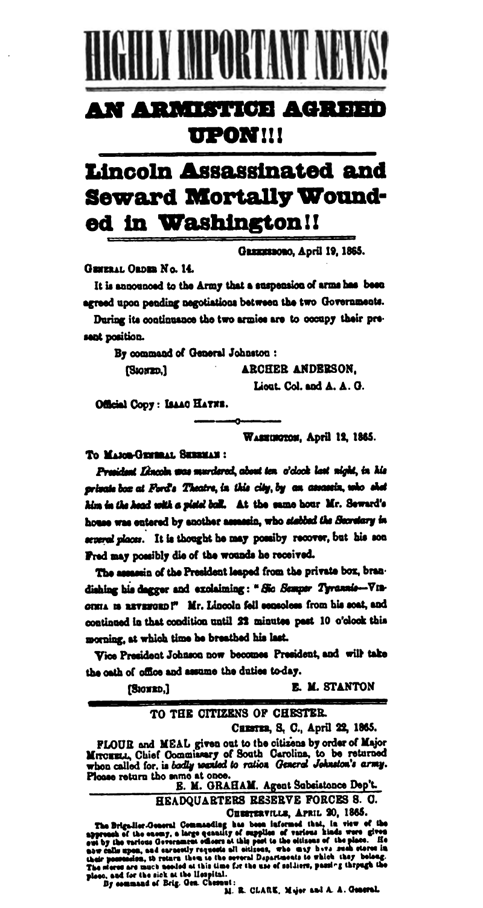

April 22.—There is much excitement in town. News has just come that there is an armistice, and that we had been recognized by France, England, Spain, and Austria; Lincoln has been assassinated, and Seward badly wounded. I was going down town when I heard great hurrahing: as we had heard that there was another raid coming, I was terribly alarmed, thinking it was the enemy coming in triumph, but was informed that it was a car filled with our men and Federals hurrying up to Atlanta, with a flag of truce, to let all know about the armistice. None of our people believe any of the rumors, thinking them as mythical as the surrender of General Lee’s army. They look upon it as a plot to deceive the people. Many think that Governor Brown has sold the state. There is evidently a crisis in our affairs.

April 22nd, 1865.—Aunt Margaret is going back to her home in Tennessee. She had letters today telling her General Fish had possession of her house as his headquarters. As soon as she can get the place she is going back. I will miss my jolly cousins dreadfully and Aunt Margaret too, but I know they will feel better to be at home once more. They have been refugees for four years and they must be tired of wandering.

Brother Junius looks more like himself. He has been to Neck-or-nothing Hall and found the plantation in good order and his servants were so glad to see him. His cook was loud in her denunciations of John, his man, who deserted to the enemy a year ago.

“Dat sure is a sorry nigger,” said she “ter up an’ leffen Marse Junius doubten nobody ter wait on him nur blacken his boots.”

His visit to his plantation did him good, we think. Father has conquered himself and you would never know how terribly he felt and must still feel, though, he is so cheerful and so helpful to others.