A correspondent thus describes the funeral of a soldier on one of the main regiments at sea:

”Imagine a crowded transport steamer homeward bound from the war, with her human freight of sick and wounded, of officers returning on leave for a brief respite from Southern miasma and camp toil, of poor, enfeebled man dragging themselves home to die.

”The lamps are lit in the long upper saloon. Though the vessel heaves and strains in the wild, angry sea, they shine pleasantly on the little groups which surround the card tables, gather round some veteran storyteller, or chat eagerly as they anticipate, in imagination, their safe arrival and welcome home. All seems bright and cheerful. There is a little stir, a sudden interruption, a poor soldier, himself an invalid, as his sunken cheeks and hollow yet brilliant eyes but too clearly indicate, enters and asks eagerly for physician – his comrade is dying. A little party, of whom the writer is one, detach themselves from the light and noisy gaiety of the comfortable upper cabin and go down into the hold which is been roughly fitted up for human habitation. It reeks with smells; it is dimly lighted by swinging lanterns, which rock to and fro, keeping time, pendulum-like, to the roll of the sea.

”This sounds with salute the ear are in keeping with the same. Here a smothered groan, an impatient murmur, a weary sigh, the heavy monotonous clang of the ever moving machinery, mingle strangely with the dull swash of waves as they glide by, or break angrily beneath our counter, making mournful music. The man lead us on to the darkest, dreariest corner. He passes by a miserable bunk, where, upon a blanket, with his knapsack for a pillow, like something that, in the dim, uncertain light, takes human shape and form.

’Bring a lantern here,’ says the doctor. A light which had hitherto hung against the distant bulkhead, is brought. It reveals a filthy, foul-smelling resting-place, on which lies stretched a young soldier, yet in the agonies of dissolution. The rattle is already in his throat. I take the cold hand in mine, the pulse just flutters – that is all– the extremities are already chill in death. He swallows a little stimulant, but in the lingering disease (chronic diarrhea) has already done it’s wasting work. His comrade leans over and strives to rouse him. He shouts ‘Charlie! Charlie!’ But the words follow upon an ear already deaf to all earthly sounds.

”I think to myself how many times has he heard that name in his far-off New England home, from a mother’s, a sister’s, it may be yet dearer lips. And now the broad chest heaves convulsively, the face is distorted and drawn in its death agony. The eyes are opened and closed again. They will look no more upon the sunlight; they are sealed, to open up on the resurrection. There is a shudder, a contraction and expansion of the lambs, the jaw drops, a ghastly hue overspreads the face – the man is dead; a soul drifts out upon the stormy wind, on its way to God alone knows whither – a unit is removed from the sum of human existence – a Union soldier, who died as patriotically as though he has fallen upon some hard-won field, has gone to his long account.

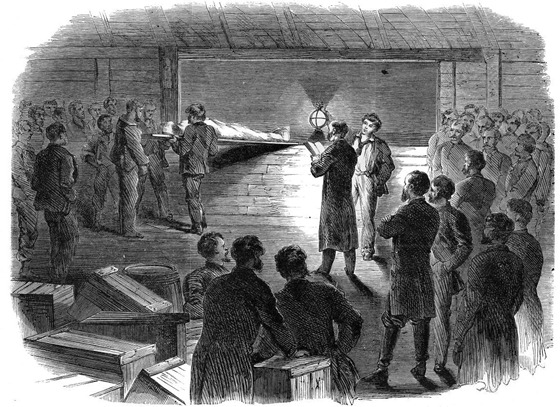

”And what a death! No one to weep over the clay; the stiffing hand held in a stranger’s grasp; the attenuated corpse rolling to and fro with each motion of the angry waves over which we ride, as it lies waiting for the speedy burial which already hastened corruption renders necessary. The body is borne forward and placed between decks. It is sewn into the camp-worn, travel stained blanket. An hour or two relapses. The chaplain and officers are called. We gather round a strange, mysterious bundle, whose rigid lines and mummy-like shape indicate what is concealed within. Every brow is bared, every utterance hushed, as the corpse, stretched upon a board and covered with the flag he died to serve, is carried to the gangway. Then come the solemn words with which the Episcopal church commits the body to the deep, ‘to be turned into corruption, looking for the general resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.’ The lanterns throw their sick sickly gleam upon the funeral rites, upon martial forms, upon the bareheaded semen, waiting to perform the last offices which mortals can render to mortality. The stars shine without, the gloomy sea heaves and tosses, the waves lift up their white fingered hands, as if pleading for their prey. There is a pause, a lifting of the shrouded clay, a dull, heavy splash, and the vessel staggers on and leaves the corpse, to lie weighted down beneath the sea into drift with the tide.

”I turn away, and go sadly back to muse over the strange burial I have witnessed. A hand touches my shoulders, I turn around. The sick soldier who had shouted ‘Charlie!’ in the dead man’s ear hands me the ‘descriptive list,’ which he has taken from the pocket of the deceased. I carry it to the light, and read, ‘Charles Myrick, of Co. A, Capt. Perry, 8th regt. Maine Volunteers, enlisted August 23, 1861, at Lowell, Maine, age 21 years.”

(Published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, February 7, 1863.)