Saturday, 2nd—Went to Granville. I rode Jimmy’s gray horse and left my mule with his boy. Staid all night with Capt. Trousdale; had to paddle over the river in a canoe and swim our horses.

Thursday, May 2, 2013

May 2d. Commences with clear and pleasant weather. Nothing occurred worthy of mention during nearly the entire day, the regular routine of naval discipline being gone through with on this day as upon all other days; at eight thirty o’clock, P. M., lights seen up Red River and reported from lookouts at mast-head; beat to quarters, and got ship ready for action. In a short time they made their appearance coming out of Red River, signalizing to us by different colored lights; as soon as they came within hailing distance, hailed them; they gave us to understand that they were respectively the U. S. gunboats Arizona and Estrella from Brashear City; they steamed on ahead of us, and anchored close in shore.

Near Port Gibson, Miss., Saturday, May 2. Awoke at 2 A. M. In the saddle at 3:30, and moved on. By sunrise we were on the ground of yesterday’s action. They met the enemy and drove them for five miles, disputing every inch. Captured many prisoners and took one battery. The dead were yet unburied in many instances, one lay on the roadside with the upper part of his head taken off by a cannon ball. Many were wounded, as they took the advantage of the unevenness of the country to attack us by surprise. Passed the 1st Wisconsin Battery, which had done good execution the day before. Finally we passed the brush hospitals along the road and marched unmolested to Port Gibson. Enemy left two bridges burned behind them.

Unhitched, watered and fed. Rested ourselves about two hours, when we again started, crossed the stream over which was a chain bridge, crossed on a rough pontoon of slabs which. nearly sank under water under the artillery. General Grant, careworn and nearly covered with dust, sat on the bank watching the progress of his advancing army. Marched through at double quick until very late, when the infantry laid down in the road, and we turned to the right in the field for three hours’ and a half sleep, out of which we had to feed, water, etc. Laid down without any supper and slept. Oh how sweet, but very short. Nine miles from Port Gibson.

Camp White, May 2, 1863.

Dearest L—: — Yours and the monthlies were handed me last night. No hurry about the “duds.” As for shoulder-straps, it would make no difference how it’s done if it’s according to custom or regulations. I don’t want to start a new fashion. Regulations require straps of a certain size, color, etc., a silver eagle, etc., etc. I would sooner have simply the eagle than a strap twice as big as the rule, but of no importance. Glad to get the monthlies.

We are fortifying, partly to occupy time, partly to be safe. Will [shall] be at it some time.

Uncle talks of coming up. If he does, you may bring one or more of the boys if you can do so conveniently, and if he asks you. . . .

Affectionately,

R.

Mrs. Hayes.

Saturday, 2d—The weather has been warm and quite pleasant for several days and the roads are drying fast. Things are very quiet here. Colonel Hall is now in command of our brigade. We have drill twice a day, though this afternoon there was none, in order to give the boys time to wash their clothes and clean up for inspection. I received $5.00 from Captain McLoney, for the month of April, as cook for the officers’ mess.

May 2 — Moved camp to-day to near Dayton, a pleasant little village situated in a beautiful and fertile country on the Harrisonburg and Warm Spring pike four miles southwest of Harrisonburg. We are now camped at a schoolhouse about half mile north of Dayton.

May 2, Saturday. Thick rumors concerning the Army of the Potomac, — little, however, from official sources. I abstain from going to the War Department more than is necessary or consulting operators at the telegraph, for there is a hazy uncertainty there. This indefiniteness, and the manner attending it, is a pretty certain indication that the information received is not particularly gratifying. Whether Hooker refuses to communicate, and prevents others from communicating, I know not. Other members of the Cabinet, like myself, are, I find, disinclined to visit the War Department under the circumstances.

A very singular declaration by John Laird, Member of Parliament and one of the builders of the pirate Alabama, has been shown. Laird said in Parliament, in reply to Thomas Baring, that the Navy Department had applied to him to build vessels. It is wholly untrue, a sheer fabrication. But John Laird writes to Howard of New York, that he (Howard) had said something to him (Laird) about building vessels for the Government. Howard, I judge, was Laird’s agent or broker to procure, if possible, contracts for him or his firm, but did [not] succeed. The truth is, our own shipbuilders, in consequence of the suspension of work in private yards early in the war, were clamorous for contracts, and the competition was such that we would have had terrible indignation upon us had we gone abroad for vessels, which I never thought of doing.

May 2, 3 & 4, 1863 – Union (Gen. Hooker) … Confederate (Gen. Lee) … Gen. Jackson mort. wd.

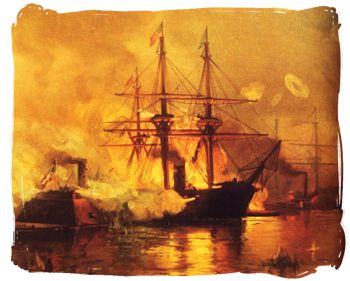

Lithograph – Copyrighted 1889 by Kurz & Allison, Art Publishers, Chicago, U.S.A.

Library of Congress image.

2d May (Saturday).—As the steamer had not arrived in the morning, I left by railroad for Galveston. General Scurry insisted upon sending his servant to wait upon me, in order that I might become acquainted with “an aristocratic negro.” “John” was a very smart fellow, and at first sight nearly as white as myself.

In the cars I was introduced to General Samuel Houston, the founder of Texan independence. He told me he was born in Virginia seventy years ago, that he was United States senator at thirty, and governor of Tennessee at thirty-six. He emigrated into Texas in 1832; headed the revolt of Texas, and defeated the Mexicans at San Jacinto in 1836. He then became President of the Republic of Texas, which he annexed to the United States in 1845. As Governor of the State in 1860, he had opposed the secession movement, and was deposed. Though evidently a remarkable and clever man, he is extremely egotistical and vain, and much disappointed at having to subside from his former grandeur. The town of Houston is named after him. In appearance he is a tall, handsome old man, much given to chewing tobacco, and blowing his nose with his fingers.[1]

I was also introduced to another “character,” Captain Chubb, who told me he was a Yankee by birth, and served as coxswain to the United States ship Java in 1827. He was afterwards imprisoned at Boston on suspicion of being engaged in the slave trade; but he escaped. At the beginning of this war he was captured by the Yankees, when he was in command of the Confederate States steamer Royal Yacht, and taken to New York in chains, where he was condemned to be hung as a pirate; but he was eventually exchanged. I was afterwards told that the slave-trading escapade of which he was accused consisted in his having hired a coloured crew at Boston, and then coolly selling them at Galveston.

At 1 P.M., we arrived at Virginia Point, a tete-de-pont at the extremity of the main land. Here Bates’s battalion was encamped—called also the “swamp angels,” on account of the marshy nature of their quarters, and of their predatory and irregular habits.

The railroad then traverses a shallow lagoon (called Galveston Bay) on a trestle-bridge two miles long; this leads to another tete-de-pont on Galveston island, and in a few minutes the city is reached.

In the train I had received the following message by telegraph from Colonel Debray, who commands at Galveston:—”Will Col. Fremantle sleep to-night at the house of a blockaded rebel?” I answered:—”Delighted;” and was received at the terminus by Captain Foster of the Staff, who conducted me in an ambulance to headquarters, which were at the house of the Roman Catholic bishop. I was received there by Colonel Debray and two very gentlemanlike French priests.

We sat down to dinner at 2 P.M., but were soon interrupted by an indignant drayman, who came to complain of a military outrage. It appeared that immediately after I had left the cars a semi-drunken Texan of Pyron’s regiment had desired this drayman to stop, and upon the latter declining to do so, the Texan fired five shots at him from his “six-shooter,” and the last shot killed the drayman’s horse. Captain Foster (who is a Louisianian, and very sarcastic about Texas) said that the regiment would probably hang the soldier for being such a disgraceful bad shot.

After dinner Colonel Debray took me into the observatory, which commands a good view of the city, bay, and gulf.

Galveston is situated near the eastern end of an island thirty miles long by three and a half wide. Its houses are well built; its streets are long, straight, and shaded with trees; but the city was now desolate, blockaded, and under military law. Most of the houses were empty, and bore many marks of the ill-directed fire of the Federal ships during the night of the 1st January last.

The whole of Galveston Bay is very shallow, except a narrow channel of about a hundred yards immediately in front of the now deserted wharves. The entrance to this channel is at the north-eastern extremity of the island, and is defended by the new works which are now in progress there. It is also blocked up with piles, torpedoes, and other obstacles.

The blockaders were plainly visible about four miles from land; they consisted of three gunboats and an ugly paddle steamer, also two supply vessels.

The wreck of the Confederate cotton steamer Neptune (destroyed in her attack on the Harriet Lane), was close off one of the wharves. That of the Westfield (blown up by the Yankee Commodore), was off Pelican Island.

In the night of the 1st January, General Magruder suddenly entered Galveston, placed his field-pieces along the line of wharves, and unexpectedly opened fire in the dark upon the Yankee war vessels at a range of about one hundred yards; but so heavy (though badly directed) was the reply from the ships, that the field-pieces had to be withdrawn. The attack by Colonel Cook upon a Massachusetts regiment fortified at the end of a wharf, also failed, and the Confederates thought themselves “badly whipped.” But after daylight the fortunate surrender of the Harriet Lane to the cotton boat Bayou City, and the extraordinary conduct of Commodore Renshaw, converted a Confederate disaster into the recapture of Galveston. General Magruder certainly deserves immense credit for his boldness in attacking a heavily armed naval squadron with a few field-pieces and two river steamers protected with cotton bales and manned with Texan cavalry soldiers.

I rode with Colonel Debray to examine Forts Scurry, Magruder, Bankhead, and Point. These works have been ingeniously designed by Colonel Sulokowski (formerly in the Austrian army), and they were being very well constructed by one hundred and fifty whites and six hundred blacks under that officer’s superintendence, the blacks being lent by the neighbouring planters.

Although the blockaders can easily approach to within three miles of the works, and although one shell will always “stampede” the negroes, yet they have not thrown any for a long time.[2]

Colonel Debray is a broad-shouldered Frenchman, and is a very good fellow. He told me that he emigrated to America in 1848; he raised a company in 1861, in which he was only a private; he was next appointed aide-de-camp to the Governor of Texas, with the rank of brigadier-general; he then descended to a major of infantry, afterwards rose to a lieutenant-colonel of cavalry, and is now colonel.

Captain Foster is properly on Magruder’s Staff, and is very good company. His property at New Orleans had been destroyed by the Yankees.

In the evening we went to a dance given by Colonel Manly, which was great fun. I danced an American cotillon with Mrs Manly; it was very violent exercise, and not the least like anything I had seen before. A gentleman stands by shouting out the different figures to be performed, and every one obeys his orders with much gravity and energy. Colonel Manly is a very gentlemanlike Carolinian; the ladies were pretty, and, considering the blockade, they were very well dressed.

Six deserters from Banks’s army arrived here to-day. Banks seems to be advancing steadily, and overcoming the opposition offered by the handful of Confederates in the Teche country.

Banks himself is much despised as a soldier, and is always called by the Confederates Mr Commissary Banks, on account of the efficient manner in which he performed the duties of that office for “Stonewall” Jackson in Virginia. The officer who is supposed really to command the advancing Federals, is Weitzel; and he is acknowledged by all here to be an able man, a good soldier, and well acquainted with the country in which he is manœuvring.

[1] He is reported to have died in August 1863.

[2] Such a stampede did occur when the blockaders threw two or three shells. All the negroes ran, showing every sign of great dismay, and two of them, in their terror, ran into the sea, and were unfortunately drowned. It is now, however, too late for the ships to try this experiment, as some heavy guns are in position. A description of the different works is of course omitted here.

2nd. Major Purington ordered on a scout with 150 men towards Traversville. 7th on the Albany road, I went along. Learned there were 900 rebels in the fight yesterday. Cheke among them. Went to a house and saw another wounded man, wounded in the charge near Monticello, hit in thigh. Rode four to eight miles, leg bleeding, Arthur Brannon of Lebanon, Ky., Shewarth’s Regt., wished the war had never commenced, still willing to fight. Citizens represented nearly 100 wounded. All demoralized. Officers could not get them to stand ground. Got into camp at 8 P. M. Rained during the night. I got wet enough.