MAY 8TH—We were ready to continue our march, but were not ordered out. Some white citizens came into camp to see the “Yankees,” as they call us. Of course they do not know the meaning of the term, but apply it to all Union soldiers. They will think there are plenty of Yankees on this road if they watch it. The country here looks desolate. The owners of the plantations are “dun gone,” and the fortunes of war have cleared away the fences. One of the boys foraged to-day and brought into camp, in his blanket, a variety of vegetables—and nothing is so palatable to us now as a vegetable meal, for we have been living a little too long on nothing but bacon. Pickles taste first-rate. I always write home for pickles, and I’ve a lady friend who makes and sends me, when she can, the best kind of “ketchup.” There is nothing else I eat that makes me catch up so quick. There is another article we learn to appreciate in camp, and that is newspapers—something fresh to read. The boys frequently bring in reading matter with their forage. Almost anything in print is better than nothing. A novel was brought in to-day, and as soon as it was caught sight of a score or more had engaged in turn the reading of it. It will soon be read to pieces, though handled as carefully as possible, under the circumstances. We can not get reading supplies from home down here. I know papers have been sent to me, but I never got them. The health of our boys is good, and they are brimful of spirits (not “commissary”). We are generally better on the march than in camp, where we are too apt to get lazy, and grumble; but when moving we digest almost anything. When soldiers get bilious, they can not be satisfied until they are set in motion.

Wednesday, May 8, 2013

Friday, 8th—I went to John Mitchell’s to meet A.; was not there. I went on to John West; saw Miss Jane Wiley; came back to D’s; found A. there. I came back to John West, and on to Dots Belt’s;. staid all night; on to Green Crews this morning.

May 8. — I went over to the headquarters of Whipple’s division this morning, and saw Dalton. He told me that General Whipple had died from the effects of his wound. Gave me my shoulder-straps. Went to Griffin’s headquarters and saw Batchelder, who told me that he could get me a place on General Crawford’s staff as aide. Was waked up early in the morning (4 A.M.) to send Captain Lubey and his canvas train up to Kelly’s Ford to meet and cross over General Stoneman and his cavalry. The animals for the train arrived at 9 minutes of 8, and the train started at 8.15 A.M. Went to General Stoneman’s headquarters in the evening. Heard here when I came back that was to be relieved. Day cloudy.

May 8—We left here at 8 A.M., to return to Kinston, and got there at 3 P.M.—ten miles—awful road. Waded through mud, water and sand the whole way. My feet are cut up pretty badly.

Fannie Virginia Casseopia Lawrence, a redeemed slave child, five years of age as she appeared when found in slavery. Redeemed in Virginia by Catharine [i.e., Catherine] S. Lawrence; baptized in Brooklyn, at Plymouth Church by Henry Ward Beecher, May 1863 / photographed by Kellogg Brothers, 279 Main Street, Hartford Conn.

Fannie was one of the most photographed of “slave children” used as propaganda by abolitionists during the civil war. Despite her light color, she was considered black because of mixed black.white ancestry. Fannie was considered an “octoroon”as someone who was of 1/8 black ancestry.

Henry Ward Beecher, of course, was one of the leading abolitionist spokesmen in the U. S., a preacher and brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Civil War Portrait 028

Stoneman Station, Va.,

Friday, May 8, 1863.

Dear Sister L.:—

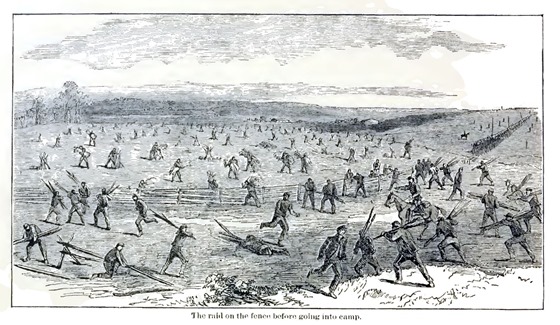

Well, now to dash right into it, for I have something to write this time. We left camp Monday, April 27th, with eight days’ rations, and night found us at Hartwood Church, ten miles up the river. Here our corps (Fifth) joined the Eleventh and Twelfth corps, and next day we all marched to Kelly’s Ford. Wednesday morning early we crossed the river, and after marching hard all day forded the Rapidan, water waist deep, and the Eighty-third was sent to the front on picket. Next day we marched on again, and noon found us at Chancellorsville, a big brick house in a field surrounded by a wilderness of woods. Here we halted and spent the night, and here the great battle of the war was fought.

Friday morning our brigade made a reconnoissance towards the Rappahannock. On the road we found a newly deserted camp with tents all standing, and in it some of the French knapsacks and muskets we lost at Gaines’ Mill. We returned in the afternoon and there was some skirmishing with the enemy. Saturday was spent in building breastworks, and in the afternoon the rebels arrived. They attacked our lines furiously in the center, but were repulsed. At first the Eleventh Corps (Sigel’s Dutchmen) gave way, and Sickles’ division (the one Alf is in) was sent in. They drove the rebs back and held them. At night we lay on our arms behind our works. The moon was full and it was almost as light as day. Six or seven times the attack was made in the same place and every time repulsed. It was an anxious night, for the morrow all felt sure would be a bloody Sunday, and so it was. We were up at light and moved off to the right of the center, and immediately went to work building breastworks. Just as the sun came up the enemy came on. Their whole army was massed on half a mile of our center, and Jackson told his men “they must break our line if it killed every man they had,” but we were prepared for them. Our first line in front of the works was overpowered and driven in, and they rushed on. Artillery and infantry met them. Protected by their breastworks, our men poured it into them. Grape and canister swept through their columns, mowing them down. Still, on they came, like a vast herd of buffaloes, struggling over the trees and brush, dashing, brave, impetuous, but doomed to destruction. Thousands of them charged right up to our works, but, the line shattered, comrades killed, they could do nothing but throw down their arms, retreat being impossible. For six hours they persevered and then withdrew. You must imagine the scene—I cannot describe it. The roar was unearthly; there is no better word for it. I shudder at the slaughter. Ours was fearful enough, but a drop in the bucket to theirs. In it all our brigade did not fire a shot. Right in sight of the fighting, expecting to be attacked, they spent the day and night, and next day and night. Monday and Tuesday we were waiting for them, confident of victory. While we were busy there, Sedgwick with his corps crossed the river and took the heights of Fredericksburg, capturing their big guns, but I learn that he was afterwards driven back.[1]

Wednesday, to our great surprise, we recrossed the river and returned to our old camps. No one seems to understand the move, but I have no doubt it is all right. It rained all day and it was the toughest march we’ve had in many a day. Tramp, tramp, through the mud. I was almost ready to drop when I got in, but I did not fall out, though half the regiment did when they found we were coming to camp.

So here we are with eight days’ rations and orders to be ready to march again. I don’t know anything about the meaning of it. I would give half a dollar for to-day’s Herald.

[1] Note.—Error—Sedgwick was not driven back, but recrossed the river at Banks’ Ford.

by John Beauchamp Jones

MAY 8TH.—To-day the city is in fine spirits. Hooker had merely thrown up defenses to protect his flight across the river. The following dispatch was received last night from Gen. Lee:

“CHANCELLORVILLE, May 7th, 1863.

“TO HIS EXCELLENCY, PRESIDENT DAVIS.

“After driving Gen. Sedgwick across the Rappahannock, on the night of the 4th inst., I returned on the 5th to Chancellorville. The march was delayed by a storm, which continued all night and the following day. In placing the troops in position on the morning of the 6th, to attack Gen. Hooker, it was ascertained he had abandoned his fortified position. The line of skirmishers was pressed forward until they came within range of the enemy’s batteries, planted north of the Rappahannock, which, from the configuration of the ground, completely commanded this side. His army, therefore, escaped with the loss of a few additional prisoners.

“(Signed) R. E. LEE, General.”

Thus ends the career of Gen. Hooker, who, a week ago, was at the head of an army of 150,000 men, perfect in drill, discipline, and all the muniments of war. He came a confident invader against Gen. Lee at the head of 65,000 “butternuts,” as our honest poor-clad defenders were called, and we see the result! An active campaign of less than a week, and Hooker is hurled back in disgrace and irreparable disaster! Tens of thousands of his men will never live to “fight another day”—and although the survivors did “run away,” it is doubtful whether they can be put in fighting trim again for many a month. [click to continue…]

May 8.—President Lincoln issued a proclamation preliminary to the enforcement of the “act for enrolling and calling out the National forces, and for other purposes,” defining the position and obligations of inchoate citizens under that law.— (Doc. 189.)

—The Nevada Union of this date assured its readers that there were active Southern guerrillas at work in Tulare County, California! and Los Angeles was, in every thing but form, a colony of the confederate States, where an avowal of loyalty was attended with personal danger. “We are no alarmist; but in view of the condition of affairs, and the large immigration thither, composed largely of secession sympathizers, we again warn Union men that they cannot be too wide awake nor too hasty in organization. We have now before us a late copy of The Red Bluff Independent, in which is given an account of the frustrated attempt on the part of secessionists to capture Fort Crook in the northern part of California. The parties to whom was intrusted the carrying out of the rebel enterprise, approached a citizen of that section, offering ample inducements for him to engage in the attempt, stating to him the plans and intentions of the secessionists, which were to capture the fort with its arms and ammunition—which, by the way, could have been easily accomplished at that time by a dozen men—and use it as a rendezvous for guerrillas. They struck the wrong man, and the consequence was, that information of their movements was conveyed to the fort, and the parties were arrested, and are now in irons at the fort, awaiting the order of General Wright.”

—Secretary E. M. Stanton sent the following despatch to the Governor of Pennsylvania: “The President and the General-in-Chief have just returned from the army of the Potomac. The principal operations of General Hooker failed, but there has been no serious disaster to the organization and efficiency of the army. It is now occupying its former position on the Rappahannock, having recrossed the river without any loss in the movement. Not more than one third of General Hooker’s force was engaged. General Stoneman’s operations have been a brilliant success. Part of his force advanced to within two miles of Richmond, and the enemy’s communications have been cut in every direction. The army of the Potomac will speedily resume offensive operations.”

—The ship Crazy Jane, was captured in Tampa Bay, Fla., by the gunboat Tahoma.—Earl Van Dorn, the rebel General, was shot and instantly killed this day by Dr. Peters, of Maury County, Tenn.

—To-night, a fleet of National gunboats and mortar-schooners, commenced the attack on the rebel batteries at Port Hudson, Miss.