May 30.—The army of the South-West, under Major-Gen. Halleck, occupied Corinth, Miss., it having been evacuated by the rebels last night— (Docs. 50 and 95.)

—This morning the rebels opened fire from one of their pieces, situated on a hill at the left of the road that approaches Mechanicsville, Va., from Chickahominy Bridge, directing it toward the Fifth Vermont regiment, which had been sent out to do picket-duty. The regiment advanced into an open field, thereby exposing themselves to the rebels, but retired into the woods before any casualties had occurred, after a few rounds of shell had been dropped among them.

—Judge James H. Bircch, candidate for Governor of Missouri, was arrested at Rolla, in that State, by order of Col. Boyd, “for uttering disloyal sentiments, while making a speech, which was evidently designed to procure secession votes.”

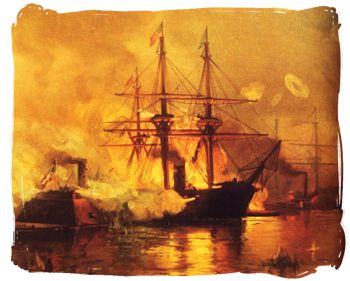

—The English iron steamer Cambria arrived at Philadelphia, Pa., having been captured by the United States gunboat Huron, after a chase of five hours, off Charleston, S. C. She hails from Carlisle, and sailed from Liverpool for Nassau, and thence for Charleston. Her cargo consisted of liquors, cloths, medicines, Enfield rifles, saltpetre, etc.

—The Thirteenth and Forty-seventh regiments, of Brooklyn, and the Sixty-ninth regiment, of New-York City, left for the seat of war.

—The rebel forces, under Gen. Jackson, made an attempt to dislodge the National forces at Harper’s Ferry, but were repulsed.—(Doc. 62.)

—A Brigade of National troops, preceded by four companies of the Rhode Island cavalry, entered Front Royal, Va., this morning, and drove out the rebels, consisting of the Eighth Louisiana, four companies of the Twelfth Georgia, and a body of cavalry. They were taken completely by surprise, and had no time either to save or to destroy any thing. A large amount of transportation fell into the hands of the Nationals, including two engines and eleven cars of the Manassas Gap Railroad, and they captured six officers and one hundred and fifty privates, besides killing and wounding a large number of rebels. The Union loss was eight killed, five wounded, and one missing. Several of the Union men who were taken prisoners at Front Royal a week ago were recaptured.

—Thirteen members of the Eleventh Pennsylvania volunteer cavalry were captured near Zuni, Va., this day.—Petersburgh Express, June 2.

29th.—No official accounts from “Stonewall” and his glorious army, but private accounts are most cheering. In the mean time, the hospitals in and around Richmond are being cleaned, aired, etc., preparatory to the anticipated battles. Oh, it is sickening to know that these preparations are necessary! Every man who is able has gone to his regiment. Country people are sending in all manner of things—shirts, drawers, socks, etc., hams, flour, fresh vegetables, fruits, preserves—for the sick and wounded. It is wonderful how these things can be spared. I suppose, if the truth were known, that they cannot be spared, except that every man and woman is ready to give up every article which is not absolutely necessary; and I dare say that gentlemen’s wardrobes, which were wont to be numbered by dozens, are now reduced to couples.

29th.—No official accounts from “Stonewall” and his glorious army, but private accounts are most cheering. In the mean time, the hospitals in and around Richmond are being cleaned, aired, etc., preparatory to the anticipated battles. Oh, it is sickening to know that these preparations are necessary! Every man who is able has gone to his regiment. Country people are sending in all manner of things—shirts, drawers, socks, etc., hams, flour, fresh vegetables, fruits, preserves—for the sick and wounded. It is wonderful how these things can be spared. I suppose, if the truth were known, that they cannot be spared, except that every man and woman is ready to give up every article which is not absolutely necessary; and I dare say that gentlemen’s wardrobes, which were wont to be numbered by dozens, are now reduced to couples.

May 29. [Okolona, Mississippi]—In company with a lady, I visited the General Hospital. Dr. Caldwell has improved much since my last visit here, as he granted us permission to go through it, and has condescended to have one lady—Mrs. Woodall—in his hospital. I was introduced to her, and tendered my services, but she did not accept them. I should not think that it was possible for her to do one third part of the work necessary. I am told that there are no less than two thousand patients in the place.

May 29. [Okolona, Mississippi]—In company with a lady, I visited the General Hospital. Dr. Caldwell has improved much since my last visit here, as he granted us permission to go through it, and has condescended to have one lady—Mrs. Woodall—in his hospital. I was introduced to her, and tendered my services, but she did not accept them. I should not think that it was possible for her to do one third part of the work necessary. I am told that there are no less than two thousand patients in the place.