Sunday, 2d.—All quiet to-day, preparatory to moving. Spent most of the day in calling on and receiving calls from the officers and soldiers of the regiment. All seemed glad to welcome me back. I hope and believe they were sincere. Went to church in the afternoon, but heard no sermon.

Friday, November 2, 2012

Sunday, 2d.—Moved half-mile. Brother Harvey came to see us.

Sunday, November 2d.

Yesterday was a day of novel sensations to me. First came a letter from mother announcing her determination to return home, and telling us to be ready next week. Poor mother! she wrote drearily enough of the hardships we would be obliged to undergo in the dismantled house, and of the new experience that lay before us; but n’importe! I am ready to follow her to Yankeeland, or any other place she chooses to go. It is selfish for me to be so happy here while she leads such a distasteful life in Clinton. In her postscript, though, she said she would wait a few days longer to see about the grand battle which is supposed to be impending; so our stay will be indefinitely prolonged. How thankful I am that we will really get back, though! I hardly believe it possible, however; it is too good to be believed.

The nightmare of a probable stay in Clinton being removed, I got in what the boys call a “perfect gale,” and sang all my old songs with a greater relish than I have experienced for many a long month. My heart was open to every one. So forgiving and amiable did I feel that I went downstairs to see Will Carter! I made him so angry last Tuesday that he went home in a fit of sullen rage. It seems that some time ago, some one, he said, told him such a joke on me that he had laughed all night at it. Mortified beyond all expression at the thought of having had my name mentioned between two men, I, who have thus far fancied myself secure from all remarks good, bad, or indifferent (of men), I refused to have anything to say to him until he should either explain me the joke, or, in case it was not fit to be repeated to me, until he apologized for the insult. He took two minutes to make up a lie. This was the joke, he said. Our milkman had said that that Sarah Morgan was the proudest girl he ever saw; that she walked the streets as though the earth was not good enough for her. My milkman making his remarks! I confess I was perfectly aghast with surprise, and did not conceal my contempt for the remark, or his authority either. But one can’t fight one’s milkman! I did not care for what he or any of that class could say; I was surprised to find that they thought at all! But I resented it as an insult as coming from Mr. Carter, until with tears in his eyes fairly, and in all humility, he swore that, if it had been anything that could reflect on me in the slightest degree, he would thrash the next man who mentioned my name. I was not uneasy about a milkman’s remarks, so I let it pass, after making him acknowledge that he had told me a falsehood concerning the remark which had been made. But I kept my revenge. I had but to cry “Milk!” in his hearing to make him turn crimson with rage. At last he told me that the less I said on the subject, the better it would be for me. I could not agree. “Milk” I insisted was a delightful beverage. I had always been under the impression that we owned a cow, until he had informed me it was a milkman, but was perfectly indifferent to the animal so I got the milk. With some such allusion, I could make him mad in an instant. Either a guilty conscience, or the real joke, grated harshly on him, and I possessed the power of making it still worse. Tuesday I pressed it too far. He was furious, and all the family warned me that I was making a dangerous enemy.

Yesterday he came back in a good humor, and found me in unimpaired spirits. I had not talked even of “curds,” though I had given him several hard cuts on other subjects, when an accident happened which frightened all malicious fun out of me. We were about going out after cane, and Miriam had already pulled on one of her buckskin gloves, dubbed “old sweety” from the quantity of cane-juice they contain, when Mr. Carter slipped on its mate, and held it tauntingly out to her. She tapped it with a case-knife she held, when a stream of blood shot up through the glove. A vein was cut and was bleeding profusely.

He laughed, but panic seized the women. Some brought a basin, some stood around. I ran after cobwebs, while Helen Carter held the vein and Miriam stood in silent horror, too frightened to move. It was, indeed, alarming, for no one seemed to know what to do, and the blood flowed rapidly.

Presently he turned a dreadful color, and stopped laughing. I brought a chair, while the others thrust him into it. His face grew more deathlike, his mouth trembled, his eyes rolled, his head dropped. I comprehended that these must be symptoms of fainting, a phenomenon I had never beheld. I rushed after water, and Lydia after cologne. Between us, it passed away; but for those few moments I thought it was all over with him, and trembled for Miriam. Presently he laughed again and said, “Helen, if I die, take all my negroes and money and prosecute those two girls! Don’t let them escape!” Then, seeing my long face, he commenced teasing me. “Don’t ever pretend you don’t care for me again! Here you have been unmerciful to me for months, hurting more than this cut, never sparing me once, and the moment I get scratched, it’s ‘O Mr. Carter!’ and you fly around like wild and wait on me!” In vain I represented that I would have done the same for his old lame dog, and that I did not like him a bit better; he would not believe it, but persisted that I was a humbug and that I liked him in spite of my protestations. As long as he was in danger of bleeding to death, I let him have his way; and, frightened out of teasing, spared him for the rest of the evening.

Just at what would have been twilight but for the moonshine, when he went home after the blood was stanched and the hand tightly bound, a carriage drove up to the house, and Colonel Allen was announced. I can’t say I was ever more disappointed. I had fancied him tall, handsome, and elegant; I had heard of him as a perfect fascinator, a woman-killer. Lo! a wee little man is carried in, in the arms of two others, — wounded in both legs at Baton Rouge, he has never yet been able to stand. . . . He was accompanied by a Mr. Bradford, whose assiduous attentions and boundless admiration for the Colonel struck me as unusual. . . . I had not observed him otherwise, until the General whispered, “Do you know that that is the brother of your old sweetheart?” Though the appellation was by no means merited, I recognized the one he meant. Brother to our Mr. Bradford of eighteen months ago! My astonishment was unbounded, and I alluded to it immediately. He said it was so; that his brother had often spoken to him of us, and the pleasant evenings he had spent at home.

Sunday, 2d—We struck our tents, packed our knapsacks and sent them into Corinth for storage. The sick were all left in the hospital at Corinth. We started at 2 p. m. and marched fourteen miles, when we bivouacked for the night. The roads are very dusty and the weather is quite cool, but we are breaking the chill by building campfires.

Sunday, 2nd. In the morning read Oct. Atlantic. In the P. M. finished Fannie’s letter. Detail came for Lt. or trusty Srgt. to go out with 30 men as escort to brigade forage teams. Officers said they proposed sending me. I agreed if they wished it, to start at 7:30 A. M.

Corinth, Sunday, Nov. 2. I walked up to the Battery, the farthest I had walked since my lameness. Saw the boys off; they left their tents standing, their knapsacks etc. under charge of Lieutenant Simpson, and those unfit for the march. The inmates of the hospital were taken to the general hospital under Dr. Arnold, nine in number, viz: Orderly J. G. S. Hayward (fractured ankle), Corporal G. B. Jones (chronic diarrhea; waiting for discharge); W. W. Wyman (waiting for discharge); G. W. Benedict (diarrhea); E. W. Evans (fever); David Evans (convalescent); Alex. Ray (convalescent) ; E. R. Hungerford (chronic diarrhea); Jenk. L. Jones (bruised ankle), remained in the hospital until (November 9)

NOVEMBER 2D, SUNDAY.—I watch the daily orders of Adjutant and Inspector-Gen. Cooper. These, when “by command of the Secretary of War,” are intelligible to any one, but not many are by his command. When simply “by order,” they are promulgated by order of the President, without even consulting the Secretary; and they often annul the Secretary’s orders. They are edicts, and sometimes thought very arbitrary ones. One of these orders says liquor shall not be introduced into the city; and a poor fellow, the other day, was sentenced to the ball-and-chain for trying to bring hither his whisky from Petersburg. On the same day Gov. Brown, of Georgia, seized liquor in his State, in transitu over the railroad, belonging to the government!

Since the turning over of the passports to Generals Smith and Winder, I have resumed the position where all the letters to the department come through my hands. I read them, make brief statements of their contents, and send them to the Secretary. Thus all sent by the President to the department go through my hands, being epitomized in the same manner.

The new Assistant Secretary, Judge Campbell, has been ordering the Adjutant-General too peremptorily; and so Gen. Cooper has issued an order making Lieut.-Col. Peas an Acting Assistant Secretary of War, thus creating an office in defiance of Congress.

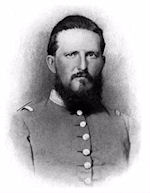

“We then hoped a few months would end the war and we would all be at home again. Sadly we were disappointed.”–Letters from Elisha Franklin Paxton.

Berryville, Clark Co., November 2, 1862.

I have just returned from a ride down to the camp of my old comrades, with whom I have spent a very pleasant day. The old tent in which I quartered last spring and winter looked very natural, but the appearance of the regiment was very much changed. But few of the officers who were with me are in it now. In my old company I found many familiar faces in those who went with me to Harper’s Ferry last spring a year ago. We then hoped a few months would end the war and we would all be at home again. Sadly we were disappointed. Many of our comrades have gone to their long home, and many more disabled for life. And now when we look to the future we seem, if anything, farther from the end of our troubles than when they began. Many of us are destined yet to share the fate of our dead and wounded comrades, a few perhaps survive the war, enjoy its glorious fruits, and spend what remains of life with those we love. We all hope to be thus blessed; but for my part I feel that my place must be filled and my duty done, if it cost me my life and bring sorrow to the dear wife and little ones who now watch my path with so much anxiety and pray so fervently for my safe deliverance. The sentiment which I try to hold and cherish is God’s will and my duty to be done, whatever the future may have in store for me. I am glad to feel, darling, that although I have been writing to you for nearly eighteen months, and this has been the substitute for our once fond intercourse, I feel when I write now that I miss you none the less than I did when this cruel war first placed the barrier of separation between us. I hope as fondly as ever that the day may soon come when we will live in peace and quiet together. Eight years ago to-day, Love, we began our married life, very happy and full of hope for the future. Thus far it has been made of sunshine and shadow, joy and sorrow, strangely intermingled. The darker shade of life has for a long time predominated; may we not hope for a change of fortune ere long?

“…Pettit opened fire with his two ten pounder Parrots, and to our astonishment, dropped his first shells immediately in front of them.” –Diary of Josiah Marshall Favill.

November 2d. Early in the morning the pickets reported clouds of dust advancing towards the Gap, which at once brought out our field glasses, to scan the magnificent valley lying at our feet. We saw the clouds of dust, and soon made out a column of infantry advancing, and from their formation, they evidently expected to find the Gap unoccupied. When they came within artillery range, Pettit opened fire with his two ten pounder Parrots, and to our astonishment, dropped his first shells immediately in front of them. I noted the flight of the shells from a position kneeling alongside one of the guns, and could easily trace its flight from beginning to end. He calculated the distance at about a mile, and we were not a little proud of Pettit’s wonderful skill in judging distances. The rebel column promptly disappeared under cover of some friendly woods. At five o’clock much to our disgust, we were relieved by the brigade of regulars from Sykes’s division. I remained on the top of the mountain to point out the position of the picket line, and while waiting for the fresh troops to come up, dismounted, and lay down on the sweet, short grass, green as emerald, and enjoyed a charming little reverie entirely alone, without a human being in sight.

We enjoyed life on the mountain top, and were loath to descend, but not being our own masters have to take what is set before us. Headquarters are established in a small house by the road side, just at the base of the mountain. There are two fine young women, who with the entire family sit down with us to eat, our mess furnishing the cooks, and the food, and the house the appointments. The ladies are rebellious, but fond of attention, and so we have a good deal of fun.

Sunday, November 2.—Went down to the depot this morning, as I heard General Withers’s division was passing through on their way west, and I was in hopes I would hear something of my brother; was not disappointed, as I met Colonel Buck and Captain Muldon of the Twenty-fourth Alabama Regiment. They told me he was well. His company has gone another route. The army is en route for Murfreesboro, the western portion of this state. It is thirty miles south-east of Nashville.

Went to the Episcopal Church this morning; heard a very good sermon. Mr. Denniston introduced me to some very nice ladies belonging to the place. He is post chaplain here. He called to see us yesterday.