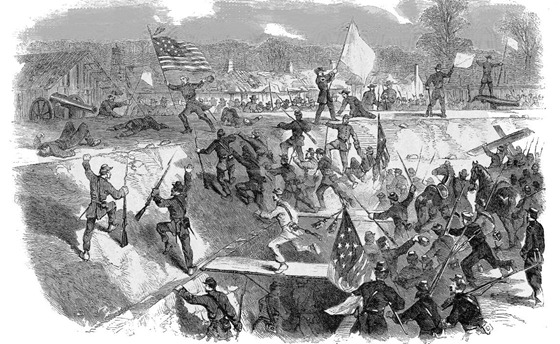

The Capture of Arkansas Post, Arkansas. – General S. G. Burbridge, Accompanied by his Staff, Planting the Stars and Stripes on the Rebel Fort Hindman, January 11. (Published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, February 14, 1863)

Army life in Virginia by George Grenville Benedict, 12th Regiment Vermont Volunteers.

The New Year And The Emancipation Proclamation.

Camp Near Fairfax C. H., Va., January 10, 1863.

Dear Free Press:

I must alter the 62 I have written by force of a twelve month’s habit, to 63—which reminds me that the old year has been made into the new since I wrote you last. The old year has taken with him three months of our term of service. We cannot hope that the coming months will deal with us as gently as have the past. Rough as portions of our army life have been, we have thus far seen but little of the roughest part of war. But it must come, though its approach is so gradual that we hardly perceive it. From the security of our camp of instruction on Capitol Hill we passed to the more arduous duties of work on intrenchments and picket service, at Camp Vermont. We exchanged that for our present more exposed position, where picket duty means watch for rebel cavalry, and where some of us have met and drawn trigger on the enemy. In time, no doubt, will come the still harder experience of protracted marches, of the shock of battle, of wounds and capture and death for some of us. More than this, the war as a whole is to be more desperate and deadly in future, because waged with a foe maddened by privations and loss of property, and especially by the President’s Proclamation of Freedom. We have already ceased to hear much talk about “playing at war.” It is owned to be work and pretty earnest work, now; and if it grows hotter as a whole, it will of course be the harder in its parts. But come what will, I for one—and I believe I am one of many thousand such—shall “endure hardness” more cheerfully, and fight, when called to, more heartily, because Freedom has been proclaimed throughout the land for whose unity and welfare we struggle, though its full accomplishment may cost years of trial and trouble.

Our present camp is on a pleasant slope, stretching out to the south-east to a broad campus on which take place the brigade drills to which General Stoughton treats the brigade almost daily. In the rear, the lines of tents extend into a fine grove of pines which kindly protect us from all winds but the east. A brook near by on our left, affords us water. A regimental order forbids the cutting of trees within 200 yards of the camp, and ensures to us the protection of our tall evergreens. The ground has been cleared and leveled, and the underbrush cut away from under the trees. On the whole, it is the pleasantest spot we have as yet occupied, and if we must spend the winter in this region, we shall be content to spend it here. The colonel and his staff have had their tents surrounded by sides of split logs with fire-places and chimneys of brick, and the men have raised their tents on stockades of logs, which detract somewhat from the appearance of the company streets, for it is impossible to give to a row of little log huts, plastered with mud, the neat appearance of a line of tents.

Our camp is graced by the presence of the accomplished wives of Colonel Blunt, Lieut. Colonel Farnham and Captain Ormsbee, who interest themselves in the hospitals and sick men, and give to us all, in a measure, the refining influence of woman’s presence, without which any collection of men becomes more or less of a bear garden.

The time of the regiment, at present, is mainly devoted to drill, with occasional episodes of picket duty; and we are on the whole making marked progress in discipline and drill. General Stoughton, in a general order issued a day or two since, declares that in these respects this brigade already compares well with the troops of other States, around us.

January 12.

My letter was interrupted by an order which sent the right wing of the Twelfth out on picket duty at Chantilly. The twenty-four hours did not pass without some incidents, which, if they were the first of their kind, might deserve mention; but having already given you some idea of picket duty here, I let them pass.

We are enjoying, this evening, a visit from our friend, and fellow-townsman to many of us, J. A. Shedd.

Yours, B.

Stuart’s Raid And Repulse From Fairfax Court House.

Camp Near Fairfax C. H., Va.,

December 29, 1862.

Dear Free Press:

We have been having rather stirring times during the past twenty-four hours. During the day on Sunday, rumors of a sharp engagement at Dumfries, twenty-five miles south of us, and the hurrying forward of troops to points threatened, reached us, and prepared us for a start. Just at night-fall came the command to fall in. Col. Blunt was absent at Alexandria, in attendance on a court martial, and Lieut. Col. Farnham was in command, by whom we were marched hastily to Fairfax Court House. The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Vermont regiments and the Second Connecticut battery, attached to our brigade, moved with us. We were hurried straight through the village, and it was not until we halted behind a long breastwork, commanding the sweep of plain to the east, that we had time to ask ourselves what it all meant. The word was soon passed about that a formidable rebel raid was in progress; that a large rebel cavalry force was approaching Burke’s Station, four or five miles below us; that an attack on Fairfax Court House was anticipated, and that Gen. Stoughton with the Vermont brigade must hold the position. Three regiments and three guns of the battery were to defend the village; the Fifteenth was at Centreville on picket, and the Sixteenth, with three guns, was sent to Fairfax Station.

The Twelfth manned the centre of the breastwork, extending across the Alexandria turnpike, along which the enemy was expected to advance. Two companies of the Thirteenth and a portion of the Fourteenth were placed on our right; the remainder of the Thirteenth on our left, and the balance of the Fourteenth a short distance in our rear. A brass howitzer and two rifled pieces were placed on the turnpike. Companies B and G of the Twelfth, under command of Captain Paul, were sent forward half a mile on the road, and a squad of the First Virginia (union) cavalry was placed still further out.

So arranged, we waited hour after hour of the bright moonlight night. Occasionally a mounted orderly dashed up to Gen. Stoughton with accounts of the rebel advance, but nothing specially exciting took place till about eleven, when suddenly the situation became interesting. First came a courier with a message for Gen. Stoughton, whose reply, distinctly audible to our portion of the line, was: ”Tell him my communication with Gen. Abercrombie is cut off; but I can hold my own here, and will do it.” Then came orders to load, and instructions for the front rank, —your humble servant was fortunate enough to be in that rank—to do the firing, if ordered to fire, and the rear rank to do the loading, passing the loaded pieces to their file leaders. Then came a dash of horsemen down the road, riding helter-skelter and “the devil take the hindmost.” We did not know then what it meant, but learned afterwards that it was the cavalry picket, driven in and frightened half to death by the rebels. The stir among our officers which followed told us, however, that it meant something. Col. Farnham rode along the line, giving the men their instructions. Major Kingsley added some words of caution and injunctions to fire low, and General Stoughton, riding up, said: “You are to hold this entrenchment, my men. Keep cool, never flinch, and behave worthy of the good name won for Vermont troops by the First brigade. File closers, do your duty, and if any man attempts to run, use your bayonets!” The captains, each in his own way, added their encouragements. The men on their part needed no incentive; and I have no doubt, had its possession been contested, that breastwork would have been held in a way which would have brought no disgrace on our Green Mountain State.

We had waited in silence a few minutes, when our ears caught a faint tramp of cavalry, half a mile away where our skirmishers were posted; then some scattered pistol shots; then shrill cheers as of a cavalry squadron on a charge; and then the flash and rattle of the first hostile volley fired by any portion of the Twelfth in this war. It was a splendid volley, too. Both companies fired at once, and their guns went off like one piece. The effects of the volley were not learned till daylight; but I may as well anticipate my story, and give them here. They were eight rebel troopers wounded and removed by their comrades—this our men learned from a man in front of whose house, a little ways on, the rebels rallied —three horses killed; three saddles, a rebel carbine, manufactured in Richmond, and a Colt’s revolver, picked up on the ground; and a horse, with U. S. on his flank, found riderless in the road and recaptured. The rebel troopers scattered in all directions but rallied further back. Our men expected a second charge, and were ready for it, but after a short halt the rebels turned and rapidly retreated.

At the breastwork we knew nothing of these details. We heard the firing, and taking it for the opening drops of the shower waited patiently for what should come next. Nothing came, however. All was still again. In half an hour camp fires began to show themselves about a mile in front, and our artillery was ordered to try its hand on them. Bang went the guns, under our noses, and whiz went the shells, but they drew no response. A reconnoissance was next ordered. Capt. Ormsbee of Co. G—one of our best captains—with 30 men of his own and Company B marched over to the fires. They were found to be fires of brush built to deceive us. A free negro, whose house was near by, informed Capt. O. that the rebels were under command of Generals Fitzhugh Lee and Stuart, both of whom had been in his house an hour before.

They had, he said, two brigades of cavalry and some artillery, and they had pushed on to the north. This news was taken to mean that they were making a circuit and would probably shortly attack from the north or west. We were accordingly double-quicked back to Fairfax Court House, and were posted (I speak now only of the Twelfth) on the brow of a hill, in good position to receive a charge of cavalry. Here we waited through the rest of the night. The moon set; the air grew cold; the ground froze under our feet; but we had nothing to do but to shiver and nod over our guns, till daylight. At sunrise we were glad to be marched back to camp, and to throw ourselves into our tents, where most of the men have slept through the day, taking rest while they can get it, for we are still ordered to be in readiness for instant marching. I doubt if we shall go out to-night, however. We hear to-day that the rebel cavalry, having made one of the most daring raids of the war, to within a dozen miles of Washington, have pushed on to Leesburg,[1] and will doubtless make a successful escape through the mountains.

I have given so much space to this little skirmish because it is the thing of greatest excitement with us at present, and not, of course, for its essential importance. But it has been an interesting bit of experience and not without value in its effect upon the discipline of the brigade. It has added to the confidence of the men in their officers, from Gen. Stoughton down, and I guess the men did not disappoint their commanders. To-day our colonel is again with us. He started with the adjutant to join the regiment last night by way of the turnpike, which was then held for two miles or more by the rebels, but was advised by Capt. Erhardt, in command of a squadron of the Vermont cavalry at Annandale, not to attempt to go through, and wisely took his advice. It would have been sorrow for us had he been taken by Stuart’s troopers.

December 30th.

We have spent an undisturbed night, and I have time this morning to add one or two more particulars of the affair of night before last. Our pickets have taken four or five prisoners of the rebel cavalry. One was a hard looking, butternut-clad trooper, apparently just recovering from a bad spree; he accounted for his used up appearance by averring that they had been six days in the saddle. The others were taken by the Vermont cavalry, and will go part way toward balancing the loss of Lieut. Cummings of Company D of the Vermont cavalry and three of his men, who were out on picket and were taken by Stuart’s men. It is ascertained that the forces of Stuart and Fitzhugh Lee made a circuit around us, passing between us and Washington and round to Chantilly on the west of us, where a body of 300 cavalry, including a portion of the Vermont cavalry, from Drainsville, came upon them; but finding themselves in the presence of a greatly superior force, retreated. It was reported in Washington, and fully believed by many, that our whole brigade had been captured.

Reinforcements have now been sent out to our support, and we anticipate no serious danger. Still affairs are in a rather feverish state, and we may be marched in any direction at any moment.

The weather is remarkable—days very mild, with magnificent sunshine; nights cooler, but still not much like Vermont.

Yours, B.

[1] This was erroneous. Stuart returned by way of Warrenton to Culpeper Court House.

Christmas In Camp.

Camp Near Fairfax C. H.,

December 26, 1862.

Dear Free Press:

We have had a very fair Christmas in camp. The day was as mild as May. By hard work the day before our mess had “stockaded” our tent and it is now a little log house with a canvas roof. We have in it a “California stove”—a sheet of iron over a square hole in the ground—and as we have been confined of late to rations of hard tack and salt pork, we decided to have a special Christmas dinner.

We got some excellent oysters of the sutler, also some potatoes. Two of the boys went off to a clean, free-negro family, about a mile off, and got two quarts of rich milk, some hickory nuts, and some dried peaches. I officiated as cook, and, as all agreed, got up a capital dinner. I made as good an oyster soup as one often gets, and fried some oysters with bread crumbs—for we are the fortunate owners of a frying-pan. The potatoes were boiled in a tin pan, and were as mealy as any I ever ate. We had, besides, good Vermont butter, boiled pork, good bread, and closed a luxurious meal with nuts, raisins and apples, and cocoa-nut cakes just sent from home. For supper we had rice and milk and stewed plums. Now that is not such bad living for poor soldiers, is it? But we do not have it every day; though we have had many luxuries since our Thanksgiving boxes came.

We have a pleasant camp ground just now, and if allowed to remain, shall make ourselves quite comfortable.

We had a visit from Dr. Thayer in our tent tonight. It was good for sore eyes to see the doctor and hear directly from home; and he will tell you when he gets back that he found here a right hearty looking set of fellows.

December 27th. We are in quite a stir to-night. Cannonading has been heard to the south all the afternoon[1] and we are under orders to be ready to march at a moment’s notice, with one day’s cooked rations. It is rumored that we are to be ordered forward in course of a week, anyhow.

Yours, B.

[1] This was the first engagement of Stuart’s raid, being his attack upon Dumfries, Va., and repulse by the garrison.

Picket Duty On Cub Run.

Picket Camp, Centreville, Va.,

December 19th, 1862.

Dear Free Press;

The main camp of our brigade is at Fairfax Court House, eight miles back of here. From thence a regiment is sent every four days to picket the lines in this vicinity. The turn of the Twelfth came day before yesterday. We started at 7.30 A. M., with two days’ rations in our haversacks, and were marched briskly hither over the Centreville turnpike, which has been so often filled with the columns of the army of the Potomac, in advance or in retreat. The skeletons of horses and mules, left to rot as they fell, were frequent ornaments of the highway, and the remains of knapsacks, bayonet sheaths, and here and there a broken musket, strewn along the road, told the story of strife and disaster in months and years gone by. Three hours brought us to the highlands of Centreville, covered with forts, eight of which are in sight from this camp, connected by miles of the rebel rifle-pits which kept McClellan so long at bay during the impatient months of last winter. One of the famous “quaker” guns lies near our camp.

The regiment halted here, and the right wing was at once despatched to the picket lines, Company C, under command of Lieutenant Wing, forming a portion of the detachment. Three miles of sharp marching across the fields, over a surface seamed with ditches and covered with a little low vine which tries its best to trip up the traveller, brought us, about noon, to the picket lines; and the men were at once distributed to the stations, to relieve the men of the Sixteenth regiment, who for four days had kept watch and ward on the line. The space allotted to Company C extended along the turbid stream of Cub Run, from a point near its junction with Bull Run, up to and beyond the ford and bridge where “Fighting Dick” Richardson opened the first battle of Bull Run, July 18th, 1861. Back from the stream a little are the camps of three Georgia and Kentucky regiments and a battery of rebel artillery, which wintered here last winter. The huts are of logs plastered with mud, with shed roofs of long split shingles or of poles covered with clay, each having a small aperture for a window, and capacious fire place and chimney of stone and mud masonry. They are a portion of the famous hut camps of Beauregard’s army, which cover the desirable camping spots for many a mile around, in which the rebel army spent a comfortable winter, while our army was shivering in tents. Our reserves are now posted in them—a picket reserve, as you know, is a body of 15 or 20 men, on which the pickets fall back for support if attacked, and from which men are sent at intervals to relieve the men on the lines—and we find them warm and comfortable shelter on these cold nights.

Let me describe to you a day and night of picket duty. We were stationed within hailing distance of each other, one man at a station for the most part, but sometimes two or three together at posts requiring especial vigilance, along the eastern bank of Cub Run, a small stream, a rod or two wide, which for the present is the boundary of Uncle Sam’s absolute control. Beyond it is debatable ground, a cavalry patrol of the First Virginia (loyal) cavalry, and occasional reconnoitering expeditions, alone disputing its possession with the enemy. A cavalry vidette is posted on the Gainesville road, and a patrol is sent out daily over the road for four or five miles.

We took our posts, in a flurry of snow, at noon. Each man’s thought was first of his fire and next of his dinner. The nearest fence or brush-heap furnishes the means of replenishing the one, the haversack supplies the other. From its depths the picket produces a tin plate, a piece of raw pork, a paper of ground coffee, and a supply of hard tack. If inclined for a warm meal, he cuts a slice or two of his pork and fries it on his plate, if less fastidious, he takes it raw with his hard bread. His cup is filled from his canteen and placed on the fire, and a cup of coffee is soon steaming under his nose. With such materials, and the appetite gained by a march of a dozen miles, a royal meal is soon made.

The afternoon passed with little incident. At my station I had a solitary visitor, a gaunt and yellow F. F. V., who came to say that he was anxious to save the rails he had left, around his cattle yard, and rather than have them burned he would draw some wood for the pickets—a suggestion which found favor with our boys, and the old fellow found occupation enough for himself, boy and yoke of oxen, for a good share of the day, hauling wood to the stations. He said he was a Virginian born, owned a farm of 150 acres, had no apples and no orchard to raise any with, no potatoes either, nothing that a soldier would eat except corn meal, and couldn’t sell any of that, as his supply was small and he could not cross the picket line to mill; had never taken the oath of allegiance nor been asked to take it; was a peaceable man himself, and meant to keep friends with the soldiers the best way he knew how; found some good men and some hard fellows among them on both sides; had lost a great deal by the war; but felt most the loss of his horses, which he said were taken from his stable while he was sick by some Union soldiers; had no slaves nor anybody to help him but his boy; had no gun of any description and never owned one; was glad to believe the war could not last forever, and only hoped it would be over in time to leave him some of his fences and timber.

At our reserve station, in the old rebel artillery camp, some stir was occasioned by a colored individual, one of a family of free negroes who own a fine farm of 400 acres just across the Run, who came in to say that a man believed to be a secesh soldier dressed in citizen’s clothes, had just been at his house and made inquiries as to the number and position of our pickets. Lieutenant Wing at once started out with two or three men, saw the fellow making tracks for the woods, and gave chase. He gained the timber, however, and made good his escape. As such a search for information might be preliminary to a rebel dash on our picket line, the affair had a tendency to put our men on the alert. Further down the line the men of another company, while scouting round a farmhouse, discovered in the barn a suspicious looking box, which, when opened, disclosed within a metallic burial case, containing a corpse, which the family there averred to be the body of a Southern officer, which was left there on the retreat of the rebel army last March, with directions to keep it until it should be sent for. But it had not been sent for and perhaps never will be.

The night settled down clear and very cold. — With the darkness came orders to put out the picket fires or keep them smouldering without flame. Your humble servant was stationed on the bank of Cub Run, opposite a rude foot bridge thrown across the stream. My turns of duty were from 4 to 8 and 10 to 12 P. M., and from 2 to 4 and 6 to 8 A. M. The stars shone bright; but there was little else to see. The stream rippled away with constant murmur and the wind sighed and rustled through the trees; but there was little else to hear, till about midnight, when the reports of fire arms came from the direction of the cavalry vidette, further out on the battlefield, two or three miles away, and shortly after a sound of the clatter of hoofs on the frozen ground. The sound died away and the night was still as before. When I was relieved and returned to the reserve, the fires were burning brightly in the wide fire places, and seated around we told stories and cracked jokes, and discussed the campaign, and wondered where Banks had gone. Suddenly a hasty step is heard without, and one of the pickets puts in his head at the door to announce that men are moving on the opposite bank of the stream. While he is talking, bang goes a musket from our line to the left, and then another. Something is going on, or else somebody is unnecessarily excited. We seize our pieces, and hurry down to the ford, close by, where if anywhere a rebel party would probably attempt a crossing, and are not quieted by hearing in a whisper from the three trusty men stationed there, that a small party of men had just come stealthily along the opposite bank, stopped at the ford, discussed in a low tone the expediency of crossing, and then, disturbed by the firing and stir down our line to the left, had hastily retired.

Our boys kept quiet, for the comers were invisible in the shadow of the opposite bank; had they stepped into the water they would have been fired on. Of course they might return and more with them, and dropping low, so as to get a sight against the star-lit horizon, we awaited developments. A hostile body attempting the crossing about there would have met the contents of fifteen rifled muskets, tolerably well aimed. But no more sound was heard, and the reserve returned to their post. A sergeant and two men, sent down the line, had in the meantime discovered that the shots heard were fired by two of our sentinels, who hearing a movement in the bushes across the run, had fired at random. I returned to my sentry post, but there was no more alarm. I saw the big dipper in the North tip up so that its contents, be they of water, or milk from the milky way, must have run out over the handle. I saw the triple-studded belt of Orion pass across the sky. I saw two meteors shoot along the horizon, and that was all the shooting. I saw the old moon, wasted to a slender crescent, come up in the east. I saw the sun rise very red in the face at the thought that he had overslept himself till half past seven, on such a glorious morning. I heard a song bird or two piping sweetly from the woods; but I neither saw nor heard any rebels. With daylight, however, a Union cavalry man, on foot, bareheaded, with scratched face and eyes still wild with fright, came to our line and told a story which explained the alarm of the midnight. The cavalry vidette, sixteen in number, of which he was one, posted out some three or four miles, while sleeping around their fires had been charged into by a party of White’s rebel cavalry, who captured all their horses and seven or eight of their number; the rest scattered into the bush in all directions, and it was doubtless some of them trying to make their way into Centreville, who created the alarm along our line, and came so near being fired on by our men at the ford.

December 20.

I hear this morning that the infantry pickets are to be withdrawn from the line along Cub Run, letting cavalry take their places, and that we shall go into the redoubt close by, to-day, to be relieved, I suppose, to-morrow, by another regiment of the brigade. A grand review of the other four regiments by General Stoughton took place yesterday at Fairfax Court House.

Yours, B.

The Brigade Moves To Fairfax Court House.

Camp Near Fairfax Court House, Va.,

December 15th, 1862.

Dear Free Press:

More moves on the big chess board of which States and counties are the squares and divisions and brigades the pieces. And as the older troops push to the front, the reserves, of which the Second Vermont brigade is a portion, move up and occupy the more advanced positions of the lines of defense around Washington, vacated by our predecessors.

General Sigel’s division marched to the support of Burnside last week, and our brigade has stepped into their deserted places. Our five regiments are now in camp round Fairfax Court House and along the line to Centreville, doing picket duty on the lines near the latter place.

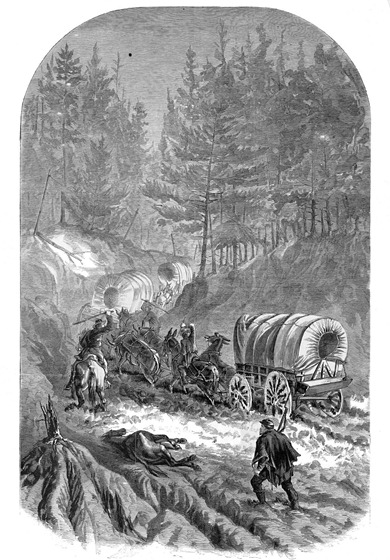

The orders for us to march came on Thursday evening last, while the Twelfth was out on picket. The boys were ordered in and reached camp about 10 o’clock. They came in singing “John Brown” and camp was soon humming with the bustle and stir of breaking camp. Big fires made of the no longer needed packing boxes which came from Vermont, were soon blazing in the company streets, and the work of packing knapsacks began. With most of the boys the first thought was for the creature comforts still remaining from the Thanksgiving supply, and each man proceeded to make sure of some of them, by putting himself outside of such a portion as his capacity would admit of, be the same more or less. It was midnight before the camp was still. After two hours or so of slumber we were aroused; reveille was sounded at 3; the tents were struck at 4; the line of march was formed at 5; and by 6 the brigade was on its way. The morning was a magnificent one, clear, rosy and frosty, and the step of the men was light and springy as they filed away. I was on special duty and did not accompany the column. At 4 o’clock P. M. the Twelfth halted at their present camping ground about a mile west of Fairfax Court House, having with the brigade accomplished a march of twenty miles. Though the pace was moderate and the stops frequent, it was altogether the severest march as yet made by our regiment. It is to be remembered that in such a march the weight of the packed knapsack about doubles the amount of exertion. Most soldiers would prefer a march of twice the distance in light marching order. Our boys marched well, however. But twelve of the Twelfth fell to the rear—a proportion of stragglers less, as I am told, than that of any of the other regiments. Of Company C, one man, just convalescent from a three weeks’ run of fever, who should not have attempted to march at all, was taken up by one of the ambulances. Another man who had been off duty from ill health came in with the stragglers; the rest, to a man, marched into our present camp with the colors.

I returned to Camp Vermont the day after. The Third brigade of Casey’s division was already installed in the winter quarters built with so much labor by the Vermont regiments. The Fourth Delaware was in the camp of the Twelfth, and a new order of things was in force. The quiet and discipline of the Vermont camps had disappeared. Muskets were popping promiscuously all around the camps; much petty thieving appeared to be on foot; and Mr. Mason, the gray headed “neutral” who owns the manor, was praying for the return of the Vermont brigade. His fences were lowering with remarkable rapidity; the roofs of some of his out-houses had quite disappeared, and Colonel Grimshaw, commanding the brigade, had his headquarters in the front parlor of his mansion. I could not give him a great deal of sympathy, for I believe him to be a rebel; but I was glad the spoliation was not the work of our Vermont boys.

I followed the regiment on Sunday, taking the military railroad train to Fairfax Station. Here, and all along the road to the dirty little village of Fairfax Court House, four miles to the north, I struck the column of an army corps pushing on to the front. Here a drove of beef cattle; next a battery of Parrot guns; there a travel worn regiment, marching with tired lag and frequent hunching up of their heavy knapsacks; then one resting by the wayside; then a battery of brass twenty-pounders; then another regiment and another; and long white lines of army wagons filling every vacant rod of road for miles and miles as far as the eye could reach. It was the rear of the Twelfth Army Corps, from Harper’s Ferry and Frederick, en route for Dumfries to be in supporting distance of Burnside; and for over twenty hours the stream of men and material of war had flowed over the road in the same way. It is only after seeing such a movement that one begins to realize something of the size of the business which is now the occupation of the nation.

I turned from the road across the fields to a pine grove in which lay the camp of the Twelfth. The regiment was drawn up in square at the edge of the timber. As I drew near, the strains of “Shining Shore” broke the stillness, and as I joined the body, the men were standing with bared heads, as the chaplain invoked the blessing of God on our cause, on our fellow soldiers now perhaps in deadly fight,[1] on our own humble efforts, and on the homes we left to come to the war. It was a transition, in a step, from the strong rush of the tide of war to a quiet eddy of Christian worship, and the contrast was a striking one.

We are at present under shelter tents, pitched promiscuously among the pine trees. The weather is mild and fine, and the ground as dry as May. We can hardly realize that it is the middle of December. How long we shall remain here, of course we do not know.

A new brigade band of seventeen pieces has been organized under the leadership of Mr. Clark of St. Johnsbury, whose concerts in Burlington you doubtless remember. The music for dress parade to-night was furnished by the band and was a decidedly attractive feature.

Our new Brigadier General, Stoughton, came and took command a week ago yesterday, and Colonel Blunt has returned to the command of the Twelfth. During his absence Lieut. Colonel Farnham has shown every quality of an efficient and courteous regimental commander.

We are waiting with intense interest for news of the results of the movements on Richmond. Providence seems to be smiling on us, in this fine weather, and we cannot doubt the triumph of our arms. If between Burnside and Banks the rebel capital cannot be taken, who shall next attempt the job?

P. S. The rain has come before our tents have, and a juicy time is in progress.

Yours, B

[1] Gen. Burnside was now in command of the Army of the Potomac, and having fought the disastrous battle of Fredericksburg, Dec. 13, was now about to recross the Rappahannock.

Thanksgiving Day In Camp.

Camp Vermont,

Fairfax Co., Va., Dec. 6, 1862.

Dear Free Press:

One or two noticeable events have broken the monotony of our camp life since I wrote you last. The first was the departure of three regiments of the brigade, which took place ten days ago. The order came at 8 o’clock in the evening, and the “bully Thirteenth,” as its boys delight to call themselves, was on the march through our camp at nine, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth following with little delay. The Twelfth had orders to pack knapsacks and be in readiness to move at a moment’s notice, and our own camp was all astir with the bustle of preparation. The night was dark and rainy, and as the other regiments passed on the double quick through our camp, their dark columns visible only by the light of the camp fires, our boys cheering them and they cheering lustily in response, the scene was not devoid of excitement. Every man in the ranks believed that such a sudden night march to the front meant immediate action, and the haste and hearty shouting showed that the prospect was a welcome one. The Twelfth would have gone with equal cheerfulness; but the expected order for us to fall in did not come. We have remained, doing picket duty with the Sixteenth. The service takes about all the effective men of each regiment, each going on for 48 hours. The marching to and from consumes the best part of another day, making in effect three days’ hard duty out of every four. As the weather has been cold, and most of the boys get little sleep at night while out, they have found the duty pretty severe; but they take it for the most part without murmuring. The return of the other regiments, all three of which have come back to us, will, however, greatly lighten the service hereafter.

Thanksgiving was the second “big thing” of the past fortnight. It was not quite what it would have been had the six or seven tons of good things sent to different companies from Vermont arrived in season; but it was emphatically a gay and festive time. The day was clear, air cool and bracing, sunshine bright and invigorating. The boys of our company made some fun over their Thanksgiving breakfast of hard tack and cold beans, but possessed their souls in patience in view of the forthcoming feast of fat things, for we had heard that our boxes from home were at Alexandria, and the wagons had gone for them. At 10 o’clock the regiment assembled for service. Gov. Holbrook’s proclamation was read by Chaplain Brastow, and was followed by an excellent Thanksgiving discourse. At its close, Col. Blunt addressed the regiment, expressing his thankfulness that he could see around him so many of his men in health; urging an orderly observance of the day; and inviting the men to meet the officers after dinner on the parade ground for an hour or two of social sport and enjoyment. An hour later the teams arrived with but four of the forty big boxes expected, and the unwelcome news that the rest would not reach Alexandria till the next day. Most of the companies were in the same predicament. Company I had a big box, and made a big dinner, setting the tables in the open air, to which they invited the field and staff officers. Two or three men of Company C received boxes, with as many roast turkeys, which they shared liberally with their comrades, so that a number of us had Thanksgiving fare, and feasted with good cheer and a thousand kind thoughts of the homes and friends we left behind us. We knew that they were thinking of us at the same time. If each thought of affection and good will had had visible wings, what a cloud of messengers would have darkened the air between Vermont and Virginia that day!

At 2 o’clock, the regiment turned out on the parade ground. The colonel had procured a foot ball. Sides were arranged by the lieutenant colonel, and two or three royal games of foot ball —most manly of sports, and closest in its mimicry of actual warfare—were played. The lieutenant colonel, chaplain and other officers, mingled in the crowd; captains took rough-and-tumble overthrows from privates; shins were barked and ankles sprained; but all was given and taken in good part. Many joined in games of base ball; others formed rings and watched the friendly contests of the champion wrestlers of the different companies; others laughed at the meanderings of some of their comrades, blindfolded by the colonel and set to walk at a mark. It was a ”tall time” all round. Nor did it end with daylight. In the evening a floor of boards, laid upon the ground, furnished a ball room, of which the blue arch above was the canopy and the bright moon the chandelier. Company C turned out a violin, guitar and two flutes for an orchestra; some other company furnished another violin, and a grand Thanksgiving ball came off in style. I did not notice any satin slippers. The ”light fantastic toe” was for the most part clad in ‘‘gunboats,” as the men call the army shoes, and the nearest approach to crinoline was a light blue overcoat; but the list was danced through, from country dances to the lancers, and the gay assembly did not break up until half-past nine.

So ended Thanksgiving day proper; but the enjoyment of the bigger portion of the creature comforts sent our company from Vermont is yet to come. Our Thanksgiving boxes came yesterday after the regiment had gone out on picket; and the few men left behind in camp have been sampling some of the more perishable articles, though booths of brush and picket fires almost extinguished by the snow, are hardly what one would choose as surroundings.

The Thanksgiving dinner of the officers’ mess of Company C came off to-day, and was a highly select and recherche affair. The board was spread in the capacious log shanty of Maj. Kingsley and was graced by the presence of the amiable wife of Col. Blunt, who has been domiciled in camp for a week or two, and of the field and staff officers of the Twelfth and the chaplain and surgeon of the Fifteenth. I enclose a copy of the bill of fare, in the composition of which I suspect my editorial brother, of the quartermaster’s department, had a hand. It was engrossed on brown wrapping paper, like the Southern newspapers, and every thing on the bill was on the board, sumptuous as it may seem. The good things said I do not feel at liberty to report.

The Thanksgiving dinner of the officers’ mess of Company C came off to-day, and was a highly select and recherche affair. The board was spread in the capacious log shanty of Maj. Kingsley and was graced by the presence of the amiable wife of Col. Blunt, who has been domiciled in camp for a week or two, and of the field and staff officers of the Twelfth and the chaplain and surgeon of the Fifteenth. I enclose a copy of the bill of fare, in the composition of which I suspect my editorial brother, of the quartermaster’s department, had a hand. It was engrossed on brown wrapping paper, like the Southern newspapers, and every thing on the bill was on the board, sumptuous as it may seem. The good things said I do not feel at liberty to report.

We have had our second snow storm. It began yesterday, and continued through a bitter night. Toward night the Thirteenth and Fourteenth regiments came in from Union Mills—the Fifteenth came in the night before—and marched into their deserted camps, close by us. They brought only shelter tents, and the prospect of camping down in the snow, with little food, no fuel, and scanty shelter, was a pretty black one for them, till our officers went over and offered the hospitalities of the Twelfth, which were gratefully accepted. The absence of most of our men on picket, left a good deal of vacant room in our tents, which were soon filled with wet and tired men of the other regiments. They went away this morning warmed, rested and fed.

The weather to-day is very cold and I fear that our boys on picket will suffer to-night, though they will have frozen ground to lie on instead of muddy slush, which will be so far an improvement.

The health of the regiment continues much better than the average of the brigade.

Sunday Morning, December 9.

We hear that General Stoughton will assume command to-day. The brigade would, however, I think, be satisfied to remain under command of Colonel Blunt. Thermometer only 15° above zero to-day.

Yours, B.

Losses By Death—An Abortive Review.

Camp Vermont,

Fairfax Co., Va., Nov. 24, 1862.

Dear Free Press:

Death has again invaded the circle of our company and has taken one of our best. We miss William Spaulding much. We did not expect to bring back all we took away from Burlington, but if asked which would probably be of the first to yield to the exposures of army life, who would have pointed out that fine handsome boy? It seems hard that such should be sacrificed to the demon of rebellion. He had in him the making of a first rate soldier and a useful man. The regularity with which he performed all his military duties, from the day of his enlistment till disabled by sickness, was matter of remark; and his tall figure and pleasant face, in the first file of the company, was always a pleasant sight. He began to lose flesh and strength without any apparently sufficient reasons, and finally went into the regimental hospital; grew better, was placed on guard at a private house near here, where he had the shelter of a roof, caught cold, and died from congestion of the lungs. Captain Page, Lieutenant Wing, the chaplain and surgeon, did all they could for him. He received calmly the intelligence that he must die, said he was ready, sent words of parting remembrance and admonition to his friends, and passed away quietly. His death has cast a shadow over the company, and we ask ourselves, “who will be the next?”

One of the line officers of the regiment, Lieutenant Howard of the Northfield company, died in the hospital on Friday, from inflammation of the brain. The two deaths were made the occasion of some impressive remarks by Chaplain Brastow, at divine service yesterday.

Many as are the contrasts between our life in the army and that we lead at home, there is none greater than that between our Sabbaths there and here. As we stood at regimental service yesterday, our chapel a vacant spot before the colonel’s tent, our heads canopied only by the grey clouds drifting swiftly to the southwest, and the chill November wind blowing through our ranks, I could not but cast back a thought to the quiet and comfortable New England sanctuaries many of us have been wont to worship in. But we were better off than most of the regiments in the army, for but few of them, probably, had any Sabbath service at all.

We have had four days of rain and I have the facts for an essay on Virginia mud, whenever I get time to write it, and I assure you it is a deep subject.

Orders were out on Thursday for a grand review at Fort Albany, six miles from here, of all the forces on this side of the river. It was the third and hardest day of the storm. A countermand was expected; but none came, and the Twelfth, with three other regiments, took up its line of march. The mud varied from a thin porridge of one part red clay to three parts water, to a thick adhesive salve of three parts clay to one of water—there or thereabouts—I may not give the proportions exactly. It was a hard march. The foot planted in the red salve alluded to, is lifted with some difficulty, and comes up a number of sizes larger, and three or four pounds heavier. A mile or two of such marching tries the sturdiest muscles. The march of our boys was that of a host of conquering heroes. They took the whole country—along with them, on their soles. In the lack of any affection on the part of the inhabitants, it was delightful to find such a strong attachment on the part of the “sacred soil.” These were the only compensations. We couldn’t see, somehow, the connection between this tramp through the mud, and the business of crushing out the rebellion; and when, a mile beyond Alexandria, a courier met the column with orders to return to camp, the suspicion that all might just as well have staid in camp, became general. The substance of the proceeding was that four thousand men had a march of eight miles in a storm which made the bare idea of a review an absurdity—that was all. Perhaps “somebody blundered.”

The winter quarters of this regiment are to be long huts, one for a company, made of logs set endwise in the ground, on which a roof of boards will be placed. They make slow progress. The truth is this brigade has a good deal to do. Our regiments have a picket line of six miles to guard, the nearest point of which is five or six miles from camp. They furnish a thousand men daily, in good weather, to dig in the trenches of Fort Lyon. They have to cut the timber for their winter quarters and construct the same, and they have to fill up the interstices of time with drill. If Uncle Sam’s $20 a month is not pretty generally earned, so far, in this brigade, some of us are much mistaken.

The picket service is becoming arduous. The pickets are out 48 hours. At many of the stations no fire is allowed, and especial vigilance is enjoined, so that little sleep can be obtained; and with all precautions there is a chance of meeting a shot from some of the rebel spies and straggling guerrillas who hover around the outer circle of our lines. Saturday night a couple of the boys in our company were thus fired on. Add to these inconveniences the special discomforts of rain and deep mud, and picket service becomes anything but romantic.

A sad event occurred on Wednesday on the picket line. A corporal of the Fourteenth regiment while instructing a soldier how to halt and cover with his piece any suspected enemy approaching the station, fired off his gun, shooting the man through the breast. The wound was a terrible one, and I am told the man must die.

I noticed in a letter from the Thirteenth regiment, printed in the daily Times a week or more ago, a statement that but few of the articles sent from home for the comfort of sick soldiers ever reach them, owing to the fact that the officers appropriate them to their own use. There may be individual cases of that sort, take the army through; but that such theft from sick men, of the things they prize most, is customary down here, I do not believe. I know that in the hospital of the Twelfth the things sent in for the soldiers are put to their proper use. I am a frequent visitor at the hospital and have been glad to note the improvements added daily. Its area has been enlarged, while the number of patients has decreased. It is floored and boarded up on the sides. Neat iron bedsteads have been supplied, and the sick men sleep between sheets furnished by the Ladies’ Relief Association of Washington. It is to the credit of Surgeon Ketchum that his hospital is comfortable far beyond the average. Mr. S. Prentice, of the Committee of the Vermonters’ Relief Association, Washington, is a frequent visitor, and brings supplies of needed articles.

The visit of the Committee of the Ladies of Burlington, Mrs. Dr. Thayer and Mrs. Platt, to our camp yesterday, accompanied by Mrs. Chittenden and Dr. Hatch, was a most agreeable surprise. It was a double pleasure to see faces from home, and ladies’ faces, which are novelties in camp.

The weather has come off fine, clear and frosty after the storm.

Yours, B.

An Ordinary Day In Camp.

Camp Vermont,

Fairfax Co., Va., Nov. 14, 1862.

Dear Free Press:

You have discovered that I make little or no mention of army movements; nor do I indulge in criticism or speculation in regard to the course of the war in any of its parts. Such matters I leave to the correspondents from headquarters. My object is to give your readers, so many of whom have friends in our ranks, some idea of our life and business, as seen, not from the officer’s marquee or the reporter’s saddle, but from the tent of the private. I have nothing to write, consequently, about the recent change in the chief command of the Army of the Potomac, or its probable results. I may say, however, that there has been no mutiny in the Second Vermont brigade in consequence of General McClellan’s removal, and that any change that promises more active and efficient service for the army, will have our hearty approval, as a portion of the same.

In the absence of any thing especially exciting, let me try and describe, briefly, an ordinary day in camp. You are perhaps, familiar enough with the regular arrangement of tents in a regimental camp. The tents of the colonel and his staff are commonly disposed in a line at the rear of the camp. In a parallel line with them are the tents of the line officers, each captain’s tent fronting the street of his company. The company streets run at right angles to the line of the officers’ tents, and are of variable widths, in different camps, according to the extent of the ground. In our present camp they are about twenty-five feet wide. On each side are the company tents, nine on a side, facing the street on either side. At the inner end of the street, on one side, is the cook tent, occupied by the company cooks and stores, and in front of it is the “kitchen range.” Whose patent this is, I cannot say. It is composed of a trench, four feet long and two deep, dug in the ground. In the bottom of this the fire is kindled. Forked sticks at the corners, support a couple of stout poles, parallel with the sides, across which are laid shorter sticks on which hang the kettles. With this apparatus, and an oblong frying pan of formidable dimensions, say three feet long by two wide, is done all the cooking of the company.

The first signs of life, inside of the lines of the main camp guard, are to be seen at these points. The cooks must be up an hour or two before light, to get their fires started and breakfast cooking. The fires on the cold mornings, and most of the mornings are cold, are objects of attraction to those of the soldiers who for any reason have lain too cold to sleep. These come shivering to the fires, and watch the cooks and warm their shins, till reveille. There are stoves now, however, of some sort, in most of the tents, and almost all can be as warm as they wish at any time.

At daybreak the drum major marshals his drum and fife corps at the centre of the line, and the reveille, with scream of fife and roll of drum, arouses the sleeping hundreds, lying wrapped in their blankets under the canvas roofs. The reveille is a succession of five tunes, of varying time, common and quick, closing with three rolls, by the end of which each company is expected to be in line in the company street. The men tumble out for the most part just as they have slept, some with blankets wrapped about them, some in slippers and smoking caps, some in overcoats. They fall into line and the orderly sergeant calls the roll and reads the list of details for guard, police, fatigue duty, etc. After roll call, many dive back into their tents and take a morning nap before breakfast; others start in squads for the brook which runs close by the camp, to wash. The fortunate owners of wash basins—there are two in our company—bring them out, use them, and pass them over to the numerous borrowers; others wash in water from their canteens, one pouring on the hands of another. ”Police duty” comes at 6.15, and is performed by a squad under direction of a corporal. This varies slightly from the popular notion of such duty, which is commonly supposed to consist in wearing a star and standing round on city street corners, with the occasional diversion of clubbing some non-resistant citizen. In camp “police duty” corresponds to what, when I was a boy, was called clearing up the door yard. The sweeping of the company streets, removal of unsightly objects, grading of the grounds, and work of similar character, comes under this head. At half past six comes the “surgeon’s call.” This is not a call made by the surgeon, who is not expected to appear in company quarters unless for some special emergency; but of the orderly sergeant, who calls for any who have been taken sick in the night, and feel bad enough to own it and be marched off to the surgeon’s tent, where, after examination, they are ordered into hospital or on duty, as the case may require.

Breakfast takes place at 7, by which time, in well ordered tents, the blankets have been shaken, folded, and laid away with the knapsacks in a neat row at the back of the tent, and the soldiers start out, cup in hand, for the cook tent, where each takes his plate with his allowance of bread and beef or pork, and fills his cup with coffee. Some sit and eat their breakfast on the wood pile near the fire; but most take their meals to their tents. The straw covered floor is the table, a rubber blanket the table cloth, and sitting round on the ground like so many tailors, we eat with an appetite which gives to the meal a zest almost unknown before we came “a sogering.” Our meals do not differ greatly, the principal difference being that for dinner we have cold water instead of tea or coffee. The rations are beef, salt and fresh, three-fifths of the former to two of the latter, both of fair quality; salt pork, which has uniformly been excellent; bread, soft and hard, the former equal to first rate home-made bread, the latter in size, taste and quality resembling basswood chips—very wholesome, however, and not unpalatable; rice, beans, both good, and potatoes occasionally; coffee fair, and tea rather poor. Butter, which when good is one of the greatest luxuries in camp, cheese, apples, which with most Vermonters are almost an essential, and other knickknacks, are not furnished by government, but may be bought of the sutlers at high prices. Our men are great hands for toast; and at every meal the cook-fires are surrounded with a circle of the boys holding their bread to the fire on forked sticks or wire toast racks of their own manufacture, and of wonderful size and description. So we live, and it shows to what the human frame may be inured by practice and hardship, that we can eat a meal of good baked or boiled pork and beans, potatoes, boiled rice and sugar, coffee and toast, and take it not merely to sustain life, but actually with a relish—curious, isn’t it?

Dinner is at 12, dress parade at 4:30, and supper at 5:30. The heavy work of the men fills the intervals. This varies. At Capitol Hill it was company and battalion drills. Here it is digging in the trenches of Fort Lyon, and cutting lumber in the woods near by, for our winter quarters. Evenings are spent very much as they would be by most young men at home, in visiting their comrades, playing cards and checkers, writing letters, and reading. A common occupation of a leisure hour, with the smokers, is the carving of pipes from the roots of the laurel, found in profusion in the woods here. It is a slow business, in most cases beginning with a chunk about half as large as one’s head, which is reduced by slow degrees and patient whittling to the small size of a pipe bowl. Another common, but not so delightful pastime, is the washing of one’s dirty clothes. Many of our men have learned to be expert washers, and that without wash-board or pounding-barrel. Those who have pocket money, however, can have their washing done by the “contraband” washerwomen, who have been on hand at every camp we have occupied.

At half-past eight P.M. the tattoo is sounded by the drum and fife corps, playing several tunes as at reveille, when each company is again drawn up in its street and the roll called. At nine comes “taps,” when every light must be out in the tents, and the men turn in for their night’s rest. The ground within the tents is covered with straw or cedar branches, on which are spread the rubber blankets; this is the bed, the knapsack is the pillow. There is no trouble about undressing; our blouses, or flannel fatigue coats, pantaloons and stockings, sometimes with overcoat added, are the apparel of the night, as of the day. We slip off our boots, drop in our places side by side, draw over us our blankets; and sleep, sound and sweet, soon comes to every eyelid. The man who can sleep at all, in camp, commonly sleeps soundly and well.

I spoke in the beginning of this letter of the absence of anything exciting in camp. We have since had something particularly exciting for Company C—the arrival of some boxes of good things sent by our kind friends in Burlington. We had had warning of their coming and were anxiously awaiting them. They reached camp after dark last evening; but the noise of unloading before the captain’s tent told everyone that they had come, and an eager crowd hurried to the spot. A couple of pickaxes were quickly put in use. The covers flew off as if blown upwards by the explosive force of the good will and kind feeling imprisoned within, and the parcels were quickly handed out to the favored ones, who thereupon disappeared within the tents, from which shouts of joy and laughter would come pealing as the things within were unpacked. What unrolling of papers and uncovering of boxes there has been, and uncorking of jars and bottles and munching of good things in every tent! A bevy of children, in holiday time, were never more pleased with their presents than we with our home luxuries, made doubly delicious by our confinement to army fare, and trebly valuable because they were from the friends at home. The whole thing was pronounced emphatically “bully.” I beg you will divest this word of anything of coarseness or slang it may heretofore have had. It is the adjective which in the army expresses the highest form of admiration and is in constant use from the colonel and chaplain to the lowest private. When the soldier has pronounced a thing “bully,” he can say no more. I wish you could have heard—and if you had listened sharply I think you might—the cheers and tiger which after roll call at tattoo last night, were given by Company C “for our friends in Burlington.”

The health of the regiment is improving. We have but thirteen men on the sick list, and none dangerously ill.

The picket line our brigade is guarding has been moved out several miles, and now runs about two miles this side of Mt. Vernon. The weather is fine and the spirits of the men good. But they do not take kindly to “fatigue duty” on the trenches. They think they had rather be engaged in chasing or fighting rebels than in “strategy,” however important the latter may be in all wars. Yours, B.