12th. Sent a letter to Minnie. Played chess with Chester and Lt. Case, on the whole did well. Short talk with Bushnell. Could have done better in Arkansas. Let our horses into a field to graze. Read the Commercial of the 10th, some in Gazette. Drove up a beef from town.

Sunday, May 12, 2013

Tuesday, 12th—I and Will Rogers went over to Green’s and Bass’s; met by John M. Green getting in. Met Albright, went back to D’s and stay all night. S. K. there.

May 12. — Weather very warm. Went down to General Griffin’s and took dinner there. Went to my regiment, to General Barnes, and to the 22d, and stopped at General Meade’s headquarters on my way back. Found that Captain Clapp and Captain Strang had gone to Washington, and that I should have to act as acting assistant adjutant-general.

“Head-Quarters Major-General McPherson, May 13, 1863

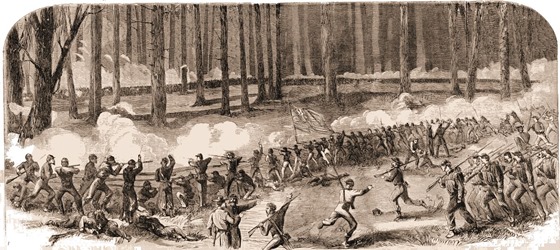

“At 10 o’clock on the 12th the ‘Body Guard,’ under Captain Foster, discovered the enemy in small force upon the road three miles from Raymond. A portion of General Dennis’s brigade—the Twentieth Ohio and Thirtieth Illinois Regiments —were deployed to the right and left of the road. Being advanced, the enemy were discovered in line of battle, occupying a commanding position, a mile and a half from Raymond.

“A section of De Golyer’s battery was placed in position in the road, and at a distance of one thousand yards opened the fight, when the whole battery was placed in position, with the brigade of General Dennis for its support, it being in turn supported by the brigades of Generals Smith and Stevenson, who soon after formed in line of battle upon the right. These troops, constituting General Logan’s division, were soon charged by the enemy. The charge was upon the right flank, but the previous disposition of troops frustrated it, and a sharp engagement of an hour ensued. The enemy were repulsed.

“General Crocker’s division coming up, was disposed to the right, left, and reserve by General McPherson, and the line immediately advanced. The rebels, being driven from their position, retreated through the town toward Jackson. and our troops occupied Raymond. Our loss was 52 killed and 198 wounded. Among the killed was Coloneel Richards. Colonel McCook was wounded.

May 12th. The troops are in good condition again, fully recovered from the late mud campaign and waiting for some thing to turn up. In the meantime, the men, at least some of them, are gardening again, and the seeds planted early are, in fact, up and growing fast. Many changes have occurred amongst the commanding officers. Couch is to leave us, as we hear, on account of his distaste for present commanders. He has served with the Second corps since Sumner retired and is a very quiet, sensible, competent officer, but looks more like a Methodist minister than a soldier. Our own gallant Hancock takes the corps’ command, and Brigadier-General John C. Caldwell, now commanding the First brigade, will assume command of the division. Hooker’s successor has not been heard from so far, but, of course, he will not be retained in command.

by John Beauchamp Jones

MAY 12TH.—The departments and all places of business are still closed in honor of Gen. Jackson, whose funeral will take place to-day. The remains will be placed in state at the Capitol, where the people will be permitted to see him. The grief is universal, and the victory involving such a loss is regarded as a calamity.

The day is bright and excessively hot; and so was yesterday.

Many letters are coming in from the counties in which the enemy’s cavalry replenished their horses. It appears that the government has sent out agents to collect the worn-down horses left by the enemy; and this is bitterly objected to by the farmers. It is the corn-planting season, and without horses, they say, they can raise no crops. Some of these writers are almost menacing in their remarks, and intimate that they are about as harshly used, in this war, by one side as the other.

To-day I observed the clerks coming out of the departments with chagrin and mortification. Seventy-five per cent. of them ought to be in the army, for they are young able-bodied men. This applies also to the chiefs of bureaus.

The funeral was very solemn and imposing, because the mourning was sincere and heartfelt. There was no vain ostentation. The pall bearers were generals. The President followed near the hearse in a carriage, looking thin and frail in health. The heads of departments, two and two, followed on foot—Benjamin and Seddon first—at the head of the column of young clerks (who ought to be in the field), the State authorities, municipal authorities, and thousands of soldiers and citizens. The war-horse was led by the general’s servant, and flags and black feathers abounded.

Arrived at the Capitol, the whole multitude passed the bier, and gazed upon the hero’s face, seen through a glass in the coffin.

Just previous to the melancholy ceremony, a very large body of prisoners (I think 3500) arrived, and were marched through Main Street, to the grated buildings allotted them. But these attracted slight attention,—Jackson, the great hero, was the absorbing thought. Yet there are other Jacksons in the army, who will win victories,—no one doubts it.

The following is Gen. Lee’s order to the army after the intelligence of Gen. Jackson’s death : [click to continue…]

May 12.—A force of National troops under the command of Colonel Davis, First Texas cavalry, left Sevieck’s Ferry, on the Amite River, La., on an expedition along the Jackson Railroad. They struck the railroad at Hammond Station, where they cut the telegraph and burned the bridge.— New-Orleans Era.

—A party of sixty mounted rebels were encountered at a point between Woodburn and Franklin, Ky., by a detachment of Union troops, who defeated them and put them to flight.

—S. L. Phelps, commanding the Tennessee division of the Mississippi squadron, took on board his gunboats fifty-five men and horses of the First Western Tennessee cavalry, under the command of Colonel W. K. M. Breckinridge, and landed them on the east side of the Tennessee River, sending the gunboats to cover all the landings above and below. Colonel Breckinridge dashed across the country to Linden, and surprised a rebel force more than twice his number, capturing Lieutenant-Colonel Frierson, one captain, one surgeon, four lieutenants, thirty rebel soldiers, ten conscripts, fifty horses, two army wagons, arms, etc. The court-house, which was the rebel depot, was burned, with a quantity of army supplies. The enemy lost three killed. The Nationals lost no men, but had one horse killed. Colonel Breckinridge, after this exploit, reached the vessel in safety, and recrossed the river.— Com. Phelps’s Despatch.

—The battle of Raymond, Miss., was fought this day, between the rebels under General Gregg, and the Union troops commanded by General McPherson.— (Doc. 190.)

Camp of 1st Mass. Cav’y

Potomac Creek, May 12, 1863

It is by no means a pleasant thought to reflect how little people at home know of the non-fighting details of waste and suffering of war. We were in the field four weeks, and only once did I see the enemy, even at a distance. You read of Stoneman’s and Grierson’s cavalry raids, and of the dashing celerity of their movements and their long, rapid marches. Do you know how cavalry moves? It never goes out of a walk, and four miles an hour is very rapid marching — “killing to horses” as we always describe it. To cover forty miles is nearly fifteen hours march. The suffering is trifling for the men and they are always well in the field in spite of wet and cold and heat, loss of sleep and sleeping on the ground. In the field we have no sickness; when we get into camp it begins to appear at once.

But with the horses it is otherwise and you have no idea of their sufferings. An officer of cavalry needs to be more horse-doctor than soldier, and no one who has not tried it can realize the discouragement to Company commanders in these long and continuous marches. You are a slave to your horses, you work like a dog yourself, and you exact the most extreme care from your Sergeants, and you see diseases creeping on you day by day and your horses breaking down under your eyes, and you have two resources, one to send them to the reserve camps at the rear and so strip yourself of your command, and the other to force them on until they drop and then run for luck that you will be able to steal horses to remount your men, and keep up the strength of your command. The last course is the one I adopt. I do my best for my horses and am sorry for them; but all war is cruel and it is my business to bring every man I can into the presence of the enemy, and so make war short. So I have but one rule, a horse must go until he can’t be spurred any further, and then the rider must get another horse as soon as he can seize on one. To estimate the wear and tear on horseflesh you must bear in mind that, in the service in this country, a cavalry horse when loaded carries an average of 225 lbs. on his back. His saddle, when packed and without a rider in it, weighs not less than fifty pounds. The horse is, in active campaign, saddled on an average about fifteen hours out of the twenty four. His feed is nominally ten pounds of grain a day and, in reality, he averages about eight pounds. He has no hay and only such other feed as he can pick up during halts. The usual water he drinks is brook water, so muddy by the passage of the column as to be of the color of chocolate. Of course, sore backs are our greatest trouble. Backs soon get feverish under the saddle and the first day’s march swells them; after that day by day the trouble grows. No care can stop it. Every night after a march, no matter how late it may be, or tired or hungry I am, if permission is given to unsaddle, I examine all the horses’ backs myself and see that everything is done for them that can be done, and yet with every care the marching of the last four weeks disabled ten of my horses, and put ten more on the high road to disability, and this out of sixty — one horse in three. Imagine a horse with his withers swollen to three times the natural size, and with a volcanic, running sore pouring matter down each side, and you have a case with which every cavalry officer is daily called upon to deal, and you imagine a horse which has still to be ridden until he lays down in sheer suffering under the saddle. Then we seize the first horse we come to and put the dismounted man on his back. The air of Virginia is literally burdened today with the stench of dead horses, federal and confederate. You pass them on every road and find them in every field, while from their carrions you can follow the march of every army that moves.

On this last raid dying horses lined the road on which Stoneman’s divisions had passed, and we marched over a road made pestilent by the dead horses of the vanished rebels. Poor brutes! How it would astonish and terrify you and all others at home with your sleek, well-fed animals, to see the weak, gaunt, rough animals, with each rib visible and the hip-bones starting through the flesh, on which these “dashing cavalry raids” were executed. It would knock the romance out of you. So much for my cares as a horse-master, and they are the cares of all. For, I can safely assure you, my horses are not the worst in the regiment and that I am reputed no unsuccessful chief-groom. I put seventy horses in the field on the 13th of April, and not many other Captains in the service did as much. . . .

The present great difficulty is to account for our failure to win a great victory and to destroy the rebel army in the recent battle. They do say that Hooker got frightened and, after Sedgwick’s disaster, seemed utterly to lose the capacity for command — he was panic stricken. Two thirds of his army had not been engaged at all, and he had not heard from Stoneman, but he was haunted with a vague phantom of danger on his right flank and base, a danger purely of his own imagining, and he had no peace until he found himself on this side of the river. Had he fought his army as he might have fought it, the rebel army would have been destroyed and Richmond today in our possession. We want no more changes, however, in our commanders, and the voice of the Army, I am sure, is to keep Hooker; but I am confident that he is the least respectable and reliable and I fear the least able commander we have had. I never saw him to speak to, but I think him a noisy, low-toned intriguer, conceited, intellectually “smart,” physically brave. Morally, I fear, he is weak; his habits are bad and, as a general in high command, I have lost all confidence in him. But the army is large, brave and experienced. We have many good generals and good troops, and, in spite of Hooker, I think much can be done if we are left alone. Give us no more changes and no new generals!

As for the cavalry, its future is just opening and great names will be won in the cavalry from this day forward. How strangely stupid our generals and Government have been! How slow to learn even from the enemy! Here the war is two years old and throughout it we have heard but one story — that in Virginia cavalry was useless, that the arm was the poorest in the service. Men whom we called generals saw the enemy’s cavalry go through and round their armies, cutting their lines of supply and exposing their weakness; and yet not one of these generals could sit down and argue thus: “The enemy’s cavalry almost ruin me, and I have only a few miles of base and front, all of which I can guard; but the enemy has here in Virginia thousands of miles of communication; they cannot guard it without so weakening their front that I can crush them; if they do not guard it, every bridge is a weak point and I can starve them by cutting off supplies. My cavalry cannot travel in any direction without crossing a railroad, which the enemy cannot guard and which is an artery of their existence. A rail pulled up is a supply train captured. Give me 25,000 cavalry and I will worry the enemy out of Virginia.” None of our generals seem to have had the intelligence to argue thus and so they quietly and as a fixed fact said: “Cavalry cannot be used in Virginia,” and this too while Stuart and Lee were playing around them. And so they paralyzed their right arm. Two years have taught them a simple lesson and today it is a recognized fact that 25,000 well appointed cavalry could force the enemy out of Virginia. How slow we are as a people to learn the art of war! Still, we do learn.

But the troubles of the cavalry are by no means over. Hooker, it is said, angrily casting about for some one to blame for his repulse, has, of all men, hit upon Stoneman. Why was not Stoneman earlier? Why did not he take Richmond? and they do say Hooker would deprive him of his command if he dared. Meanwhile, if you follow the newspapers, you must often have read of one Pleasonton and his cavalry. Now Pleasonton is the bete noire of all cavalry officers. Stoneman we believe in. We believe in his judgment, his courage and determination. We know he is ready to shoulder responsibility, that he will take good care of us and won’t get us into places from which he can’t get us out. Pleasonton also we have served under. He is pure and simple a newspaper humbug. You always see his name in the papers, but to us who have served under him and seen him under fire he is notorious as a bully and toady. He does nothing save with a view to a newspaper paragraph. At Antietam he sent his cavalry into a hell of artillery fire and himself got behind a bank and read a newspaper, and there, when we came back, we all saw him and laughed among ourselves. Yet mean and contemptible as Pleasonton is, he is always in at Head Quarters and now they do say that Hooker wishes to depose Stoneman and hand the command over to Pleasonton. You may imagine our sensations in prospect of the change. Hooker is powerful, but Stoneman is successful. . . .