May 14. — Weather was much cooler to-day. Very windy at night. Went over to headquarters in the evening. John Perry came over here to lunch. Two wrens have been building a nest in my stove-pipe for the past two days; they are quite tame, and come to the door of my tent to pick up rags, etc.

Tuesday, May 14, 2013

May 14th. Commences, “for a change,” with stormy weather, squalls of rain, and continued so during forenoon of this day; at seven A. M. the despatch steamer L. A. Sykes came out of Red River, direct from Alexandria, and made fast alongside of us, bringing despatches from Gen. Banks to Commodore Palmer; also the gunboat Sachem arrived; at seven thirty the Sykes got under way and went up Red river. This is a fine and fast little steamer, and is of great service to us; at six forty five P. M. the U. S. steamer Arizona came down and out of Red River, with Brig.-Gen. Dwight as a passenger, on his way to Grand Gulf to take command of some of Gen. Banks’s forces there. He came on board and paid his respects to Commodore Palmer. Let me here remark that this gentleman and soldier but a short time since had a brother killed near Alexandria by some guerrillas, while in the performance of his duty, whose loss he feels very much. He was a Captain in the army, and at the time he was killed was carrying despatches from Gen. Banks to some part of his command, and was mounted, but unarmed; at seven P. M. the Arizona steamed on her way up the river, bound to Grand Gulf. Nothing more of importance occurred during the remainder of these twenty-four hours.

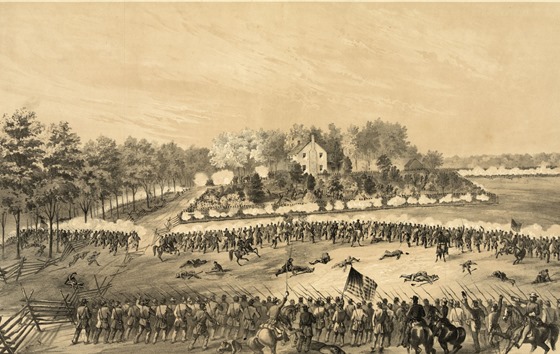

Lithograph by Middleton, Strobridge & Co. Lith. Cin. O.

“Battle of Jackson, Mississippi–Gallant charge of the 17th Iowa, 80th Ohio and 10th Missouri, supported by the first and third brigades of the seventh division / sketched by A.E. Mathews, 31st Reg., O.V.I.”

Library of Congress image.

by John Beauchamp Jones

MAY 14TH.—We have been beaten in an engagement near Jackson, Miss., 4000 retiring before 10,000. This is a dark cloud over the hopes of patriots, for Vicksburg is seriously endangered. Its fall would be the worst blow we have yet received.

MAY 14TH.—We have been beaten in an engagement near Jackson, Miss., 4000 retiring before 10,000. This is a dark cloud over the hopes of patriots, for Vicksburg is seriously endangered. Its fall would be the worst blow we have yet received.

Papers from New York and Philadelphia assert most positively, and with circumstantiality, that Hooker recrossed the Rappahannock since the battle, and is driving Lee toward Richmond, with which his communications have been interrupted. But this is not all: they say Gen. Keyes marched a column up the Peninsula, and took Richmond itself, over the Capitol of which the Union flag is now flying.” These groundless statements will go out to Europe, and may possibly delay our recognition. If so, what may be the consequences when the falsehood is exposed? I doubt the policy of any species of dishonesty.

Gov. Shorter, of Alabama, demands the officers of Forrest’s captives for State trial, as they incited the slaves to insurrection.

Mr. S. D. Allen writes from Alexandria, La., that the people despair of defending the MississippiValley with such men as Pemberton and other hybrid Yankees in command. He denounces the action also of quartermasters and commissaries in the Southwest.

A letter from Hon. W. Porcher Miles to the Secretary of War gives an extract from a communication written him by Gen. Beauregard, to the effect that Charleston must at last fall into the hands of the enemy, if an order which has been sent there, for nearly all his troops to proceed to Vicksburg, be not revoked. There are to be left for the defense of Charleston only 100 exclusive of the garrisons!

May 14.—Jackson, Miss., was captured by the National forces belonging to the army of General Grant, after a fight of over three hours. General Joseph E. Johnston was in command of the rebels, who retreated toward the north.—(Doc. 191.)

—To-day a detachment of the National expeditionary force under Colonel Davis, destroyed the tannery, grist, and saw-mill, together with a steam-engine, at Hammond Station, on the Jackson Railroad, La.—New-Orleans Era.

—A scouting-party of National troops, sent out from Fairfax Court-House, Va., encountered a small force of the Black Horse cavalry, at the house of Mr. Masilla, five miles beyond Warrenton Junction, when a skirmish ensued, resulting in the dispersion of the rebels, the death of Mr. Masilla, and the wounding of several other rebels. The Nationals had three wounded.—New-York Tribune.

Adams Family Letters, Henry Adams, private secretary of the US Minister to the UK, to his brother, Charles.

London, May 14, 1863

The telegraph assures us that Hooker is over the Rappahannock and your division regally indistinct “in the enemy’s rear.” I suppose the campaign is begun, then. Honestly, I’d rather be with you than here, for our state of mind during the next few weeks is not likely to be very easy.

But now that things are begun, I will leave them to your care. Just for your information, I inclose one of Mr. Lawley’s letters from Richmond to the London Times. It is curious. Mr. Lawley’s character here is under a cloud, as, strange to say, is not unusual with the employes of that seditious journal. For this and other reasons I don’t put implicit trust in him, but one fact is remarkably distinct. His dread of the shedding of blood makes him wonderfully anxious for intervention. A prayer for intervention is all that the northern men read in this epistle, and Mr. Lawley’s humanity does n’t quite explain his earnestness. . . .

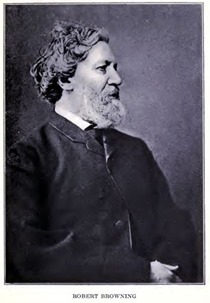

It was a party of only eleven, and of these Sir Edward [Lytton] was one, Robert Browning another, and a Mr. Ward, a well known artist and member of the Royal Academy, was a third. All were people of a stamp, you know; as different from the sky-blue, skim-milk of the ball-rooms, as good old burgundy is from syrup-lemonade. I had a royal evening; a feast of remarkable choiceness, for the meats were very excellent good, the wines were rare and plentiful, and the company was of earth’s choicest.

Sir Edward is one of the ugliest men it has been my good luck to meet. He is tall and slouchy, careless in his habits, deaf as a ci-devant, mild in manner, and quiet and philosophic in talk. Browning is neat, lively, impetuous, full of animation, and very un-English in all his opinions and appearance. Here, in London Society, famous as he is, half his entertainers actually take him to be an American. He told us some amusing stories about this, one evening when he dined here.

Sir Edward is one of the ugliest men it has been my good luck to meet. He is tall and slouchy, careless in his habits, deaf as a ci-devant, mild in manner, and quiet and philosophic in talk. Browning is neat, lively, impetuous, full of animation, and very un-English in all his opinions and appearance. Here, in London Society, famous as he is, half his entertainers actually take him to be an American. He told us some amusing stories about this, one evening when he dined here.

Just to amuse you, I will try to give you an idea of the conversation after dinner; the first time I have ever heard anything of the sort in England. Sir Edward is a great smoker, and although no crime can be greater in this country, our host produced cigars after the ladies had left, and we filled our claret-glasses and drew up together.

Sir Edward seemed to be continuing a conversation with Mr. Ward, his neighbor. He went on, in his thoughtful, deliberative way, addressing Browning.

“Do you think your success would be very much more valuable to you for knowing that centuries hence, you would still be remembered? Do you look to the future connection by a portion of mankind, of certain ideas with your name, as the great reward of all your labor?”

“Not in the least! I am perfectly indifferent whether my name is remembered or not. The reward would be that the ideas which were mine, should live and benefit the race!”

“I am glad to hear you say so,” continued Sir Edward, thoughtfully, “because it has always seemed so to me, and your opinion supports mine. Life, I take to be a period of preparation. I should compare it to a preparatory school. Though it is true that in one respect the comparison is not just, since the time we pass at a preparatory school bears an infinitely greater proportion to a life, than a life does to eternity. Yet I think it may be compared to a boy’s school; such a one as I used to go to, as a child, at old Mrs. S’s at Fulham. Now if one of my old school-mates there were to meet me some day and seem delighted to see me, and asked me whether I recollected going to old mother S’s at Fulham, I should say, ‘Well, yes. I did have some faint remembrance of it! Yes. I could recollect about it.’ And then supposing he were to tell me how I was still remembered there! How much they talked of what a fine fellow I’d been at that school.”

“How Jones Minimus,” broke in Browning, “said you were the most awfully good fellow he ever saw.”

“Precisely,” Sir Edward went on, beginning to warm to his idea. “Should I be very much delighted to hear that? Would it make me forget what I am doing now? For five minutes perhaps I should feel gratified and pleased that I was still remembered, but that would be all. I should go back to my work without a second thought about it.

“Well now, Browning, suppose you, sometime or other, were to meet Shakespeare, as perhaps some of us may. You would rush to him and seize his hand, and cry out, ‘My dear Shakespeare, how delighted I am to see you. You can’t imagine how much they think and talk about you on the earth!’ Do you suppose Shakespeare would be more carried away by such an announcement than I should be at hearing that I was still remembered by the boys at mother S’s at Fulham? What possible advantage can it be to him to know that what he did on the earth is still remembered there?”

The same idea is in LXII of Tennyson’s In Memoriam, but not pointed the same way. It was curious to see two men who, of all others, write for fame, or have done so, ridicule the idea of its real value to them. But Browning went on to get into a very unorthodox humor, and developed a spiritual election that would shock the Pope, I fear. According to him, the minds or souls that really did develope themselves and educate themselves in life, could alone expect to enter a future career for which this life was a preparatory course. The rest were rejected, turned back, God knows what becomes of them, these myriads of savages and brutalized and degraded Christians. Only those that could pass the examination were allowed to commence the new career. This is Calvin’s theory, modified; and really it seems not unlikely to me. Thus this earth may serve as a sort of feeder to the next world, as the lower and middle classes here do to the aristocracy, here and there furnishing a member to fill the gaps. The corollaries of this proposition are amusing to work out.

MAY 14TH.—Started again this morning for Jackson. When within five miles of the city we heard heavy firing. It has rained hard to-day and we have had both a wet and muddy time, pushing at the heavy artillery and provision  wagons accompanying us when they stuck in the mud. The rain came down in perfect torrents. What a sight ! Ambulances creeping along at the side of the track—artillery toiling in the deep ruts, while Generals with their aids and orderlies splashed mud and water in every direction in passing. We were all wet to the skin, but plodded on patiently, for the love of country.

wagons accompanying us when they stuck in the mud. The rain came down in perfect torrents. What a sight ! Ambulances creeping along at the side of the track—artillery toiling in the deep ruts, while Generals with their aids and orderlies splashed mud and water in every direction in passing. We were all wet to the skin, but plodded on patiently, for the love of country.

When within a few miles of Jackson, the news reached us that Sherman had slipped round to the right and captured the place, and the shout that went up from the men on the receipt of that news was invigorating to them in the midst of trouble. I think they could have been heard in Jackson. Sherman’s army at the right and McPherson in our immediate front, with one desperate charge we ran without stopping till we reached the town. The flower of the confederate forces, the pride of the Southern States who had never yet known defeat, came up to Jackson last night to help demolish Grant’s army, but for once they failed. Veterans of Georgia stationed as reserves were also forced to yield in dismay, and never stopped retreating till they had passed far south of the Capital which they had striven so valiantly to defend. To-night the stars and stripes float proudly over the cupola of the seat of government of Mississippi—and if my own regiment has not had a chance to-day to cover itself with glory it has with mud.

I shall not soon forget the conversation I have had with a wounded rebel. He said that his regiment last night was full of men who had never before met us, and who felt sure it would be easy to whip us. How they were deceived! He said part of his regiment was behind a hedge fence, where they felt comparatively safe, but the Yankees jumped right over without stopping, and swept everything before them. I never saw finer looking men than the killed and wounded rebels of to-day, and with the smooth face of one of them, lying in a garden mortally wounded, I was so taken, that I eased his thirst with a drink from my own canteen. His piteous glance at me at that time I shall never forget. It is on the battle field and among the dead and dying we get to know each other better—nay, even our own selves. Administering to a stranger, we think of his mother’s love, as dear to him as our own to us. When the fight is over, away all bitterness. Let us leave with the foe some tokens of good will, that, when the cruel war at last is over, may be kindly remembered. I trust our enemies may yet be led to hail in good faith the return of peace and the restoration of the Union. This is a domestic war, the saddest of all, being fought between those whose hearts should be as brothers; and when it is at an end, may those hearts again throb together beneath the folds of the flag that once waved for defence over their sires and themselves —a flag whose proud motto will be, “peace on earth and good will to men.”

Some of the boys went down into the city to view our new possession. It seems ablaze, but I trust only public property is being destroyed, or such as might aid and comfort the enemy hereafter.

I am very tired, and of course can easily get excused, so I will go to my bed on the ground.

May 14. — A gentle rain is pattering on the tent-roof, — grateful to us now as a shower in August in Northern city or hamlet. To its soothing music the other men have gone to sleep; while I sit here with my back to the tent-pole, writing words to this pretty pattering tune. May is going; and we are, generally speaking, as idle here as during the previous month we were active. It is nearly three weeks since we encamped on the Courtableau, — weeks of glorious summer. Day and night, along the bayou, the mocking-bird “shakes from his little throat whole floods of delirious music;” and over the stream, from the boughs of the big trees, hang the ladders of moss, — the Jacob’s ladders, on which “the angels, ascending, descending, are the swift humming-birds.” The distant forest line is blue to the eye, and of impenetrable density. What enchanter’s incense is this sweet blue haze! lulling the outer sense, stimulating the fancy; so that I sit under our booth, my eyes upon the far-away woods, dreaming of romance,—just now of the “wood of Broceliande,” and Vivien charming Merlin with her spells “of woven paces and of waving arms.” O sweet “Idyls of the King”! is there any poetry like you? It is all beautiful. But our sojourn here is inglorious. Instead of being left behind to guard cotton, I would have preferred to march with Banks to the Red River: a cup of fatigue and hardship it would have been, but gloriously dashed with excitement.

The pile of cotton is a mountain on the landing. All day long, — every day for weeks, — teams have brought it in, until it almost seems worth while to build here the factories that are to work it up into fabric; but, since Mahomet will not come to the mountain (to set on its head the saying), the mountain is going to Mahomet. Down it goes, piecemeal, through the bayou, on little steamers padded out like lank belles, at every available place, into portentous embonpoint. They say our business here will be finished when the cotton is carried away: so we watch the slow decrease of the pile, hear the mocking-birds, wash lazily in the bayou in contempt of alligators, and live along.

Along the bank of the stream is an immense camp of negroes. They have come by thousands from the whole country round. Generally, their masters appear to have fled; and the negroes, harnessing up the mules, loading in their families together with their own and their masters’ goods, have come crowding in to us. They come trustingly, rejoicing in their freedom. By night, until long past midnight sometimes, we can hear them shout, pray, and sing. Gen. Ullman has been here, and the able-bodied men are to become soldiers. The women and older men, and all not fit for military duty, are to go on to plantations taken by the Government or by loyal men. They are to receive wages, and be well cared for. No doubt, their condition will be distressing in many cases. For them, it is a most momentous period of transition, — a crisis which they can hardly pass without suffering; but it will be temporary, and a bright future lies before them.

The other day, on the bank of the bayou, I found a man, born, as he said, in New Jersey. He came South as steward of a ship, and was coolly sold by his captain into slavery at New Orleans. From there he became a plantation-hand, and for fifteen years had been in bondage.

Last week, there came shivering through to us from Port Hudson, forty miles away, the boom of a mighty bombardment. We heard them, Friday and Saturday, getting the range; then Saturday night, —it was starlight, and all calm as an infant’s sleep, — that night we heard the roar of the real attack, — continuous thunder from the far north-east. We could tell the sharp reports of the Parrotts, the heavier boom of Dahlgren, the long-drawn crash of mortar. The whole air listened; and the land trembled, as if it partook in the guilt of its inhabitants, and quailed beneath the blasting and thunderous retribution that was falling. We felt it, rather than heard it, all through the long night, coming through desolate fen and over plain, through wood and over stream; imparting tremor to every foot in those dreary, intervening leagues, as if the Genius of the conquering North were making the land feel everywhere the -indignant stamp of her resistless heel!

So we live and listen and wait. I am reduced now to about the last stage. My poor blouse grows raggeder. My boots, as boys say, are hungry in many places. I have only one shirt; and that has shrunk about the neck, until buttons and button-holes are irretrievably divorced, and cannot be forced to meet. Washing-days, if I were anywhere else, I should have to lie abed until the washer-woman brought home the shirt. Now I cannot lie abed, for two reasons: first, I am washer-woman myself; second, the bed is only bed at night. By daytime, it is parlor-floor, divan, dining-table, and library, and therefore taken up. I button up in my blouse, therefore; and can so fix myself, and so brass matters through, that you would hardly suspect, unless you looked sharp, what a whited sepulchre it was that stood before you. I have long been without a cup. Somebody stole mine long ago; and I, unfortunate for me, am deterred, by the relic of a moral scruple which still lingers in my breast, from stealing somebody else’s in return. My plate is the original Camp-Miller tin plate, worn down now to the iron. I have leaned and lain and stood on it, until it looks as if it were in the habit of being used in the exhibitions of some strong man, who rolled it up and unrolled it to show the strength of his fingers. There is a big crack down the side; and, soup-days, there is a great rivalry between that crack and my mouth, —the point of strife being, which shall swallow most of the soup; the crack generally getting the best of it.

Rations pall now-a-days. The thought of soft bread is an oasis in the memory. Instead of that, our wearied molars know only hard-tack, and hard salt beef and pork. We pine for simple fruits and vegetables. The other day, however, I received a gift. An easy-conscienced friend of mine brought in a vast amount of provender from a foraging expedition, and bestowed upon me a superb turkey, — the biggest turkey I ever saw; probably the grandfather of his whole race. His neck and breast were decorated with a vast number of red and purple tassels and trimmings. He was very fat, moreover; so that he looked like an apoplectic sultan. I carried him home with toil and sweat; but what to do with him for the night! If he had been left outside, he would certainly have been stolen: so the only way was to make a bedfellow of him. Occasionally he woke up, and “gobbled;” and I feared all night long the peck of his bill and the impact of his spurs. In the morning, we immolated him with appropriate ceremonies. The chaplain’s coal-hod, the best thing in camp to make a soup in, was in use; but I found a kettle, and presided over the preparation of an immense and savory stew, the memory whereof will ever steam up to me from the past with grateful sweetness.

In spite of hard fare, I appear to flourish. The other day, I thought I was afflicted with some strange and terrible disease. I was growing short-winded, and had a novel fulness about the waist, which tightened my vest-buttons. Yesterday, however, I was weighed, and found myself fourteen or fifteen pounds beyond my usual weight. I was short-winded only because I was pursy; and the protuberant stomach was simply adipose. My gait, too, I thought was affected. Alas! is it simply that I waddle?