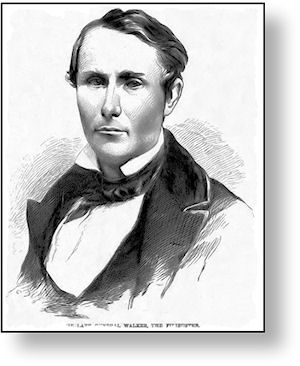

We publish herewith, as matter of history, the portrait of the famous filibuster Walker, who was executed in Honduras on 12th ult. His life had been eventful and romantic.

He was only thirty-six years old when he died. Born at Nashville, Tennessee, in 1824, he was bred a lawyer: his father, a Scotch banker, occupied a prominent position in society, and enjoyed the respect of the community in which he lived. The son was a scape-grace. He failed as a lawyer; tried medicine, and achieved no particular success in that profession; finally fell back on the press, and so, in 1851, at the dawn of civilization on the Pacific slopes, he looms up as the editor of a paper at San Francisco.

It seems likely that the unsettled and turbulent temper of the people with whom he lived shaped the uncertain aspirations of William Walker. He had not been very long in California, and was doing a good business, when he suddenly crossed the frontier, and, squatting on some unoccupied land in Northern Mexico, proclaimed “an independent Republic of Lower California.” This farce did not last long. There was a stir among the Mexican authorities, and an appearance of vigilance among the United States troops; but the point of the struggle was that the “independent Republic” and her newly-constituted rulers had nothing to eat. Walker surrendered himself and his party to a revenue officer of the United States, went through the form of a trial, and was promptly acquitted. At that day filibusterism was all the rage.

Not cured by experience, but rather encouraged by the sympathy his not very glorious exploits had won, Walker two years afterward undertook his second filibustering affray. The Democrats of Nicaragua offered him twenty thousand acres of land to fight on their side against the aristocratic party. A similar offer led Sir De Lacy Evans to fight against the Carliats in Spain, General Guyon to take a command in the Hungarian army of independence, Lord Cochrane to take a leading command in South America; Lafayette and Steuben fought for less in the United States, General Church was- satisfied with less in Greece, Colonel Upton in Russia. General Walker made some further stipulations on behalf of his men, then chartered his vessel.

Five years ago last May that vessel, the Vesta, lay in the harbor of San Francisco, with General Walker and fifty-six men on board. She was under seizure. A deputy-sheriff”s officer had possession. At midnight on Monday, the 4th May, Walker requested the sheriff’s officer to step below to examine some documents in the cabin. The unsuspecting official complied. The door shut, he was informed that he was a prisoner.

“There, Sir,” said Walker, in a slow, drawling voice, “are cigars and Champagne; and there are handcuffs and irons. Pray take your choice.”

The deputy, a sensible man, took the former, and was in a very happy frame of mind when he was put on board the steam-tug to be taken back to the scene of his official duties. In the month of June General Walker arrived in Nicaragua. The Serviles were prepared in force to resist him; he fought a battle every three weeks. The capture of Granada was quickly followed by the massacre at Virgin Bay, and the necessary inauguration of General Walker’s power in Nicaragua.

In the course of a short while a treaty of peace was signed between the contending forces; a native named Patricio Rivas was appointed President, and Walker General-in-chief of the army. This was the culminating moment of Walker’s career. He held the real power in the Government of Nicaragua, Rivas being simply his tool. He had a fine transit route in full operation, which brought him hundreds of immigrants every month. Great Britain and the United States, sick of the unsuccessful endeavors of the Spanish Americans to establish stable governments, were both ready to recognize and support him. In this country especially everyone was in his favor; he could have obtained money and men to any extent on a mere requisition. Finally, there is reason to believe that the best people in Nicaragua were fascinated by his brilliant success, and really believed that he was destined to be the regenerator of their country.

All this fair edifice of present power and future prospects Walker now proceeded deliberately to destroy. He shot Corral, his old foe, the head of the Serviles—a Central American gentleman of high standing—charging him with having plotted against the government they had combined together to establish. He revoked, without cause, the transit grant to the Nicaragua Company, and seized steamers belonging to American citizens, thus shutting himself and his new country out from the world, and closing the door to immigration. He made war upon Costa Rica, and managed matters so badly that his troops were beaten at the first encounter. Ho lost patience with Rivas, dismissed him, and usurped the Presidency. From that moment to the close of the Nicaraguan campaign his history was one of defeat, disaster, disappointment, and distress. The Nicaraguans and Costa Ricans combined against him; drove him from place to place, and at last so beleaguered him that, had it not been for the presence of an American sloop of war, which received him and his followers on board, he must have perished then and there. So ended the second filibustering expedition of Walker.

The third and fourth expeditions, both directed against Nicaragua, may be briefly disposed of. They were both ill-advised, and ill-planned; they both failed miserably; both would have terminated fatally for Walker and his followers but for the kindly interference of American and British vessels of war.

Walker’s fifth and last filibustering raid was originally intended to be prosecuted against the famous Bay Islands which Great Britain is just ceding to Honduras. Several Anglo-Saxon residents of the islands had expressed unwillingness to be handed back to Honduras; Walker saw the opportunity of erecting a new independent empire. Unfortunately for him; Honduras foresaw his game, and requested Great Britain to delay the cession of the islands. Thus disappointed, Walker cruised about in the Bay of Honduras for some weeks, literally seeking what he might devour, and finally, to his ruin, fell upon Truxillo. Forced to evacuate this place by the British war vessel Icarus, he was chased to bay by the Hondurenos; and refusing to claim either British or American protection, lie died the death of a soldier at the hands of the Honduras authorities. The details of his execution will be found in the news columns.

Walker was undoubtedly a mischievous man, better out of the world than in it. He never displayed any constructive ability; his energies were wholly destructive. He was brave, persevering, and energetic; but he had little or no foresight, no compunctions of honor or conscience, and not a spark of human pity in his breast. His works, from first to last, have been injurious rather than beneficial to the world.