February 17th, 1866.—The house party is a thing of the past and will be long remembered. The Sprague girls, Maggie and Mary, (Tudie seems to be her name to her intimates), are such nice, pleasant young ladies. When I had known them a few days I said I would not have imagined they were from the North. They laughed and said they had been almost raised in the South. I like them very much.

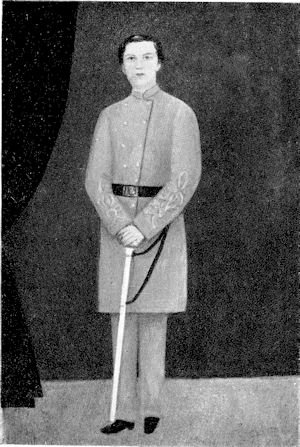

Mrs. Reed, to quote from my black mammy, “Ain’t my sort,” and I have never been thrown with one of her kind before. Mrs. Miller is a sweet old lady, a South Carolinian by birth, who married a Northern man. Her invalid son, Lieutenant Charles Miller, excited my pity to such an extent that I have tried to forget his blue uniform and remember only that he suffers. I think the almost constant contact with the sick and wounded soldiers in our own army has automatically made me tender of those who are ill. His mother watches over him day and night. Aunt Sue is just as good to them both as if they were kinsfolk and, though Uncle Arvah is such a busy man, he does all he can to lighten her burden. She was very glad to have a little help in filling in his lonely hours.

I look at it in this way; I am trying to be of some assistance to dear aunt Sue and if she wants me to read to and talk to, this poor, sick boy, it is my duty to do it. So, for a while, each morning, after his breakfast tray has been brought down stairs, I relieve his mother and, while I read some entertaining book, or glean the freshest news from the papers, she walks out among the flowers, or chats with the other guests.

Our own boys tease me about my “sick Yankee,” but I think it is right or I would not do it. He, poor fellow, is grateful; I told him doctors did not know everything, even the wisest of them. I told him I was supposed to have consumption, of which Drs. Clark and Geddings were quite positive, but I would not listen to them. My doctor Brother did not agree with them and he says, “help yourself to get well; do not think of the disease but fill your mind with bright thoughts and, if possible find something for your hands to do; live in the open and hope, Hope, HOPE.”

He was much interested in this and, the next day, instead of lying on the couch in his mother’s room, as he had done, he came down stairs, with Frank and Jack assisting him, and sat in the large cushioned rocker in the hall.

The young people in the house came about his chair and Aunt Sue said he was holding a reception. He enjoyed it until he got tired, and his mother was delighted that he had made the effort. Poor boy! He has hemorrhages but I used to have them, too, and I have quite made up my mind to live to be a hundred; if I can. [click to continue…]