May 12th. This morning, at 1 o’clock, heard heavy firing down the river in the neighborhood of Port Hudson, which ceased in twenty minutes afterwards; at five forty -five steamer L. A. Sykes arrived from Alexandria, and at six thirty steamed back up Red river again; finished tricing the logs upon port side of ship; at 3 P. M., the steamer General Price came down Red river; light, easterly breezes; at four twenty the ironclad gunboat Pittsburgh, from Black river, came down and anchored ahead of us; ten of our men, volunteers who went on the expedition up Red river on board of her, returned to this ship with bag and hammock; at seven thirty-five the iron-clad Benton, flag-ship of Rear-Admiral Porter’s fleet, came down and out of Red river also; sent steam tug Ivy for our men, some twenty in number, detached on board of her for above referred-to expedition; the lads returned in good spirits, having had a pleasant trip to Alexandria and back, which place is now occupied by General Banks’s forces, and has the glorious stars and stripes once more flung to the breeze, whose colors the inhabitants are thrice glad to see once more. The boats did not come across the enemy during their absence. Many of the beautiful plantations of noted secessionists on Red river, left in charge of overseers, furnished the boys plenty of good food, such as chickens, turkeys, eggs, &c., and greatly did they enjoy this change of fodder from hard bread and salt horse.

Sunday, May 12, 2013

Tuesday, 12th.—Moved back to Hall’s Ferry Road. Reported Stonewall Jackson died from wounds received in the recent fight in Virginia.

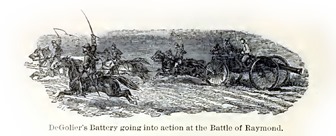

Raymond, Tuesday, May 12. Awoke at the usual hour, hitched up at daylight and took up the line of march. Travelled slowly, stopping frequently until about 12 M. When we neared the firing, the report of which we could hear all day, we were ordered forward at double quick for two miles, and formed in line of battle immediately under the brow of the hill. But the work was done by Logan’s Division. The firing gradually ceased and at 4 P. M. all was calm and still after the leaden storm, and the heroes were allowed to recite the startling events of the morning. They commenced driving the enemy at sunrise and about 10 A. M. they met them in superior force. The 1st Brigade suffered the worst. The 20th Ill. and 31st Iowa losing more men than in the five previous engagements, Shiloh and Corinth included. Many were severely wounded. Took about 50 or sixty prisoners.

6 P. M. we limbered to the front and marched into Raymond at double quick. It was dark before we got in, and the dust was so thick that I could not see the lead-rider. The howitzers were posted on the entrance of the Jackson road in the public square, and stood picket. The horses which had been all day without water or feed, obliged to stand in the harness hitched up. Drivers lying by their teams.

Tuesday Evening, May 12th.—How can I record the sorrow which has befallen our country! General T. J. Jackson is no more. The good, the great, the glorious Stonewall Jackson is numbered with the dead! Humanly speaking, we cannot do without him; but the same God who raised him up, took him from us, and He who has so miraculously prospered our cause, can lead us on without him. Perhaps we have trusted too much to an arm of flesh; for he was the nation’s idol. His soldiers almost worshipped him, and it may be that God has therefore removed him. We bow in meek submission to the great Ruler of events. May his blessed example be followed by officers and men, even to the gates of heaven! He died on Sunday the 10th, at a quarter past three, P. M. His body was carried by yesterday, in a car, to Richmond. Almost every lady in Ashland visited the car, with a wreath or a cross of the most beautiful flowers, as a tribute to the illustrious dead. An immense concourse had assembled in Richmond, as the solitary car containing the body of the great soldier, accompanied by a suitable escort, slowly and solemnly approached the depot. The body lies in state to-day at the Capitol, wrapped in the Confederate flag, and literally covered with lilies of the valley and other beautiful Spring flowers. Tomorrow the sad cortege will wend its way to Lexington, where he will be buried, according to his dying request, in the “Valley of Virginia.” As a warrior, we may appropriately quote from Byron:

“His spirit wraps the dusky mountain,

His memory sparkles o’er the fountain,

The meanest rill, the mightiest river,

Rolls mingling with his fame forever.”

As a Christian, in the words of St. Paul, I thank God to be able to say, “He has fought the good fight, he has finished his course, he has kept the faith. Henceforth there is laid up for him a crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous Judge, shall give him at the last day.”

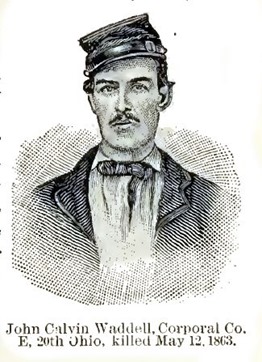

MAY 12TH—Roused up early and before daylight marched, the 20th in the lead. Now we have the honored position, and will probably get the first taste of battle. At nine o’clock slight skirmishing began in front, and at eleven we filed into a field on the right of the road, where another regiment joined us on our right, with two other regiments on the left of the road and a battery in the road itself. In this position our line marched down through open fields until we reached the fence, which we scaled and stacked arms in the edge of a piece of timber. No sooner had we done this than the boys fell to amusing themselves in various ways, taking little heed of the danger about to be entered. A group here and there were employed in “euchre,” for cards seem always handy enough where soldiers are. Another little squad was discussing the scenes of the morning. One soldier picked up several canteens, saying he would go ahead and see if he could fill them. Soon after he disappeared, he returned with a quicker pace and with but one canteen full, saying, when asked why he came back so quick—”while I was filling the canteen I heard a noise, and looking up discovered several Johnnies behind trees, getting ready to shoot, and I concluded I would retire at once and report.” Meanwhile my bedfellow had taken from his pocket a small mirror and was combing his hair and moustache. Said some one to him. “Cal., you needn’t fix up so nice to go into battle, for the rebs won’t think any better of you for it.”

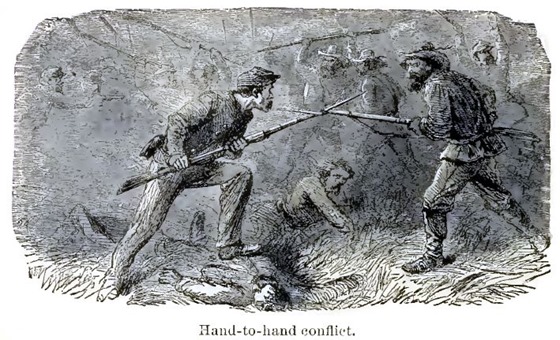

Just here the firing began in our front, and we got orders : “Attention ! Fall in—take arms—forward—double-quick, march!” And we moved quite lively, as the rebel bullets did likewise. We had advanced but a short distance—probably a hundred yards—when we came to a creek, the bank of which was high, but down we slid, and wading through the water, which was up to our knees, dropped upon the opposite side and began firing at will. We did not have to be told to shoot, for the enemy were but a hundred yards in front of us, and it seemed to be in the minds of both officers and men that this was the very spot in which to settle the question of our right of way. They fought desperately, and no doubt they fully expected to whip us early in the fight, before we could get reinforcements. There was no bank in front to protect my company, and the space between us and the foe was open and perfectly level. Every man of us knew it would be sure death to all to retreat, for we had behind us a bank seven feet high, made slippery by the wading and climbing back of the wounded, and where the foe could be at our heels in a moment. However, we had no idea of retreating, had the ground been twice as inviting; but taking in the situation only strung us up to higher determination. The regiment to the right of us was giving way, but just as the line was wavering and about to be hopelessly broken, Logan dashed up, and with the shriek of an eagle turned them back to their places, which they regained and held. Had it not been for Logan’s timely intervention, who was continually riding up and down the line, firing the men with his own enthusiasm, our line would undoubtedly have been broken at some point. For two hours the contest raged furiously, but as man after man dropped dead or wounded, the rest were inspired the more firmly to hold fast their places and avenge the fallen. The creek was running red with precious blood spilt for our

Just here the firing began in our front, and we got orders : “Attention ! Fall in—take arms—forward—double-quick, march!” And we moved quite lively, as the rebel bullets did likewise. We had advanced but a short distance—probably a hundred yards—when we came to a creek, the bank of which was high, but down we slid, and wading through the water, which was up to our knees, dropped upon the opposite side and began firing at will. We did not have to be told to shoot, for the enemy were but a hundred yards in front of us, and it seemed to be in the minds of both officers and men that this was the very spot in which to settle the question of our right of way. They fought desperately, and no doubt they fully expected to whip us early in the fight, before we could get reinforcements. There was no bank in front to protect my company, and the space between us and the foe was open and perfectly level. Every man of us knew it would be sure death to all to retreat, for we had behind us a bank seven feet high, made slippery by the wading and climbing back of the wounded, and where the foe could be at our heels in a moment. However, we had no idea of retreating, had the ground been twice as inviting; but taking in the situation only strung us up to higher determination. The regiment to the right of us was giving way, but just as the line was wavering and about to be hopelessly broken, Logan dashed up, and with the shriek of an eagle turned them back to their places, which they regained and held. Had it not been for Logan’s timely intervention, who was continually riding up and down the line, firing the men with his own enthusiasm, our line would undoubtedly have been broken at some point. For two hours the contest raged furiously, but as man after man dropped dead or wounded, the rest were inspired the more firmly to hold fast their places and avenge the fallen. The creek was running red with precious blood spilt for our  country. My bunkmate[1] and I were kneeling side by side when a ball crashed through his brain, and he fell over with a mortal wound. With the assistance of two others I picked him up, carried him over the bank in our rear, and laid behind a tree, removing from his pocket, watch and trinkets, and the same little mirror that had helped him make his last toilet but a little while before. We then went back to our company after an absence of but a few minutes. Shot and shell from the enemy came over thicker and faster, while the trees rained bunches of twigs around us.

country. My bunkmate[1] and I were kneeling side by side when a ball crashed through his brain, and he fell over with a mortal wound. With the assistance of two others I picked him up, carried him over the bank in our rear, and laid behind a tree, removing from his pocket, watch and trinkets, and the same little mirror that had helped him make his last toilet but a little while before. We then went back to our company after an absence of but a few minutes. Shot and shell from the enemy came over thicker and faster, while the trees rained bunches of twigs around us.

One by one the boys were dropping out of my company. The second lieutenant in command was wounded; the orderly sergeant dropped dead, and I find myself (fifth sergeant) in command of the handful remaining. In front of us was a reb in a red shirt, when one of our boys, raising his gun, remarked, “see me bring that red shirt down,” while another cried out, “hold on, that is my man.” Both fired, and the red shirt fell—it may be riddled by more than those two shots. A red shirt is, of course, rather too conspicuous on a battle field. Into another part of the line the enemy charged, fighting hand to hand, being too close to fire, and using the butts of their guns. But they were all forced to give way at last, and we followed them up for a short distance, when we were passed by our own reinforcements coming up just as we had whipped the enemy. I took the roll-book from the pocket of our dead sergeant, and found that while we had gone in with thirty-two men, we came out with but sixteen—one-half of the brave little band, but a few hours before so full of hope and patriotism, either killed or wounded. Nearly all the survivors could show bullet marks in clothing or flesh, but no man left the field on account of wounds. When I told Colonel Force of our loss, I saw tears course down his cheeks, and so intent were his thoughts upon his fallen men that he failed to note the bursting of a shell above him, scattering the powder over his person, as he sat at the foot of a tree.

Although our ranks have been so thinned by to-day’s battle our will is stronger than ever to march and fight on, and avenge the death of those we must leave behind. I am very sad on account of the loss of so many of my comrades, especially the one who bunked with me, and who had been to me like a brother, even sharing my load when it grew burdensome. He has fallen; may he sleep quietly under the shadows of those old oaks which looked down upon the struggle of to-day.

Although our ranks have been so thinned by to-day’s battle our will is stronger than ever to march and fight on, and avenge the death of those we must leave behind. I am very sad on account of the loss of so many of my comrades, especially the one who bunked with me, and who had been to me like a brother, even sharing my load when it grew burdensome. He has fallen; may he sleep quietly under the shadows of those old oaks which looked down upon the struggle of to-day.

We moved up to the town of Raymond and there camped. I suppose this will be named the battle of Raymond. The citizens had prepared a good dinner for the rebels on their return from victory, but as they actually returned from defeat they were in too much of a hurry to enjoy it. It is amusing now to hear the boys relating their experiences going into battle. All agree that to be under fire without the privilege of returning it is uncomfortable—a feeling which soon wears off when their own firing begins. I suppose the sensations of our boys are as varied as their individualities. No matter how brave a man may be, when he first faces the muskets and cannon of an enemy he is seized with a certain degree of fear, and to some it becomes an occasion of an involuntary but very sober review of their past lives. There is now little time for meditation; scenes change rapidly; he quickly resolves to do better if spared, but when afterward marching from a victorious field such good resolutions are easily forgotten. I confess, with humble pleasure, that I have never neglected to ask God’s protection when going into a fight, nor thanking him for the privilege of coming out again alive. The only thought that troubles me is that of falling into an unknown grave.

The battle to-day opened very suddenly, and when DeGolier’s battery began to thunder, while the infantry fire was like the pattering of a shower, some cooks, happening to be surprised near the front, broke for the rear carrying their utensils. One of them with a kettle in his hand, rushing at the top of his speed, met General Logan, who halted him, asking where be was going, when the cook piteously cried, “Oh General, I’ve got no gun, and such a snapping and cracking as there is up yonder I never heard before.” The General let him pass to the rear.

Thomas Runyan [2], of Company A, was wounded by a musket ball which entered the right eye, and passing behind the left forced it out upon his cheek. As the regiment passed, I saw him lying by the side of the road, tearing the ground in his death struggle.

[1] John Calvin Waddell, Corporal Co. E, 20th Ohio, killed May 12 1863.

[2] When the regiment was being mustered out in July, 1865, Thomas Runyan. who had been left for dead, visited the regiment. He said he came “to see the boys.” He was, of course, totally blind.

12th May (Tuesday).—Shortly after daylight three negroes arrived from Harrisonburg, and they described the fight as still going on. They said they were “dreadful skeered;” and one of them told me he would “rather be a slave to his master all his life, than a white man and a soldier.”

During the morning some of the officers and soldiers left the boat, and determined to cut across country to Harrisonburg, but I would not abandon the scanty remains of my baggage until I was forced to do so.

During the morning twelve more negroes arrived from Harrisonburg. It appears that three hundred of them, the property of neighbouring planters, had been engaged working on the fortifications, but they all with one accord bolted when the first shell was fired. Their only idea and hope at present seemed to be to get back to their masters. All spoke of the Yankees with great detestation, and expressed wishes to have nothing to do with such “bad people.”

Our captain coolly employed them in tearing down the fences, and carrying the wood away on board the steamer for firewood.

We did nothing but this all day long, the captain being afraid to go on, and unwilling to return. In the evening a new alarm seized him—viz., that the Federal cavalry had cut off the Confederate line of couriers.

During the night we remained in the same position as last night, head up stream, and ready to be off at a moment’s notice.[1]

[1] One of the passengers on board this steamer was Captain Barney of the Confederate States Navy, who has since, I believe, succeeded Captain Maffit in the command of the Florida.

Mrs. Lyon’s Diary.

May 12.—Had a great time last night. Had to change boats and took the Prairie Maid. Had several hours this morning and went into the city. Called on the Chief of Ordinance, Captain Townsend. Went back to the boat after strolling around all we wanted to, and started for Fort Donelson. Got to Clarksville and went into the city to the college, now used for a hospital.

Tuesday, 12th—We took up our march at 5 o’clock this morning and marched sixteen miles over very fine roads. This is a very rich country, and before the war, was prosperous, but now looks quite desolate, the buildings and fences having been burned by our troops. At the approach of our army the people fled, leaving all behind them. At noon we halted for lunch, and since it was so fearfully hot, remained here during the heat of the day in the shade of evergreens. The Eleventh Iowa was situated just opposite the residence of General Bowie, said to be a descendant of the inventor of the bowie knife. The main Bowie residence was burned and household articles, among which is a grand piano, are strewn about the large lawn. The outbuildings, on a grand scale, were not molested. The lawn contains about forty acres and is planted in all kinds of tropical trees and shrubbery, with cisterns and fountains at different points. The plantation borders the west bank of Lake St. Joseph, the public highway being just between it and the lake. This plantation, containing several thousand acres, is all planted to corn, which is now in tassel and silk. Our march today was along the west bank of the lake with a continuous cornfield on our right. When night came we were still by the lake, where we went into bivouac.

Private Jacob Harker of Company C, 120th Ohio Volunteers in uniform with musket and haversack; identification based on note inside case: Pvt. Jacob Harker, Co. C, 120th Ohio Vol. died May 1863 of diarrhea, N.O., La.

sixth-plate tintype, hand-colored ; 9.5 x 8.3 cm (case)

Donated by Tom Liljenquist; 2012

Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs; Ambrotype/Tintype photograph filing series; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Record page for image is here.

__________

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

- fade correction,

- color, contrast, and/or saturation enhancement

- selected spot removal.

Civil War Portrait 032

May 12, Tuesday. We have information that Stonewall Jackson, one of the best generals in the Rebel, and, in some respects, perhaps in either, service, is dead. One cannot but lament the death of such a man, in such a cause too. He was fanatically earnest, and a Christian but bigoted soldier.

A Mr. Prentiss has presented a long document to the President for the relief of certain parties who owned the John Gilpin, a vessel loaded with cotton, and captured and condemned as good prize. There has been a good deal of outside engineering in this case. Chase thought if the parties were loyal it was a hard case. I said all such losses were hard, and asked whether it was hardest for the wealthy, loyal owners, who undertook to run the blockade with their cotton, or the brave and loyal sailors who made the capture and were by law entitled to the avails, to be deprived. I requested him to say which of these parties should be the losers. He did not answer. I added this was another of those cases that belonged to the courts exclusively, with which the Executive ought not to interfere. All finally acquiesced in this view.

This case has once before been pressed upon the President. Senator Foot of Vermont appeared with Mr. Prentiss, and the President then sent for me to ascertain its merits. I believe I fully satisfied him at that time, but his sympathies have again been appealed to by one side.

Mr. Seward came to my house last evening and read a confidential dispatch from Earl Russell to Lord Lyons, relative to threatened difficulties with England and the unpleasant condition of affairs between the two countries. He asked if anything could be done with Wilkes, whom he has hitherto favored, but against whom the Englishmen, without any sufficient cause, are highly incensed. I told him he might be transferred to the Pacific, which is as honorable but a less active command; that he had favored Wilkes, who was not one of the most comfortable officers for the Navy Department. I was free to say, however, I had seen nothing in his conduct thus far, in his present command, towards the English deserving of censure, and that the irritation and prejudice against him were unworthy, yet under the peculiar condition of things, it would perhaps be well to make this concession. I read to him an extract from a confidential letter of J. M. Forbes, now in England, a most earnest and sincere Union man, urging that W. should be withdrawn, and quoting the private remarks of Mr. Cobden to that effect. I had read the same extract to the President last Friday evening, Mr. Sumner being present. He (Sumner) remarked it was singular, but that he had called on the President to read to him a letter which he had just received from the Duke of Argyle, in which he advised that very change. This letter Sumner has since read to me. It is replete with good sense and good feeling.

I have to-day taken preliminary steps to transfer Wilkes and to give Bell command in the West Indies. It will not surprise me if this, besides angering Wilkes, gives public discontent. His strange course in taking Slidell and Mason from the Trent was popular, and is remembered with gratitude by the people, who are not aware his work was but half done, and that, by not bringing in the Trent as prize, he put himself and the country in the wrong. Seward at first approved the course of Wilkes in capturing Slidell and Mason, and added to my embarrassment in so disposing of the question as not to create discontent by rebuking Wilkes for what the country approved. But when, under British menace, Seward changed his position, he took my position, and the country gave him great credit for what was really my act and the undoubted law of the case. My letter congratulating Wilkes on the capture of the Rebel enemies was particularly guarded and warned him and naval officers against a similar offense. The letter was acceptable to all parties, — the Administration, the country, and even Wilkes was contented.

It is best under the circumstances that Wilkes should be withdrawn from the West Indies, where he was sent by Seward’s special request, unless, as he says, we are ready for a war with England. I sometimes think that is not the worst alternative, she behaves so badly.