30th.—The Yankee army ravaging Stafford County dreadfully, but they do not cross the river. Burnside, with the “greatest army on the planet,” is quietly waiting and watching our little band on the opposite side. Is he afraid to venture over? His “On to Richmond” seems slow.

November 2012

November 30 — This afternoon I went through the fortifications, or rather earthworks, situated on the hills west and northwest of Winchester. The earthworks were constructed by the Yankees and are about half a mile from town, and thoroughly command the town and all the surrounding country. There are five or six separate works, all of an octagonal form, surrounded by a ditch ten feet wide and twelve feet deep. One of the works is constructed of bags filled with clay, and I suppose that there are about two hundred thousand bags in the one work. The walls are thick and built with a careful precision as to proportions and angles, and all of them are perfectly shell-proof — at least against field guns. In the center of each work is an earth-covered magazine for ammunition storage, and in one of the works is a cistern for water.

Sunday, 30th—We lay in camp here at Waterford all day and I wrote a letter to John Moore. I was on picket last night, but was relieved this morning. There was some skirmishing and cannonading out on the Tallahatchie river today. Several troops passed here going out to the front. The land in this part of the country is very rough and very poor. The soil is sandy and is easily worked.

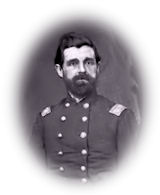

To Mrs. Lyon.

Fort Henry, Sunday evening, Nov. 30, 1862.—The last day of each month is inspection day in the army, so I have been engaged all day in making a minute and thorough inspection of my command—not only of the dress, arms, accoutrements and appearance of the men, but of their tents, kitchens, cook-houses, shanties, cooking utensils, dishes, etc. Fancy me examining tin plates, dish kettles, coffee pots, knives, forks, spoons, tin cups, and the like; threatening to send dirty cooks to the guard house, praising the clean ones, ordering alterations, suggesting improvements, etc.; in which duty I was accompanied and assisted by the Major, Adjutant and two of the surgeons; and you will have a very good idea of inspection day. I give special and constant attention to the cleanliness of the camp, and it is now one of the cleanest I ever saw and is constantly improving, for the officers and men enter most cordially into the spirit of the thing.

I am still on a general Court-Martial. It is a great bore, too, much like practicing law. The day has been warm and cloudy. This evening it rains copiously, but my tent is warm and dry and as cozy as you could wish were you here to enjoy it with me, as I trust you will be before many weeks elapse. We shall live in the most approved style. Colonel Lowe still intends an expedition after Napier.

Sunday, 30th. Had to make out morning report and field report and details. Was kept quite busy all day. In the evening wrote to Fannie A.

Lumpkin’s Mill, Miss., Sunday, Nov. 30. This was a dark and sultry morning, and about 8 A. M. while sitting upon the ground, I felt the earth shake a kind of a dull roll, which was felt by many. Firing with siege guns was commenced at about nine o’clock and kept up briskly through most of the day. While listening to the firing, expecting momentarily to be called upon, the orders came to hitch up, get two days’ rations in haversacks, and ready to march in half an hour. 11 A. M. At this time L. N. Keeler rode up for one man to go foraging. Sergeant Hamilton detailed me. We started with two teams and three men, Bowman, Leffart and myself. We went to the northeast one and one fourth miles, crossed the railroad, found our corn in an old log barn. We had to turn around before loading in order to be ready to leave in case of necessity, as the pickets close by were expecting an attack. We loaded our corn got three quarters of a barrel of salt from the smoke house and returned in a hurry. Found the Battery still there, unharnessed and cooled down. The firing gradually ceased, and by night was heard no more. We went to bed without knowing anything of the result in the front.

P. S. This place represented as Waterford proved to be called Lumpkin’s Mill.

Nov. 30. —We woke up the morning after we came aboard, — Warriner, Bias, and I. Company D woke up generally on the cabin-floor. Poor Companies H and F woke up down in the hold. What to do for breakfast? Through the hatchway opposite our stateroom-door, we could see the waiters in the lower cabin setting tables for the commissioned officers. Presently there was a steam of coffee and steaks; then a long row of shoulder-straps, and a clatter of knives and forks; we, meanwhile, breakfastless, and undergoing the torments of Tantalus.

But we cannot make out a very strong case of hardship. Beef, hard-bread, and coffee were soon ready. Bill Hilson, in a marvellous cap of pink and blue, cut up the big joints on a gun-box. The “non-coms,” whose chevrons take them past the guard amidships, went out loaded with the tin cups of the men to Hen. Hilson, — out through cabin-door, through greasy, crowded passage-way, behind the wheel, to the galley, where, over a mammoth, steaming caldron, Hen., through the vapor, pours out coffee by the pailful. Hen. looks like a beneficent genius, — one of the “Arabian Nights” sort,—just being condensed from the smoke and mist of these blessed hot kettles. He drips, and almost simmers, with perspiration, as if he had hardly gone half-way yet from vapor to flesh.

I have been down the brass-plated staircase, into the splendors of the commissioned-officers’ cabin,—really nothing great at all; but luxurious as compared with our quarters, already greasy from rations, and stained with tobacco-juice; and sumptuous beyond words, as compared with the unplaned boards and tarry odors of the quarters of the privates. Have I mentioned that now our places are assigned? The “non-coms”— noncommissioned, meaning, not non compos; though evil-minded high privates declare it might well mean that — have assigned to them an upper cabin, with staterooms, over the quarters of the officers, in the after-part of the ship. The privates are in front, on the lower decks, and in the hold. I promise, in a day or two, to play Virgil, and conduct you through the dismal circles of this Malebolge. Now I speak of the cabin of the officers. The hatches are open above and below, to the upper deck and into the hold. Down the hatch goes a dirty stream of commissary-stores, gun-carriages, rifled-cannon, and pressed hay, within an inch or two of cut-glass, gilt-mouldings, and mahogany. The third mate, with voice coarse and deep as the grating of ten-ton packages along the skids, orders this and that, or bays inarticulately in a growl at a shirking sailor.

Five sergeants of our company, and two corporals of us, have a stateroom together,—perhaps six feet by eight. Besides us, two officers’ servants consider that they have a right here. Did any one say, “Elbowroom”?

“…a decaying country finally ruined by war.”–Adams Family Letters, Charles Francis Adams, Jr., to his father.

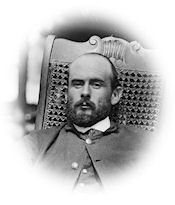

Potomac Bridge, near Falmouth, Va.

November 30, 1862

Here we are once more with the army, but not on the move. We passed six days in Washington and it stormed the whole time, varying from a heavy Scotch mist to a drenching rain. Our camp was deep in mud, at times a brook was running through my tent, and altogether we were most unfortunate as regarded weather. Still we succeeded in completing our equipment and I started out on our new campaign tolerably prepared to be comfortable in future. Nor did I, I am glad to say, waste my time while there, but I fed on the fat of the land, feasting daily, without regard to expense, at Buhler’s. I no longer wonder at sailors’ runs on shore. Months of abstinence and coarse fare, cooked anyhow and eaten anywhere off anything, certainly lead to an acute appreciation of the luxuries of city life. It seems to me now as if I could n’t enjoy them enough. While here I saw Aunt Mary repeatedly and she seems much the same as ever. She was very kind and hospitable. I also saw Governor Seward for an instant. He invited me to dinner and was very cordial; but he looks pale, old and careworn, and it distressed me to see him.

Here we remained till Friday evening, on which day the two Majors and myself succeeded in getting paid off, after immense exertion and many refusals, when we had our last dinner at Buhler’s and on Saturday, when we saw the sun for the first time for a week, we struck camp and moved over to Alexandria, on our way to join the brigade. We got into Alexandria by two o’clock and went into camp on a cold, windy hill-side. We were under orders to join our brigade at Manassas, but when we got to Alexandria we found Manassas in the possession of the enemy and we did not care to report to them. Accordingly we sent back for orders and passed Sunday in camp, a cold, blustering, raw November day, overcast and disagreeable. The damp and wet, combined with the high living at Washington, had started my previous health, and now I not only was n’t well, but was decidedly sick and lived on opium and brandy. In fact I am hardly well yet and my disorder followed me all through our coming march. Sunday afternoon we got our orders to press on and join the brigade at the earliest possible moment near Falmouth, so Monday morning we again struck camp and set forth for Falmouth. It was a very fine day indeed, but the weather is not what it was and the country through which we passed is sadly war-smitten. The sun was bright, but the long rains had reduced the roads almost to a mire and a sharp cold wind all day made overcoats pleasant and reminded us how near we were to winter. Our road lay along in sight of Mt. Vernon and was a picture of desolation — the inhabitants few, primitive and ignorant, houses deserted and going to ruin, fences down, plantations overgrown, and everything indicating a decaying country finally ruined by war. On our second day’s march we passed through Dumfries, once a flourishing town and port of entry, now the most God-forsaken village I ever saw. There were large houses with tumbled down stairways, public buildings completely in ruins, more than half the houses deserted and tumbling to pieces, not one in repair and even the inhabitants, as dirty, lazy and rough they stared at us with a sort of apathetic hate, seemed relapsing into barbarism. It maybe the season, or it may be the war; but for some reason this part of Virginia impresses me with a sense of hopeless decadence, a spiritless decay both of land and people, such as I never experienced before. The very dogs are curs and the women and children, with their long, blousy, uncombed hair, seem the proper inmates of the delapidated log cabins which they hold in common with the long-nosed, lank Virginia swine.

To go back to our march however. Our wagons toiled wearily along and sunset found us only sixteen miles from Alexandria, and there we camped. During the latter part of the day I was all alone riding to and fro between the baggage train and the column. I felt by no means well and cross with opium. It was a cold, clear, November evening, with a cold, red, western sky and, chilled through, with a prospect of only a supperless bivouac, a stronger home feeling came over me than I have often felt before, and I did sadly dwell in my imagination on the intense comfort there is in a thoroughly warm, well-lighted room and well-spread table after a long cold ride. However I got into camp before it was dark and here things were not so bad. The wind was all down, the fires were blazing and we had the elements of comfort. The soup Lou sent me supplied me with a hot supper — in fact I don’t know what I should have done if it had not been for that, through this dreary march; and after that I spread my blankets on a bed of fir-branches close to the fire and slept as serenely as man could desire to sleep.

The next morning the weather changed and it gradually grew warmer and more cloudy all day. Our road lay through Dumfries and became worse and worse as we pushed along, until after making only eight miles, we despaired of our train getting along and turned into an orchard in front of a deserted plantation house and there camped. Our wagons in fact did get stuck and passed the night two miles back on the road, while we built our fires and made haste to stretch our blankets against the rain. It rained hard all night, but we had firewood and straw in plenty, and again I slept as well as I wish to. Next day the wagons did not get up until noon and it was two o’clock before we started. Then we pushed forward until nearly dark. An hour before sunset we came up with the flank of the army resting on Acquia Creek. We floundered along through the deep red-mud roads till nearly dark and then, having made some five miles, turned into a beautiful camping ground, where we once more bivouacked. One thing surprises me very much and that is the very slight hardship and exposure of the bivouac. Except in rains tents are wholly unnecessary — articles of luxury. Here, the night before Thanksgiving and cold at that, I slept as soundly and warmly before our fire as I could have done in bed at home. The reason is plain. In a tent one, more or less, tries to undress; in the bivouac one rolls himself, boots, overcoat and all, with the cape thrown over his head, in his blankets with his feet to the fire, which keeps them warm and dry, and then the rest will not trouble him. A tent is usually equally cold and also very damp.

The next day was Thanksgiving Day — 27th November. It was a fine clear day, with a sharp chill in the little wind which was stirring. I left the column and rode forward to General Hooker’s Head Quarters through the worst roads I ever saw, in which our empty wagons could hardly make two miles an hour. I saw General Hooker and learnt the situation of our brigade, and here too we came up with our other battalion. We passed them however and came over here to our present camp, where we have pitched our tents and made ourselves as comfortable as we can while we await the course of events.

As to the future, you can judge better than I. I have no idea that a winter campaign is possible in Virginia. The mud is measured already by feet, and the rains have hardly begun. The country is thoroughly exhausted and while horses can scarcely get along alone, they can hardly succeed in drawing the immense supply and ammunition trains necessary for so large an army, to say nothing of the artillery which will be stuck fast. The country may demand activity on our part, but mud is more obdurate than popular opinion, and active operations here I cannot but consider as closed for the season. As to the army, I see little of my part of it but my own regiment. I think myself it is tired of motion and wants to go to sleep until the spring. The autumn is depressing and winter hardships are severe enough in the most comfortable of camps. Winter campaigns may be possible in Europe, a thickly peopled country of fine roads, but in this region of mud, desolation and immense distances, it is another matter.

NOVEMBER 30TH.—It is said there is more concern manifested in the government here on the indications that the States mean to organize armies of non-conscripts for their own defense, than for any demonstration of the enemy. The election of Graham Confederate States Senator in North Carolina, and of H. V. Johnson in Georgia, causes some uneasiness. These men were not original secessionists, and have been the objects of aversion, if not of proscription, by the men who secured position in the Confederate States Government. Nevertheless, they are able men, and as true to Southern independence as any. But they are opposed to despotic usurpation—and their election seems like a rebuke and condemnation of military usurpation.

From all sections of the Confederacy complaints are coming in that the military agents of the bureaus are oppressing the people; and the belief is expressed by many, that a sentiment is prevailing inimical to the government itself.

Sunday, November 30. [Chattanooga] —Called on Mrs. Newsom this afternoon; had a long talk over our hospital trials. She related some of the hospital scenes at Bowling Green, which were truly awful—Corinth was heaven in comparison. I met Major Richmond there, one of General Polk’s aids. He is a fine-looking man, and very intelligent, with all the suavity of manner characteristic of the southern gentleman. He has traveled much, and related a number of anecdotes of scenes on the continent of Europe; told some few of England and Englishmen, and seemed to judge the whole, as many others have done, both in this country and the old, by the little he had seen, a mistake we are all liable to fall into. On the whole, his conversation was very interesting.

Dr. Hunter has gone on a visit to Mississippi; Dr. Abernethy of Tennessee has taken his place. We have a nice old negro man belonging to the latter, who cooks for us. We get a good deal of money now, as the hospitals are out of debt. Some days we have as many as seven hundred patients; not more than one half of them are confined to bed.