Letter From Henry K. Douglas To Mrs. Paxton

May 4, 1863.

Madam: As the senior officer of Gen’l Paxton’s staff, and a person with whom he was probably more intimate than with any one in the brigade, I deem it my duty, although a painful one, to notify you of the circumstances of his death. He fell yesterday morning while bravely leading his brigade into action, and lived only about an hour after receiving his wound. As soon as he was struck he lifted his hand to his breast-pocket. In that pocket I knew he kept his Bible and the picture of his wife, and his thoughts were at that moment of heaven and his home. Beloved and esteemed by officers and men, his loss is deeply mourned, and the brigade mingle their tears with those of his family relations. I have for some time thought that the General expected the first battle in which he led his brigade would be his last, and I had observed, and am satisfied from various conversations with him, that he was preparing his mind and soul for the occasion. It is a consolation to know that while he nobly did his duty in the field and camp without regard to personal consequences, he had been convinced that there was a home beyond this earth where the good would receive an eternal reward. For that home he had richly prepared himself, and, I confidently hope, is there now. Almost the last time I saw him, and just before the brigade moved forward into the fight, he was sitting behind his line of troops, and, amidst the din of artillery and the noise of shell bursting around him, he was calmly reading his Bible and there preparing himself like a Christian soldier for the contest.

Dr. Cox, A. D. C, has already departed with his body for home.

__________

Letter From Henry K. Douglas To J. G. Paxton

Hagerstown, Md., Feb. 18,1893.

Yours of the 14th is received to-day. I knew your father very well. When he was on the staff of Gen’l Jackson, so was I; and for a time, when he commanded the Stonewall Brigade, I was the A. A. G. and A. I. G. of the brigade, in rank its senior staff officer. My relations with him were very close—indeed, confidential.

I had observed, during the winter of 1862-63, a growing seriousness on his part in every respect. There was nothing morbid about it, but he was much given to religious thought and conversation. He was a very regular reader of the Bible, and, I think, often talked with Gen’l Jackson on the same subject. He was thoroughly impressed with the conviction that he would die early in the opening campaign, and was determined to prepare for that fate.

In my letter to your mother, written the day after his death, I merely alluded to certain conversations which I will now explain more explicitly.

The night of the 2nd, Gen’l Paxton seemed—as we in fact all were—very much depressed at the wounding of Gen’l Jackson. Late that night, in the course of a conversation with me, your father quietly but with evident conviction expressed his belief that he would be killed the next day. He told me where in his office desk certain papers were tied up and labelled in regard to his business, and asked me to write to his wife immediately after his death. I was young and not given to seriousness then; but I was so impressed with his sadness and earnestness, and all the gloom of the surroundings, that I did not leave him until after midnight.

The next morning we were astir very early. I found Gen’l Paxton sitting near a fence, in rear of his line, with his back against a tree, reading the Bible. He received me cheerfully. I had been with him but a few minutes when the order came for his brigade to move. He put the Bible in his breast-pocket, and directing me to take the left of the brigade, he moved off to the right of it. I never saw him again. I find, in looking at my brief diary of that day, that he had been killed for some time before I knew it, and that I was commanding the brigade by issuing orders in his name long after his death. “When I knew of it, I informed Col. Funk, who immediately assumed command. I mentioned in the letter to your mother that he lived an hour after his wounding. Capt. Barton says this is an error, and it is probable he is correct. I was not with Gen’l Paxton when he was shot, and I suppose that what I stated in my letter was obtained from some one else. Capt. Barton was with the General. I find this in my notes: “I missed Gen’l Paxton and the rest of the staff; but as I missed part of the 2nd Regiment, I thought it and the General had become temporarily separated from the rest of the Brigade.” I find in my notes of the 4th: “I wrote a letter to Mrs. Paxton concerning the death of the General.” This is the letter a copy of which you sent me, and I am very glad to get it.

Gen’l Paxton was a unique character. He was a man of intense convictions and the courage of them. Kindhearted, he was often brusque to rudeness. He was conscientious in the discharge of his duties, and painstaking. He was of excellent judgment, slow and sure, and yet fond of dash in others. He was esteemed by the officers, beloved by the men, and respected by all. He was an excellent officer, a faithful, brave and conscientious soldier. He had a keen sense of humor, well restrained, and often laughed at and condoned recklessness of which he did not approve. I think I must have tried him often; but if so, he never let me know it. I had his friendship, and in all his friendships he was staunch and true.

P.S. I find this in the account of my interview with Gen’l Jackson on Sunday evening, the 3rd: “He spoke feelingly of Gen’l Paxton and Capt. Boswell, both dead, and his eyes filled with tears as he mentioned their names. He asked me to tell him all about the movements of the old brigade. When I described to him its evolutions: how Gen’l Paxton was reading his Bible when the order came to advance; how he was shortly afterwards mortally wounded; how Gen’l Stuart led the brigade in person, shouting, “Charge, and remember Jackson!” etc., etc., his eyes lighted up with the fire of battle as he exclaimed, “It was just like them—just like them!”

__________

Letter From Randolph Barton To J. G. Paxton

Baltimore, MA., Sept. 14, 1885.

My recollection is that in the summer or September of 1862, your father, who up to that time had been a member of the staff of Gen’l Jackson (Stonewall), was by that officer appointed to the command of the Stonewall Brigade,—Gen’l Winder, its last commander, having been killed at Cedar Mountain.

I was a brevet second lieutenant in Co. K, 2nd Va. Infantry, Stonewall Brigade, during the winter of 1862-863, and your father was at that time acting Brigadier Gen’l. Early in 1863, upon the recommendation of Mr. Henry K. Douglas, your father detailed me to act as Assistant Adjutant-Gen’1 of the brigade, and about March or April, 1863, I left my company and went to his headquarters. A little later the Confederate Congress confirmed his appointment as Brigadier-General, and thereupon, although he did not positively tell me that he wished me to remain with him permanently, he suggested that I should supply myself with a horse, which I took as a hopeful sign of my promotion.

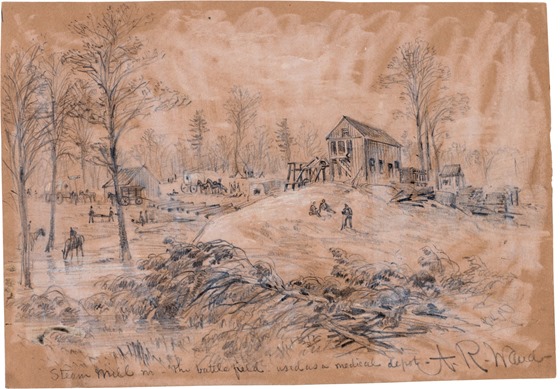

My impressions are not clear, at this length of time, as to your father’s religious life during the period immediately preceding the opening of the campaign of 1863, but I am sure he daily read his Bible, and on Sunday went to the brigade’s religious services, held in a large, rude log house, in which I remember distinctly to have seen Gen’l Jackson with great regularity.

On the afternoon of May 2, 1863, about three o’clock, Gen’l Jackson’s command completed the flank movement which placed him in Hooker’s rear. Your father’s brigade brought up the rear of the column, and as it emerged from the dense pine forest and blinding dust upon the plank road leading from Orange C. H. to Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg, Gen’l Jackson halted it, allowed the rest of the column to go on, and for some moments, seated on a fallen log back in the woods, engaged your father in earnest conversation.

Gen’l Jackson then rejoined his column, your father formed his brigade across the road, about evenly divided by the road, and with his staff advanced down the road some few hundred yards. After a while firing commenced on the left, and one of us was despatched by your father to bring up the brigade in line of battle, which was done, and by nightfall we had resumed our position at the right of Gen’l Jackson’s line. The enemy had been completely surprised by the advance on our left, had fled in great confusion, and our brigade had been very slightly engaged.

We spent the early hours of that night on the roadside, or in shifting positions. Finally, about one o’clock the next morning, we got into the line of battle not far from the enemy. Our rest was constantly broken by volleys of musketry, and we all knew that daybreak would usher in an awful conflict. I was close to your father all this time, as my duty required, and recall now with vivid distinctness the fact that he was dressed in a handsome gray suit, which had only a day or so before been received from Richmond, having on its collar the insignia of a Brigadier-Gen’l. Perhaps the wreath was not on the collar, only the stars,—one of your father’s characteristics being aversion to display. By the very first dawn of day, when with difficulty print could be read, your father opened a Bible,—a very thick, short volume, probably gilt-edged,—read for some time, and as the sound of approaching conflict increased, carefully replaced it in his left breast-pocket, over his heart. In a few moments a staff officer from Gen’l Stuart, who had succeeded Gen’l Jackson, hurried us to the right of the plank road, and we were immediately engaged in a terrific battle. Our brigade had faced the enemy and were slowly advancing, firing as they advanced. I was within a foot or two of your father, on his left, both of us on foot, and in the line of our men. Suddenly I heard the unmistakable blow of a ball, my first thought being that it had struck a tree near us, but in an instant your father reeled and fell. He at once raised himself, with his arms extended, and as I bent over him to lift him I understood him to say, “Tie up my arm”; and then, as I thought, he died. Some of our men carried him off, and after a while, being severely wounded myself, I went back, passing his body in an ambulance.

__________

The following extracts are taken from the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. XXV,—Chancellorsville:

____

No. 398, P. 1006. Report Op Brig.-gen. E. E. Colston, C. S. Army, Comdg. Trimble’s Division

This was a most critical moment. The troops in the breastworks, belonging mainly (I believe) to General Pender’s and General McGowan’s brigades, were almost without ammunition, and had become mixed with each other and with the fragments of other commands. They were huddled up close to the breastworks, six and eight deep.

In the meantime, the enemy’s line was steadily advancing on our front and right, almost without opposition until I ordered the troops in the breastworks to open fire upon them. At this moment Paxton’s brigade, having moved by the right flank across the road, and then by the left flank in line of battle, advanced toward the breastworks. Before reaching them, the gallant and lamented General Paxton fell. The command devolved upon Colonel (J. H. S.) Funk, Fifth Virginia Regiment. The brigade advanced steadily, and the Second Brigade moved up at the same time. They opened fire upon the enemy and drove them back in confusion. . . .

I cannot, however, close this report without mentioning more particularly, first, the names of some of the most prominent of the gallant dead. Paxton, Garnett and Walker died heroically at the head of their brigades.

_____

No 399, P. 1012. Report Of Col. J. H. S. Funk, 5th Va. Infantry, Comdg. Paxton’s Brigade

I have the honor of submitting the following report of Paxton’s brigade in the late operations around Chancellorsville:

The brigade, under the command of Brig.-Gen. E. Frank Paxton, composed of the Second, Fourth, Fifth, Twenty-seventh and Thirty-third Virginia Infantry Regiments, left Camp Moss Neck on the morning of April 28, marching to Hamilton’s crossing, where we bivouacked. . . .

On the morning of May 3 (Sunday) we were aroused at daylight by the firing of our skirmishers, who had thus early engaged the enemy. At sunrise the engagement had become general, and though not engaged, and occupying the second line, the brigade suffered some loss from the terrific shelling to which it was exposed.

At 7 A.M. we were ordered to move across the plank road by the right flank about three hundred yards, and then by the left flank until we reached a hastily constructed breastwork thrown up by the enemy. At this point we found a large number of men of whom fear had taken the most absolute possession. We endeavored to persuade them to go forward, but all we could say was of but little avail. As soon as the line was formed once more, having been somewhat deranged by the interminable mass of undergrowth in the woods through which we passed, we moved forward. Here General Paxton fell while gallantly leading his troops to victory and glory.

_____

No. 309, P. 1006. Report Of Gen. R. E. Lee, C. S. Army, Comdg. Army Of Northern Virginia. Sept. 21, 1863

Many valuable officers and men were killed or wounded in the faithful discharge of duty. Among the former, Brigadier-General Paxton fell while leading his brigade with conspicuous courage in the assault on the enemy’s works at Chancellorsville. . . .