5th. Went out with Lt. McGowan after bacon. Went 14 miles. Saw the Challes-Louise. Enjoyed seeing the family again— talkative as ever. Took some hams from Mr. Robertson’s and some others. Went to Mr. Webb’s. Got some apples. Had a good time all around. Got back to camp at ten P. M. Major cross.

Saturday, May 5, 2012

5th.—At 10 o’clock last night, I left the front line of battle, withdrew about half a mile, laid down on the ground by the side of a negro house, and about 2 this A. M., was made amusingly conscious of the fact, that underneath the eve of a roof is not a pleasant place to pillow one’s head during a heavy rain. I was not in the least thirsty. I crawled into a cellar near by, laid upon the damp brick floor, with my wet blanket over me, fell asleep and dreamed I was a “toad and fed upon the vapors of a dungeon.” But I was not a toad, though I own up to the vapors a little in the morning.

Detached from my regiment this morning to establish and organize a large army hospital at Whittaker’s. * * * *

It has been a bloody day. A battle has been fought and our enemy driven; but we have suffered terribly. About 7 A. M., Generals Hooker and Heintzleman came upon Fort Magruder, with our left wing. The enemy came out and met us. He seemed eager for the fray, which we had supposed he was running to avoid. He seemed determined and confident in his strength and position. Falling on Sickles’ Brigade, he decimated it at once. By noon, the battle on our left wing became general. General Hooker lost twelve guns, and by three o’clock our left wing was whipped and retreating in confusion.

At this time General McClellan, who, for some reason unknown to me, had been in the rear, was coming up, and met our flying battalions. By the active aid of his staff and a large escort, he succeeded in rallying our defeated army. He ordered up reinforcements, and sent them back to the field, where, though they could not drive the enemy, they maintained their ground. They retook Hooker’s lost guns, and captured one from the enemy. General Peck’s Brigade suffered severely, but he held them to the fight. The headquarters of the army and the large hospital of which I had control, were about two miles from Fort Magruder, around which the hottest of the fight raged. Shells were frequently falling and exploding in uncomfortable proximity to us, and by 3 o’clock could be heard ominous whispers about the necessity of abandoning our quarters, preparatory to a general retreat. The greatest anxiety now prevailed as to the fate of our army. The left could not hold out much longer without further reinforcements. The center had not been engaged. I hear that a dispute arose between Generals Sumner and Heintzleman, as to their rank, and that in the confusion resulting therefrom, the centre was not brought forward, nor were any of them sent to reinforce other parts of the line. (Strange that the Commander in Chief should not be with his army in a time like this!) The enemy were sending off forces to flank our right, and should they succeed in this movement and get into our rear, our whole army must inevitably be destroyed. The right wing was weak, consisting of only two brigades of General Smith’s Division—the first composed of 5th Wisconsin, 49th Pennsylvania, 6th Maine and 43rd New York, and the third composed of the 7th Maine, 33rd, 49th and 77th New York, all volunteers, with two batteries. General Davidson, who usually commanded this third brigade, being absent, the whole was under command of General W. S. Hancock. For some reason, the third brigade had not come up, and when the enemy’s detachments of six regiments, supported by a well mounted fort, the guns of which were in easy range of our lines, attacked our right, we had only the first brigade and the two batteries to contend against them. This was the position of affairs when, at half-past three o’clock, I left the large hospital crowded full of the wounded, to go to the right wing. Up to this time I had supposed our army invincible, at least by an enemy fleeing from us, and now I was utterly astounded to find our officers clearing the roads of teams, men and everything which could impede the retreat of our army, and bodies of our artillery collecting in front of all the gorges, to check the speed of a pursuing enemy. I dashed past all these, crossed Queen’s Creek, when a short ride brought me out into a large plain, in full view of our right wing, in line of battle, just as four regiments of the enemy emerged from the woods to the extreme right of our line of skirmishers. We were outflanked!

This was the most exciting moment of my life. Our left had been whipped, our centre had been passed, the Commander in Chief not on the field, the officers in command, instead of concentrating all their energies, were quarreling about their respective ranks, and had failed to reinforce the right, which had again and again sent for support, the enemy on the point of outflanking us here, and getting in our rear, in which, if successful, our army must be cut to pieces. At this moment, five companies of the 5th Wisconsin were skirmishing in the advance. Two of these companies on the right had just opened fire on the four regiments advancing. General Hancock had just given an order to fall back; the batteries, which, were in advance of all, instead of falling back, leisurely and in order, were whipping their horses, whooping, hollering, running from the field as if chased by a thousand devils; three of the four regiments of Hancock’s brigade were falling back in obedience to the order; whilst the Fifth Wisconsin, not hearing the order, or determined not to abandon their skirmishing on the field, was continuing the fight against the immense odds of four to one. Nobly did it fight, every shot seeming to tell on the advancing foe. But just then, as if to add to the certainty of our destruction, two other regiments of the enemy emerged from the abattis on the left of this wing, and were bearing directly down on the little band so nobly fighting under such disadvantage. Between these two regiments and the fighting columns was one company of the Fifth Wisconsin, skirmishing under command of Lieutenant Walker. His quick eye told him that the only hope of salvation for our army was to prevent the uniting of these forces with those now fighting, and with his little band of sixty brave men, he boldly confronted the advancing fifteen hundred, supported by their fort, not six hundred yards off. At this critical juncture, there is a moment’s relief. Our third brigade is seen in the distance—but it is too far away to afford effective aid. Again the eye reverts, as the only hope, to the fighting battalions. Lieut. Walker is manœuvring his handful of men into fighting position under cover of a fence, from which they delivered their shot into the approaching mass with wonderful effect; but still the mass advanced, and he was seen passing along his line amid the rain and the lightning of the battle, whilst his voice was heard above its roar. Suddenly a flash along the whole fort’s front, a roar of cannon, and the shrieks of shot and shell, made my blood run cold as I saw the Lieutenant whirled into the air and disappear among the rails and rubbish. The little band fell back; the cheering voice was hushed—but for a moment. Instantly he was seen emerging from the rubbish—the voice was again heard— back rushed the little band to the fight—the two bodies of the rebel army failed to connect—the battle of Queen’s Creek was won—and the army of the Potomac was saved. But in recording the part taken by Lieutenant Walker and his brave band, I must not omit to fix permanently the heroism displayed by the main body of this regiment, who carried on the fight with the four flanking regiments of the enemy. Every man seemed most of the time to be fighting after his own plan, and on his own responsibility. The five companies skirmishing were under the general command of Lieutenant Colonel Emery, to whose firmness and coolness much of our success is to be attributed. The remaining five companies were in line under Colonel Amasa Cobb. The fight was commenced on our skirmishers,[1] who slowly fell back, contesting every inch of ground till they reached their supports, who now joined in the fight, slowly falling back to the main line. The relative positions of the 5th Wisconsin, the enemy’s advancing line, and our regiments which had fallen back on the order of Gen. Hancock, were such as to prevent the rear regiments from aiding the 5th Wisconsin. It was precisely between them and the enemy, and a fire from them would have been destructive to our own men. Why Gen. Hancock did not change their position, I cannot imagine, unless under the excitement, he forgot it. To me his sole object seemed to be to get the Wisconsin regiment out of danger. The enemy were pressing it. It was sending its vollies with the deliberation and precision of marksmen at a shooting match, and at every one, the ranks of the enemy were literally mowed down. It still fell back towards the main line, firing and fighting. By the time that it reached this line the enemy’s ranks were so thinned that our success was now certain. It reached the main body, and one volley from our entire brigade ended the fight. At this moment, an order to “charge ” was given, but simultaneously with the order, the enemy displayed a white flag, and the order was countermanded. No charge was made, the firing instantly ceased, the battle was won. In twenty-one minutes from the time that the firing commenced, these four regiments were so utterly destroyed that the two regiments which Lieutenant Walker had held in check, saw the futility of a further endeavor to reach them in time, and they, too, fell back. They left in dead and wounded about seven hundred on the field. The main body of the enemy, which had been so severely punishing our left, seeing our right driving their friends, fell back on Williamsburg, leaving their dead and wounded, their fortifications, and the field in our possession. Thus ended the great battle of Williamsburg, including the battle of Queen’s Creek. The loss has been heavy on both sides, but the extent of it has not yet been ascertained.

After the battle closed, I spent the evening and night in caring for the wounded of my regiment, for whom I organized a separate hospital, keeping charge of them myself. I had seen so much indiscriminate amputating of limbs, that I determined it should not be so in my regiment, so long as it could be avoided by any efforts of mine.

[1] In this skirmishing, the companies of Captains Wheeler, Evans, Bugh, and Catlin, were engaged. Every officer, as well as every soldier, proved himself a hero.

Eliza’s Journal.

Eliza’s Journal.

On the York River, May 5.

Before we were up this morning, though that was very early, the army fleet (including Joe’s transport) was off up York river to cut off the retreat of the rebels. Our last load of sick came on board the Webster this morning early, and by nine o’clock she was ready to sail for the North, so G. and I, with Messrs. Knapp and Olmsted, and our two doctors, Wheelock and Haight, were transferred by the Wilson Small to the great “Ocean Queen,” lying in the bay. We sailed up to Yorktown, standing on deck in the rain to enjoy the approach to the famous entrenchments. Gloucester Point alone, with its beautiful little sodded fort, looked very formidable, and the works about Yorktown are said to be almost impregnable. The rebels left fifty heavy guns behind them and much baggage, camp equipage, etc.

“…a mighty poor showing for the first attempt of this army.”–“The truth is that none of them has had any experience with large bodies of men and must learn by actual experience…”.–Diary of Josiah Marshall Favill.

May 5th. The drums beat reveille at daybreak, when about four hundred men fell in, the bulk of them having straggled in during the night. They were in a sorry plight, wet through and covered with mud from head to foot. As soon as the roll was called, the men were ordered to prepare breakfast, and immediately afterwards marched forward with the rest of the brigade. I was ordered to remain behind, collect the stragglers as they came along, and when all were up, march them forward to join the colonel in decent order. So when everybody had gone, I posted a man in the road to intercept the men as they came along, and then rode over to a farm house to get something to eat for my horse, as he had not been fed since the previous morning. By ten o’clock, nearly two hundred men having reported, pretty much all that were missing, we marched out in good order and joined the colonel about two o’clock. The regiments of our brigade were in bivouac, resting from their heavy march, enjoying the sunshine which was fast drying up the fields and roads. They gave us a hearty welcome as we came on the ground, and the colonel seemed glad to get the regiment together again. Lieutenant Broome, acting quartermaster in place of McKibbin, sick in hospital, soon afterwards came up in charge of the wagons with full supplies, and so we were all in good humor again. Stoneman with his cavalry caught up with Stuart’s cavalry at the half-way house yesterday and skirmished with them as far as the rebel line of earthworks at Williamsburg, where quite a little fight took place, our men finally withdrawing to await the arrival of the infantry. Hooker and Smith, each in command of his respective division, hurried to the support of the cavalry; Hooker by the route we followed, Smith by a road from Dam No. 1, running by Lee’s mills, which brought him up on our left. Kearny, Couch and Casey followed, we coming last. General Sumner, who is second in command, was sent to the front to assume command, by direction of General McClellan, who remained in Yorktown, we are told, for the purpose of shipping Franklin’s division and Porter’s corps up the York river to West Point to intercept the enemy’s retreat. As soon as Hooker came upon the field he opened the engagement with his own division, without orders from Sumner and without any knowledge of Smith’s whereabouts and succeeded at first in driving the enemy back and capturing some earthworks, but shortly afterwards, when the rebels brought up reinforcements, he was driven back in considerable disorder, losing two of his batteries. About noon of the 5th, he was badly beaten, but luckily for him, Kearny came up just in time, recovering the abandoned batteries and all the ground lost by Hooker during the morning, when darkness put an end to the fighting. In the meantime, Sumner arranged for a general combined attack. There were several unoccupied redoubts that the enemy had built here, and Hancock was sent with his own and another brigade and a battery to occupy them. Hancock took possession, garrisoned the redoubts, and throwing out a line of skirmishers found and took possession of several other works in front of him. The rebels were so fully occupied with the attack made by Hooker that they had entirely neglected their left, and when they found the redoubts in our hands were greatly astonished. A strong infantry force came up to drive Hancock out, forming just at the edge of the woods. Hancock’s command opened upon them when within range and supported by the fire of the redoubts soon threw them into disorder, finally charging them in splendid style, and capturing about four hundred. Amongst the wounded was General Early and several other officers. About four hundred men were killed outright. At night the situation was about the same as at the opening, Hancock holding what he had occupied without resistance, at first, and Kearny occupying the ground Hooker had been driven from early in the day; on the whole it was a failure on our part to make any decided impression, as we ought to have done. About five o’clock in the evening McClellan came on the ground and was loudly cheered. He was disappointed with the management of affairs and came up to arrange for a combined movement the next morning, but during the night the enemy abandoned Williamsburg and got away. We were immediately ordered back to Yorktown to take transports for West Point. It is reported that our loss is over two thousand men killed, wounded, and missing, and five guns, a mighty poor showing for the first attempt of this army. Thus ended the siege of Yorktown without our division firing a shot; every one is criticising every one else, of course. Heintzleman and Sumner are at loggerheads, and all the general officers are united only in disparaging each other. They are so dreadfully jealous that a combined and earnest attack seems almost impossible. The truth is that none of them has had any experience with large bodies of men and must learn by actual experience, as well as the private soldier; until they have done this, we are not likely to have any great success.

May 5.—Mrs. Ogden is here with four Mobile ladies; the others have returned to their homes. The ladies who are with her are Mrs. May, Miss Wolf, Miss Murphy, and Mrs. Millward. They are on their way to Rienzi to attend the patients. I am glad that they are going, as they will be the means of doing much good.

We have a boy here, named Sloan, from Texas, and a member of the Texas Rangers. He is only thirteen years of age, and lost a leg in a skirmish. He is as happy as if nothing was the matter, and he was at home playing with his brothers and sisters. His father is with him, and is quite proud that his young son has distinguished himself to such a degree, and is very grateful to the ladies for the kind attention which they bestow upon him.

A few days ago a number of wounded men were brought in. In going round, as usual, to see if I knew any one, I saw a man who seemed to have suffered a great deal. His eyes were closed, and while I was looking at him he opened them, and said, with a feeble voice, “Is not this a cruel war.” I requested him to keep quiet. As I left him, a gentleman approached me and remarked, “I see that you have been talking to my friend. He is going to die, and we can ill spare such men. He is one of the bravest and best men in the army.” He informed me that his name was Smith, and at the time of the fight was acting quartermaster of the Twenty-fifth Tennessee Regiment, and that he was also a Methodist minister. After I had given him a cup of tea, I asked one of the surgeons what he thought of his condition. He replied that I could do what I pleased for him as he could not possibly live more than twenty-four hours. After he was shot, he carried a wounded man off the battlefield. He himself was then placed on horseback. The horse, being wild, threw him. He was then placed in a wagon, and carried some four or five miles, over an extremely rough road. From all this he lost much blood. Notwithstanding the opinion of the surgeons, he is improving.

I have just received a box of “good things” for the patients from the kind people of Mobile. My friend, Mr. McLean, has sent his share. I am so grateful for them. If they only knew or could realize one half the suffering that we daily witness, they would do more.

Poor Mr. Jones, the young lad whom Miss Henderson is attending, has had a leg amputated to-day. He conversed very calmly about it before it was done, and seemed to think that he would not survive the operation. He has told Miss H. all about his people, and what she must tell them if he should die. She has nursed him as carefully as if she had been his own sister. He loved to have some of us read the Bible to him.

We have no chaplain to attend the sick and dying men; they often ask for one. I have thought much of this, and wonder why chaplains are not appointed for the hospitals. I think that if there is one place more than another where they should be, it is one like this; not for the dying alone, but for the moral influence it would exert upon the living. We profess to be a Christian people, and should see that all the benefits of Christianity are administered to our dying soldiers.

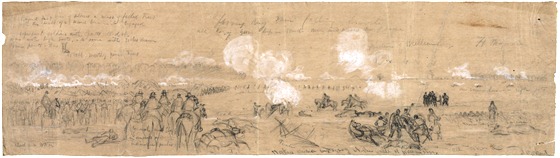

A gloomy day at Williamsburg, rain falling heavily, all hazy, May 5, 1862

Drawn by Alfred R. Waud.

- Signed lower right: A.R. Waud.

- Title inscribed below image.

- Inscribed upper left: Beyond first line of soldiers a mass of felled trees while the heads of a second line in it engaged. Represent soldiers with pants rolled up some with high boots, and some with socks drawn over pants thus. Inscribed within image as indicators: Woods mostly pine trees; Gloomy day rain falling heavily. all hazy. Guns deep in mud. Men and horses same; Mud and water; General and Staff in overcoats and india rubber ponchos; all mud; fences; direction of Williamsburg; our skirmishers in rifle pits; men laying down; Ft. Magruder; Road; Skirmishers.

- Published in: Harper’s Weekly, May 24, 1862, p. 332.

- Gift, J.P. Morgan, 1919 (DLC/PP-1919:R1.2.759)

Part of Morgan collection of Civil War drawings. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Record page for this drawing: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004660492/

May 5th, 1862.—We are continually hearing rumors of a fierce battle at Williamsburg but we do not know on what these rumors are based; we have no telegraphic communication and for weeks the mails have been so irregular as to amount to no news at all. No letters; no passing; just no news at all that can be relied on. We can only hope and pray.

May 5.— H. M. Rector, Governor of Arkansas, called upon the people of that State by proclamation to take up arms and drive out the “Northern troops.”—(Doc. 6.)

— This day the battle of Williamsburgh was fought between the Union forces in the advance toward Richmond, and a superior force of the rebel army under Gen. J. E. Johnston. The Nationals were assailed with great impetuosity at about eight A.M. The battle continued till dark. The enemy was beaten along the whole line and resumed his retreat under cover of the night— (Docs. 7 and 96.)

— General Butler promised to Louisiana planters that all cargoes of cotton or sugar sent to New-Orleans for shipment should be protected by the United States forces.—National Intelligencer, May 30.

— Last night, Lieutenant Caldwell, of the light artillery, received information of the return to his home in Andrew County, Missouri, of the notorious Captain Jack Edmundson. For some months past Edmundson had been with the rebel army in Southern Missouri and Arkansas, but had now returned, as was supposed, for the purpose of raising a guerrilla company, stealing a lot of cattle and making off with them.

Lieutenant Caldwell at once proceeded to headquarters at Saint Joseph’s, and obtained an order to take a sufficient force, and proceed in pursuit of Edmundson and his gang. No time was lost, and the party arrived at the house of the guerrilla just before daybreak. But by some means Edmundson had been informed of their approach, or was on the look-out, and escaped from the house just as the party approached. He was pursued, and so hot was the pursuit, that he dropped his blanket and sword, but reaching some thick brush, managed to escape. The party then proceeded to other parts of Andrew and Gentry Counties, and arrested some twenty men whom Edmundson had recruited for his gang. They were all carried to Saint Joseph’s and confined. —St. Joseph’s Journal, May 8.

— General Dumont, with portions of Woodford’s and Smith’s Kentucky cavalry, and Wynkoop’s Pennsylvania cavalry, attacked eight hundred of Morgan’s and Woods’s rebel cavalry at Lebanon, Kentucky, and after an hour’s fight completely routed them.—(Doc. 22.)

— D. B. Lathrop, operator on the United States military telegraph, died at Washington, D. C, from injuries received by the explosion of a torpedo, placed by the rebels in the deserted telegraph-office at Yorktown, Va.

—The rebel guerrilla, Jeff. Thompson, attacked and dispersed a company of Union cavalry near Dresden, Ky.