May 7th. Commences with pleasant weather; at six forty-five A. M., sent the Albatross down the river in search of the Sachem; at 9 A. M., inspected crew at quarters; at two P. M., the Albatross came up the river and made fast inshore ahead of us; at two forty P. M., the Sachem came up the river and anchored.

Tuesday, May 7, 2013

Thursday, 7th.—Reported Federals just across the river, and that General Beauregard had arrived at Vicksburg.

Near Black River, Thursday, May 7. 1st Brigade and Battery M. relieved General Logan’s on the river. His Division marched to the right, moved across the road into the shade.

Camp White, May 7, 1863.

Dearest: — The boxes came safely. The flag will not be cut. The coat fits well. Straps exactly according to regulations or none. The eagles are pretty and simple and I shall keep them until straps can be got of the size and description prescribed, viz., “Light or sky-blue cloth, one and three-eighths inches wide by four inches long; bordered with an embroidery of gold one fourth of an inch wide; a silver embroidered spread eagle on the center of the strap.”I am content with the eagles as they are but if straps are got, let them be “according to red-tape.” The pants fit Avery to a charm and he keeps them. What is the price? I’ll not try again until I can be measured. I do not need pants just now.

We have a little smallpox in Charleston. Lieutenant Smith has it, or measles. Also raids of the enemy threatened. I wouldn’t come up just now; before the end of the month it may be all quiet again. Bottsford’s sister and other ladies are going away today.

We are building a fort on the hill above our camp — a good position. We are in suspense about Hooker. He moves rapidly and boldly. If he escapes defeat for the next ten days he is the coming man. — Pictures O. K., etc., etc. — Love to all.

Affectionately,

R. B. Hayes.

Mrs. Hayes.

May 7, [1863]. — Another movement of the army of the Potomac, this time under General Hooker, a man of energy and courage. Whether able and skilful enough to handle so great an army is the question. He is confident and bold. His crossing the Rappahannock was sudden and apparently successful. It looked a little like separating his army. The great fighting [at Chancellorsville] was on Saturday and Sunday, reported vaguely as “indecisive.” Again this suspense — “with us or with our foes?” All day Sunday I was thinking and talking of the battle. The previous news satisfied me that about that time fighting would be done.

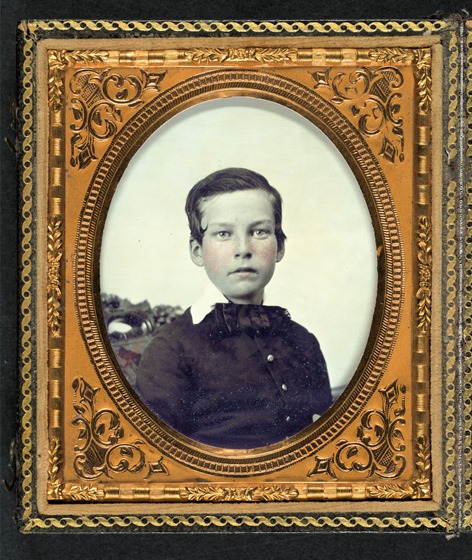

Private Charles H. Bickford of B Company, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment as a child.

Name from inscription on handwritten note in case; additional information on note includes date of birth, March 1844, date and place of death, May 3, 1863, at Chancellorsville, Virginia, and name of sister, Georgeanna Hunt.

Gift; Tom Liljenquist; 2010

Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs; Ambrotype/Tintype photograph filing series; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Record page for image is here.

Civil War Portrait 027

Thursday, 7th—One hundred and fifty prisoners captured at Grand Gulf were taken past here this morning; they all looked quite downhearted. A large train of provisions passed here for the army below. The roads are drying fast, which is making the hauling and marching better. The boys are all anxious to leave this place and move to the front. This is a low, unhealthy locality. An old negro here has picked up more than a thousand overcoats and blankets and is storing them away in his hut. These are thrown aside by the men marching out from the landing. On becoming warm and getting tired of their loads, they begin to unload about the first day’s march.

May 7 — To-day some Yankee cavalry advanced up the Valley as far as New Market, eighteen miles below Harrisonburg. When the report of their advance reached our camp we were ordered to move immediately with the battery to the Valley pike and select a good stand for the butcher business. We marched in quick time down the Warm Spring pike to Harrisonburg, and then went two miles below town on the Valley pike and put our guns into battery on a hill that afforded a first-class position which commanded the pike for a mile and a half on our front. All our available force in the Valley was in line and ready for the fray. My gun was in position on the extreme right of the line, in the edge of a wood and in perfect range and line with the pike for a mile in our front. Our force all told is very small at present, as General Jones’ brigade of cavalry is still raiding around somewhere in the mountains of West Virginia.

We remained in battery until after dark, then fell back a short distance and bivouacked for the night. The Yankees did not advance any further than little above New Market. As we were going to the front to-day great excitement and stir-up prevailed among the citizens in Harrisonburg and the country around. Refugees of all descriptions, sheep, cattle, and dogs, were streaming hastily up the Valley pike and out the Warm Spring road, conglomerated in one grand mixture of men, cattle, horses, negroes, sheep, hogs, and dogs, all fleeing from the invading foe and trying to escape the bluecoated scourge that was coming. One old citizen from down the Valley somewhere undoubtedly saw the Yankees this morning before he started, for when he passed us as we were going to the front he did not stop to tell us the news, but shouted, as he hastened and pressed toward the West Augusta Mountains: “Hurry up! you ought to been down there long ago.”

In Harrisonburg the excitement was set in the top notch. I saw men loading wagons with all kinds of furniture and household goods for removal to a more congenial clime, where war’s dread alarms are not so frequent. I saw one man running through the street with a clock under his arm. I suppose he was determined to run with time. I saw another man hastily leaving town with a fine mirror, striking out toward the heart of Dixie. War is surely a stirring-up affair, especially when it breaks out in a fresh place among peace-loving citizens.

7th May (Thursday).—We started again at 1.30 A.M. in a smaller coach, but luckily with reduced numbers, viz.—the Louisianian Judge (who is also a legislator), a Mississippi planter, the boatswain, the Government agent, and a Captain Williams, of the Texas Rangers.

Before the day broke we reached a bridge over a stream called Mud Creek, which was in such a dilapidated condition that all hands had to get out and cover over the biggest holes with planks.

The Government agent informed us that he still held a commission as adjutant-general to ——. The latter, it appears, is a cross between a guerilla and a horse thief, and, even by his adjutant-general’s account, he seems to be an equal adept at both professions. The accounts of his forays in Arkansas were highly amusing, but rather strongly seasoned for a legitimate soldier.

The Judge was a very gentlemanlike nice old man. Both he and the adjutant-general were much knocked up by the journey; but I revived the former with the last of the Immortalité rum. The latter was in very weak health, and doesn’t expect to live long; but he ardently hoped to destroy a few more “bluebellies “[1] before he “goes under.”

The Mississippi planter had abandoned his estate near Vicksburg, and withdrawn with the remnant of his slaves into Texas. The Judge also had lost all his property in New Orleans. In fact, every other man one meets has been more or less ruined since the war, but all speak of their losses with the greatest equanimity.

Captain Williams was a tall, cadaverous backwoodsman, who had lost his health in the war. He spoke of the Federal general, Rosecrans, with great respect, and he passed the following high encomium upon the North-Western troops, under Rosecrans’s command—

“They’re reglar great big h—llsnorters, the same breed as ourselves. They don’t want no running after, —they don’t. They ain’t no Dutch cavalry[2]—you bet!”

To my surprise all the party were willing to agree that a few years ago most educated men in the south regarded slavery as a misfortune and not justifiable, though necessary under the circumstances. But the meddling, coercive conduct of the detested and despised abolitionists had caused the bonds to be drawn much tighter.

My fellow-travellers of all classes are much given to talk to me about their “peculiar institution,” and they are most anxious that I should see as much of it as possible, in order that I may be convinced that it is not so bad as has been represented, and that they are not all “Legrees,” although they do not attempt to deny that there are many instances of cruelty. But they say a man who is known to ill-treat his negroes is hated by all the rest of the community. They declare that Yankees make the worst masters when they settle in the South; and all seem to be perfectly aware that slavery, which they did not invent, but which they inherited from us (English), is and always will be the great bar to the sympathy of the civilised world. I have heard these words used over and over again.

All the villages through which we passed were deserted except by women and very old men; their aspect was most melancholy. The country is sandy and the land not fertile, but the timber is fine.

We met several planters on the road, who with their families and negroes were taking refuge in Texas, after having abandoned their plantations in Louisiana on the approach of Banks. One of them had as many as sixty slaves with him of all ages and sizes.

At 7 P.M. we received an unwelcome addition to our party, in the shape of three huge, long-legged, unwashed, odoriferous Texan soldiers, and we passed a wretched night in consequence. The Texans are certainly not prone to take offence where they see none is intended; for when this irruption took place, I couldn’t help remarking to the Judge with regard to the most obnoxious man who was occupying the centre seat to our mutual discomfort,—”I say, Judge, this gentleman has got the longest legs I ever saw.” “Has he?” replied the Judge; “and he has got the d—dest, longest, hardest back I ever felt.” The Texan was highly amused by these remarks upon his personal appearance, and apologised for his peculiarities.

Crossed the Sabine river at 11.30 P.M.

[1] The Union soldiers are called ”bluebellies” on account of their blue uniforms. These often call the Confederates “greybacks.”

[2] German dragoons, much despised by the Texans on account of their style of riding.

May 7, Thursday. Our people, though shocked and very much disappointed, are in better tone and temper than I feared they would be. The press had wrought the public mind to high expectation by predicting certain success, which all wished to believe. I have not been confident, though I had hopes. Hooker has not been tried in so high and responsible a position. He is gallant and efficient as commander of a division, but I am apprehensive not equal to that of General-in-Chief. I have not, however, sufficient data for a correct and intelligent opinion. A portion of his plan seems to have been well devised, and his crossing the river well executed. It is not clear that his position at Chancellorsville was well selected, and he seems not to have been prepared for Stonewall Jackson’s favorite plan of attack. Our men fought well, though it seems not one half of them were engaged. I do not learn why Stoneman was left, or why Hooker recrossed the river without hearing from him, or why he recrossed at all.

It is not explained why Sedgwick and his command were left single-handed to fight against greatly superior numbers — the whole army of Lee in fact — on Monday, when Hooker with all his forces was unemployed only three miles distant. There are, indeed, many matters which require explanation.