May 11th. Is ushered upon us with pleasant weather, and light breezes from south-east. From noon to 1 o’clock, A. M., heavy firing heard down the river; at five fifty U. S. steamer Estrella came down Red river from Alexandria, with despatches to Commodore Palmer; at six forty-five the Albatross got under way and stood up the river; sent our pilot, Mr. Carroll, on board of her; at nine o’clock inspected crew at quarters, employed placing logs on port side of ship to protect the boilers and machinery against assaults from the enemy’s rams or iron-clad boats; Albatross came down the river and anchored in her old berth; at noon, a tug came down from upper fleet, Porter’s, with despatches and a mail; at one P. M., the gunboat Estrella got under way and entered the mouth of Red river on her return to Alexandria; at one thirty the tug-boat followed her, steaming away very fast; at three o’clock the steam tug and tender to the ship Benton came down and out of Red river, having Rear-Admiral Porter on board, and came alongside of us; Admiral Porter came on board of us and communicated with the Commodore. These are all the important occurrences of this day, also all the arrivals and departures of vessels at this station.

Saturday, May 11, 2013

Near Raymond, Monday, May 11. Harnessed and fed at 3 o’clock, it being a standing order from Grant that all troops be under arms at that hour and remain so for one hour. At sunrise we started out in the road and laid by our horses until noon, waiting to move on. Logan’s Division passed by. At last moved on about a mile and went to park. Came to action front [position known as “action” in tactics—ready for open fire if necessary], stretched tarpaulins. Forage wagons sent out when there came an orderly at full speed with orders to march immediately. All hands were busy in a moment, but before half the horses were harnessed there came another, and the order was countermanded and all was quiet again. I was on guard. Went on at 1 o’clock in the night, to listen to the bugles and watch the rising fires of the drowsy army just aroused from dreams of better and happier times to come.

11th May (Monday). — General Hebert is a good-looking creole.[1] He was a West-Pointer, and served in the old army, but afterwards became a wealthy sugar-planter. He used to hold Magruder’s position as commander-in-chief in Texas, but he has now been shelved at Munroe, where he expects to be taken prisoner any day; and, from the present gloomy aspect of affairs about here, it seems extremely probable that he will not be disappointed in his expectations. He is extremely down upon England for not recognising the South.[2]

He gave me a passage down the river in a steamer, which was to try to take provisions to Harrisonburg; but, at the same time, he informed me that she might very probably be captured by a Yankee gunboat.

At 1 P.M. I embarked for Harrisonburg, which is distant from Munroe by water 150 miles, and by land 75 miles. It is fortified, and offers what was considered a weak obstruction to the passage of the gunboats up the river to Munroe.

The steamer was one of the curious American river boats, which rise to a tremendous height out of the water, like great wooden castles. She was steered from a box at the very top of all, and this particular one was propelled by one wheel at her stern.

The river is quite beautiful; it is from 200 to 300 yards broad, very deep and tortuous, and the large trees grow right down to the very edge of the water.

Our captain at starting expressed in very plain terms his extreme disgust at the expedition, and said he fully expected to run against a gunboat at any turn of the river.

Soon after leaving Munroe, we passed a large plantation. The negro quarters were larger than a great many Texan towns, and they held three hundred hands.

After we had proceeded about half an hour, we were stopped by a mounted orderly (called a courier), who from the bank roared out the pleasing information, “They’re a-fighting at Harrisonburg.”, The captain on hearing this turned quite green in the face, and remarked that he’d be “dogged” if he liked running into the jaws of a lion, and he proposed to turn back; but he was jeered at by my fellow-travellers, who were all either officers or soldiers, wishing to cross the Mississippi to rejoin their regiments in the different Confederate armies.

One pleasant fellow, more warlike than the rest, suggested that as we had some Enfields on board, we should make “a little bit of a fight,” or at least “make one butt at a gunboat.” I was relieved to find that these insane proposals were not received with any enthusiasm by the majority.

The plantations, as we went further down the river, looked very prosperous; but signs of preparations for immediate skedaddling were visible in most of them, and I fear they are all destined to be soon desolate and destroyed.

We came to a courier picket every sixteen miles. At one of them we got the information, “Gun-boats drove back,” at which there was great rejoicing, and the captain, recovering his spirits, became quite jocose, and volunteered to give me letters of introduction to a “particular friend of his about here, called Mr Farragut;” but the next news, “Still a-fightin’,” caused us to tie ourselves to a tree at 8 P.M., off a little village called Columbia, which is half-way between Munroe and Harrisonburg.

We then lit a large fire, round which all the passengers squatted on their heels in Texan fashion, each man whittling a piece of wood, and discussing the merits of the different Yankee prisons at New Orleans or Chicago. One of them, seeing me, called out, “I reckon, Kernel, if the Yankees catch you with us, they’ll say you’re in d—d bad company;” which sally caused universal hilarity.

[1] The descendants of the French colonists in Louisiana are called Creoles; most of them talk French, and I have often met Louisianian regiments talking that language.

[2] General Hehert is the only man of education I met in the whole of my travels who spoke disagreeably about England in this respect. Most people say they think we are quite right to keep out of it as long as we can; but others think our Government is foolish to miss such a splendid chance of “smashing the Yankees,” with whom we must have a row sooner or later.

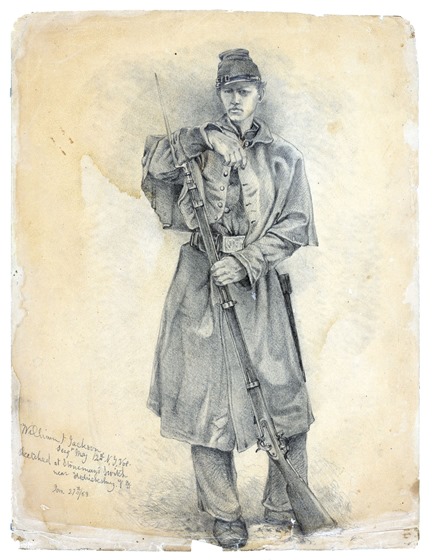

Study of infantry soldier on guard–William J. Jackson, Sergt. Maj. 12th N.Y. Vols.–Sketched at Stoneman’s Switch, near Fredricksburg, Va. Jan. 27th, 1863.

Drawn by Edwin Forbes.

Library of Congress image.

___________

Note: This image has been digitally adjusted for fade correction, color, contrast, and saturation enhancement and selected spot removal.

Note: This image has been digitally adjusted for fade correction, color, contrast, and saturation enhancement and selected spot removal.

Mrs. Lyon’s Diary.

May 11.—Went up in town to trade and see the sights. Took dinner on the boat. After dinner had a carriage and drove all over the city. Went to the capitol and all over it. Saw President Polk’s residence and visited his grave. It is in his own garden, or dooryard, in front of the house. Saw the residences of Colonel McNara and Colonel Heiman. Mr. Hill’s garden has a fountain and gold fish. Saw the Confederate General Zollicoffer’s residence and John Bell’s. Went to the State Prison (a little out of town). Went back to the boat and could not get supper and had to go back to the city to a restaurant.

Monday, 11th—We started this morning at 5 o’clock and marched about eight miles, when we stacked our arms until 3 p. m. We continued our march to Perkins’s Landing about forty-five miles below Vicksburg as the river runs, or twenty miles as the crow flies. Here we bivouacked for the night. The country here is very low and often overflows. The large plantations, such as Perkins’s, Holmes’s and Jeff Davis’s, are usually planted to cotton. The work is all done by slaves driven by overseers who live on the plantations, while the owners, planters, reside in more healthy localities.

MAY 11TH.—We drew two days’ rations and marched till noon. My company, E, being detailed for rear guard, a very undesirable position. General Logan thinks we shall have a fight soon. I am not particularly anxious for one, but if it comes I will make my musket talk. As we contemplate a battle, those who have been spoiling for a fight cease to be heard. It does not even take the smell of powder to quiet their nerves—a rumor being quite sufficient.

We have no means of knowing the number of troops in Vicksburg, but if they were well generaled and thrown against us at some particular point, the matter might be decided without going any further. If they can not whip us on our journey around their city, why do they not stay at home and strengthen their boasted position, and not lose so many men in battle to discourage the remainder? We are steadily advancing, and propose to keep on until we get them where they can’t retreat. My fear is that they may cut our supply train, and then we should be in a bad fix. Should that happen and they get us real hungry, I am afraid short work would be made of taking Vicksburg.

Having seen the four great Generals of this department, shall always feel honored that I was a member of Force’s 20th Ohio, Logan‘s Division, McPherson’s Corps of Grant’s Army. The expression upon the face of Grant was stern and care-worn, but determined. McPherson’s was the most pleasant and courteous—a perfect gentleman and an officer that the 17th corps fairly worships. Sherman has a quicker and more dashing movement than some others, a long neck, rather sharp features, and altogether just such a man as might lead an army through the enemy’s country. Logan is brave and does not seem to know what defeat means. We feel that he will bring us out of every fight victorious. I want no better or braver officers to fight under. I have often thought of the sacrifice that a General might make of his men in order to enhance his own eclat, for they do not always seem to display the good judgment they should. But I have no fear of a needless sacrifice of life through any mismanagement of this army.

May 11.—I note this as being one of the gloomiest days since the war. News has just been received that one of our brightest stars has left us; he has gone to shine in a more glorious sphere than this. The good and great General Stonewall Jackson has fallen; he was wounded at the battle of Chancellorsville, and lived a few days afterward. When I first heard of it I was speechless, and thought, with the apostle, “how unsearchable are His judgments, and His ways are past finding out. For who hath known the mind of the Lord.” Dark and mysterious indeed, are his ways. Who dare attempt to fathom them, when such men as Jackson are cut down in the zenith of their glory, and at the very hour of their country’s need?

The honor of taking this great man’s life was not reserved for the foe, but for his own men, as if it were a sacrifice they offered to the Lord, as Jephtha gave up his daughter.

“Is there one who hath thus, through his orbit of life,

But at distance, observed him through glory, through blame,

In the calm of retreat, in the grandeur of strife,

Whether shining or clouded, still high and the same.

O no, not a heart that e’er knew him but mourns

Deep, deep o’er the grave, where such glory is ‘shrined,

O’er a monument Fame will preserve, ‘mong the urns

Of the wisest, the bravest, the best of mankind!”

May 11, Monday. The President sent a note to my house early this morning, requesting me to call at the Executive Mansion on my way to the Department. When there he took from a drawer two dispatches written by the Secretary of State to Lord Lyons, in relation to prize captures. As they had reference to naval matters, he wished my views in regard to them and the subject-matter generally. I told him these dispatches were not particularly objectionable, but that Mr. Seward in these matters seemed not to have a correct apprehension of the duties and rights of the Executive and other Departments of the Government. There were, however, in this correspondence allusions to violations of international law and of instructions which were within his province, and which it might be well to correct; but as a general thing it would be better that the Secretary of State and the Executive should not, unless necessary, interfere in these matters, but leave them where they properly and legally belonged, with the judiciary. [I said] that Lord Lyons would present these demands or claims as long as the Executive would give them consideration, — acquiesced, responded, and assumed to grant relief, — but that it was wholly improper, and would, besides being irregular, cause him and also the State and Navy Departments great labor which does not belong to either. The President said he could see I was right, but that in this instance, perhaps, it would be best, if I did not seriously object, that these dispatches should go on; but he wished me to see them.

When I got to the Department, I found a letter from Mr. Seward, inclosing one from Lord Lyons stating that complaint had been made to his Government that passengers on the Peterhoff had been imprisoned and detained, and were entitled to damages. As the opportunity was a good one, I improved it to communicate to him in writing, what I have repeatedly done in conversation, that in the present state of the proceedings there should be no interference on his part, that these are matters for adjudication by the courts rather than for diplomacy or Executive action, and until the judicial power is exhausted, it is not advisable for the Departments to interfere, etc. The letter was not finished in season to be copied to-day, but I will get it to him to-morrow, I hope in season for him to read before getting off his dispatches.

11th. Issued five days’ rations in the morning. Watched the boys play chess. Had a good visit with Thede and Charley. News in papers a little more encouraging. In the evening heard Co. H boys sing. Enjoyed it much. Capt. Nettleton and Col. Ratliffe told me some news.