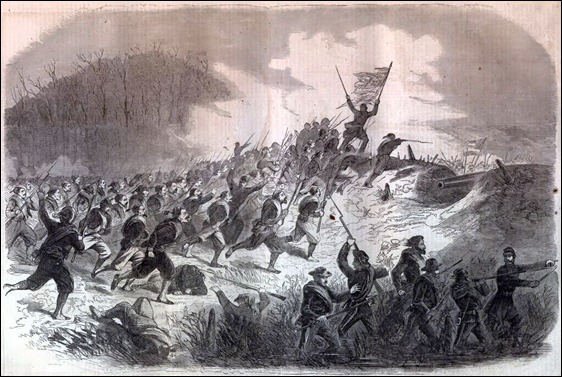

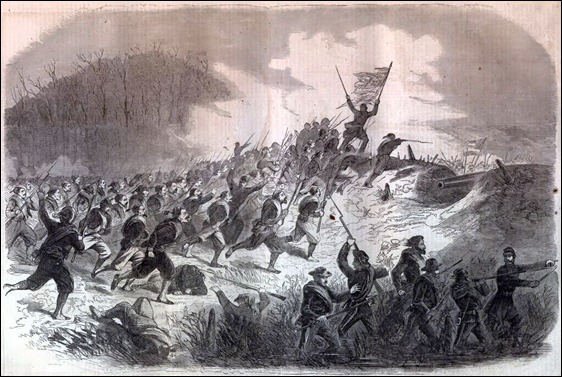

Gallant Charge of Hawkin’s Zouaves upon the Rebel Batteries on Roanoke Island.

March 1, 1862 issue of Harper’s Weekly, page 135:

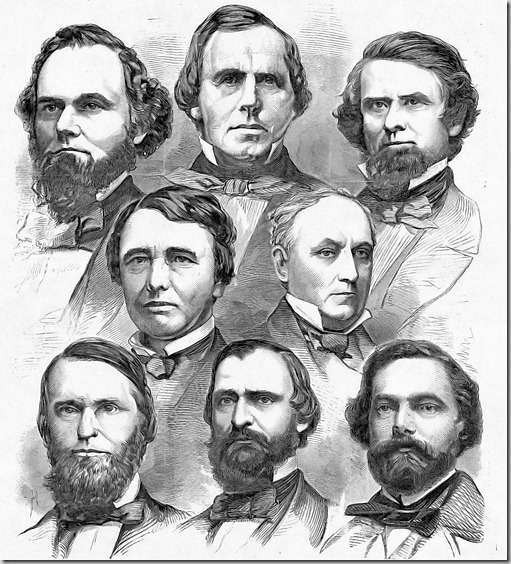

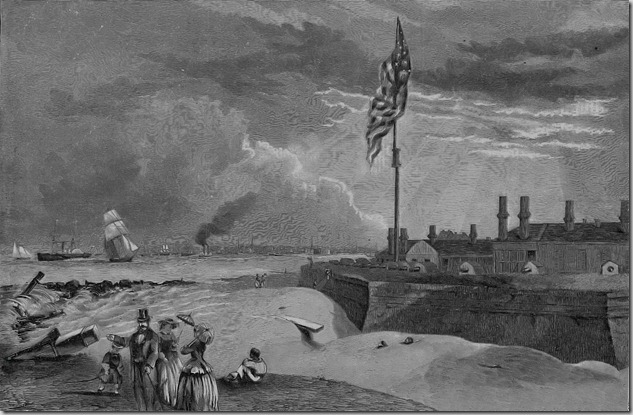

We devote a large portion of our space this week to illustrations of the Burnside Expedition. On page 136 we give portraits of the commanders GENERAL BURNSIDE and FLAG-OFFICER GOLDSBOROUGH; on the same page a picture of the DESTRUCTION OF THE REBEL NAVY UNDER COMMODORE LYNCH; on page 137 an illustration of the CHARGE OF HAWKINS’S ZOUAVES upon the rebel batteries; on page 140 a portrait of GENERAL FOSTER, who received the surrender of the rebel troops; on page 134 A CHART OF ALBEMARLE SOUND showing the field of operations of the expedition; and on this page a MAP OF ROANOKE ISLAND showing the position of the rebel batteries.

A very neat and comprehensive report of the operations of the combined fleet and army is given in General Burnside’s Report, as follows:

Headquarters, Department of North Carolina,

Roanoke Island, Feb. 10, 1862.

To Major-General George B. McClellan, Commanding United States Army, Washington:

General, – I have the honor to report that a combined attack upon this island was commenced on the morning of the 7th by the naval and military forces of this expedition, which has resulted in the capture of six forts, forty guns, over two thousand prisoners, and upward of three thousand small arms.

Among the prisoners are Colonel Shaw, commander of the island, and O. Jennings Wise, commander of the Wise Legion. The latter was mortally wounded, and has since died.

The whole work was finished on the afternoon of the 8th inst., after a hard day’s fighting, by a brilliant charge in the centre of the island, and a rapid pursuit of the enemy to the north end of the island, resulting in the capture of the prisoners mentioned above.

We have had no time to count them, but the number is estimated at nearly three thousand.

Our men fought bravely, and have endured most manfully the hardships incident to fighting through swamps and dense thickets.

It is impossible to give the details of the engagement, or to mention meritorious officers and men in the short time allowed for writing this report, the naval vessel carrying it starting immediately for Hampton Reads, and the reports of the Brigadier-Generals having not yet been handed in. It is enough to say that the officers and men of both arms of the service have fought gallantly, and the plans agreed upon before leaving Hatteras were carried out.

I will be excused for saying in reference to the action that I owe every thing to Generals Foster, Reno, and Parks, as more full details will show.

I am sorry to report the loss of about thirty-five killed, and about two hundred wounded, ten of these probably mortally. Among the killed are Colonel Russell, of the Tenth Connecticut regiment, and Lieutenant-Colonel Victor de Monteil, of the D’Epineuil Zouaves. Both of them fought most gallantly. I regret exceedingly not being able to send a full report of the killed and wounded, but will send a dispatch in a day or two with full returns.

I beg leave to enclose a copy of a General Order issued by me on the 9th inst.

I am most happy to say that I have just received a message from Commander Goldsborough stating that the expedition of the gun-boats against Elizabeth City and the rebel fleet has been entirely successful. He will, of course, send his returns to his department.

Since then the fleet have occupied Edenton, Hertford, and have made explorations up the Chowan and Roanoke Rivers without meeting any enemy. In all probability the troops have already severed the railway connections at or near Weldon.

Capture of the Forts.

We clip the following account of the Battle at Roanoke Island from the correspondence of the Tribune:

By daybreak on the 8th, General Foster had his brigade in motion to attack the rebels, followed soon after by the brigades of Generals Reno and Parks. The advance was supported by six howitzers, commanded by Midshipmen Porter and Hammond, and manned in part from the fleet. After fording a creek, General Foster’s force came up with the enemy’s pickets, who fired their pieces and ran. Striking the main road, the brigade pushed on, and after marching a mile and a half came in sight of the enemy’s position. To properly understand its great strength, in addition to what skillful engineering had done, the reader will bear in mind that the island, which is low and sandy, is cut up and dotted with marshes and lagoons. On the right and left of the enemy a morass, deemed impassable, stretched out nearly the entire width of the island.

The upper and lower part of the island being connected by the narrow neck on which the battery was situated, and across which lay the road, the battery of three guns had been located so as to rake every inch of the narrow causeway, which, for some distance, was the only approach to the work. General Foster immediately disposed his forces for attack, by placing the 25th Massachusetts, supported by the 23d Massachusetts, in line, and opened with musketry and cannon. The enemy replied hotly with artillery and infantry. While they were thus engaged, the 27th Massachusetts came up, and were ordered by General Foster to the left to the enemy in the woods, where the rebel sharpshooters were stationed. The 10th Connecticut was placed in support of the 25th Massachusetts.

General Reno now came up with his brigade, consisting of the 21st Massachusetts, 51st New York, 51st Pennsylvania, and 9th New Jersey, and pushing through the swamps and tangled undergrowth, took up a position on the right, with the view of turning the enemy. This was done with the greatest alacrity. Meanwhile the contest raged hotly in front, our men behaving gallantly, not wavering for a moment. The Massachusetts men vied with the men of Connecticut; those of New York and New Jersey courageously supporting their brethren of Pennsylvania. Our troops were gradually overcoming the difficulties which impeded their approach, and though fighting at great disadvantage, and suffering severely, were making a steady advance. Regulars were never more steady. General Burnside was near the place of landing, hurrying up the reserves, receiving reports, and, so far as practicable, giving orders.

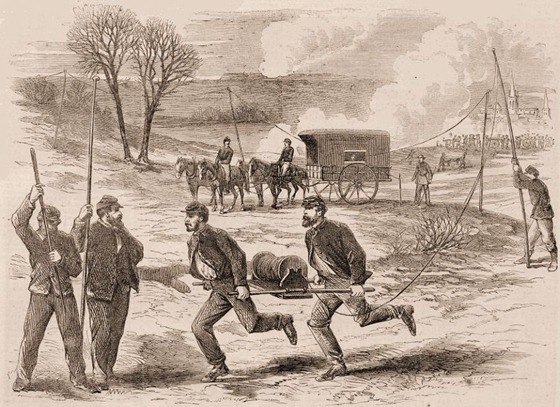

General Foster was in active command on the ground. His brave and collected manner, the skillfulness with which he, as well as General Reno and General Parks manoeuvred their forces, their example in front of the line, and their conduct in any aspect, inspired the troops to stand where even older soldiers would have wavered. In this they were seconded nobly by officers of every grade. General Parks, who had come up with the 4th Rhode Island, 8th Connecticut, and 9th New York, gave timely and gallant support to the 23d and 27th Massachusetts. The ammunition of our artillery getting short, and our men having suffered severely, a charge was the only method of dislodging the enemy. At this juncture Major Kimball, of Hawkins’s Zouaves (New York 9th) offered to lead the charge, and storm the battery with the bayonet. “You are the man, the 9th the regiment, and this the moment! Zouaves! storm the battery! Forward!” was General Foster’s reply. They started on the run, yelling like devils, cheered by our forces on every side. Colonel Hawkins, who was leading two companies in the flank movement, joined his regiment on the way. On they went, with fixed bayonets, shouting “Zou! Zou! Zou!” into the battery, cheered more loudly than ever. The rebels, taking fright as the Zouaves started, went out when they went in, leaving pretty much every thing behind them, not even stopping to spike their guns, or take away their dead and wounded that had not been removed.

General Foster immediately reformed his brigade, while General Reno, with the 21st Massachusetts and 9th New York, went in pursuit. Following in quick time, General Foster overtook General Reno; who had halted to make a movement to cut off the retreat of a body of rebels, numbering between 800 and 1000 on the left, near Wier’s Point, and not far from the upper battery. Taking a part of his force, General Reno pushed on in that direction. It being understood that there was a two-gun battery near Shellbag Bay, Colonel Hawkins, with his Zouaves, was dispatched in that direction.

General Foster pushed on at a double-quick with the 24th Massachusetts, followed by an adequate force, in the tracks of the rebels, who, panic-stricken, were fleeing at the top of their speed, throwing away as they went guns, equipments, everything, so that the road for miles was strewn with whatever the fugitives could disencumber themselves of. Thus was the pursuit kept up for more than five or six miles, when General Foster, as he was close on the heels of the enemy, was met by a flag of truce borne by Colonel Pool of the 8th North Carolina, with a message from Colonel Shaw of the North Carolina forces, and now senior in command, asking what terms of capitulation would be granted. “No longer than will enable you to report to your senior.” Colonel Pool retired, and, after waiting for what he supposed was a sufficient length of time without a replay, General Foster commenced closing on the enemy, when Major Stevenson of the 24th Massachusetts, who had gone with Colonel Pool to receive Colonel Shaw’s answer, appeared with a message that General Foster’s terms were accepted.

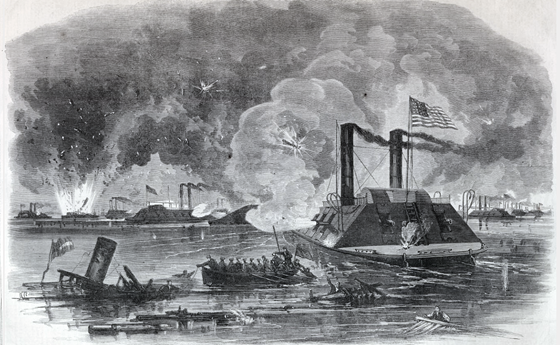

Destruction of the Rebel Fleet

The destruction of the rebel fleet by Commander Rowan is thus described by the same correspondent:

We came in sight of Elizabeth City about eight o’clock, and as we approached we discovered the enemy’s steamers – seven in number – in line of battle, in front of the city, ready to receive us. A fort was also discovered on a point which projected out some considerable distance – one-fourth of a mile, perhaps – in front of the rebel line of steamers; and directly opposite of this fort was a schooner, anchored, on which were two heavy rifle guns, the distance between the fort and this schooner being about half a mile. Four large guns were mounted on the fort, and it was thought by the rebels that no fleet of ours could pass this narrow channel; consequently they considered themselves safe, with the assistance of their navy, drawn up between the city and the fort.

At the sight of the enemy every thing was in readiness for battle. To describe the wild delight of our brave bluejackets when they first discovered the enemy is more than the pen can do.

The charge was short and desperate, and, without any exception, is one of the most brilliant ever made by the American Navy. All eyes were on the Commander, Rowan, to see what the first order would be, as we were rapidly approaching the foe.

In due time he ran up the signal to engage the enemy in close action, hand to hand. We were then about two miles from the enemy. This was a signal for a test of speed as well as a signal for a deadly encounter with a desperate foe, whose all was staked upon this final engagement. For a distance of two miles it was a race between our steamers in their eagerness to outstrip each other, and be the first to meet the enemy of the Republic face to face.

The river began to narrow as we approached the city. The point where the fort was situated necessarily brought our steamers nearer together, making them sure marks for the enemy’s guns; indeed, it would be a miracle if a shot from one of the enemy’s guns did not strike some one of our steamers. Under the circumstances, most any other commander would have thought it advisable to first attack the fort and silence the guns on both sides of that narrow point, and then attack the rebel steamers; but not so with the brave and intrepid Rowan, whose motto is to charge bayonets on the enemy whenever and wherever he may be found. In action the position of the commander’s ship is in the centre of the squadron. The Delaware, Captain Rowan’s flag-ship, was at the head of the advancing column and led the van. No attention was paid to the fort or armed schooner, as they dashed by them through a perfect torrent of shells and grape, boarded the rebel steamers, and engaged them at the point of the bayonet, as the panic-stricken rebels leaped into the water in every direction. Many were killed by the bayonet and revolver in this hand-to-hand fight, and sank below the water. Their real loss will doubtless never be known to us; the slaughter, however, was fearful, and the struggle short and desperate – not more than fifteen minutes in duration.

The fort and armed schooner were deserted quite as soon as were the rebel steamers; for it was made quite as hot work for those behind the guns as it was for their confederates on the gun-boats. Our loss is two killed and about a dozed wounded – all seamen. The death-struggle was brief. In less time than it would take to write a telegraphic dispatch the victory was ours.

The Commodore Perry was in the advance, and made for the rebel steamer Sea-Bird, the flagship of the rebel navy, on which was Commodore Lynch, and run her down, cutting her through. The Ceres ran straight into the rebel steamer Ellis, and run her down in like manner, boarding her at the same time. The Underwriter took the Forrest in the same style; while the Delaware took the Fanny in fine shape, she having received ten shots from our squadron, which made daylight through her in as many places. The Morse, Shawsheen, Lockwood, Hetzell, Valley City, Putnam, Whitehead, Blinker, and Seymour also covered themselves with glory. Every officer and man in our entire squadron behaved like a hero, one as brave as the other, all through this desperate charge. The terrified rebels, as they forsook their gun-boats, fired them, and thus all but the Ellis were burned, including a new one on the stocks. Four were burned, one captured, and two made their escape – the Raleigh and Beaufort. They are in the canal which leads to Norfolk, but are not able to go through, on account of the locks having been destroyed; consequently they will be captured before this reaches you, as they can go only some few miles toward Norfolk.