23rd.—We tremble for Vicksburg; an immense army has been sent against it; we await its fate with breathless anxiety.

Thursday, May 23, 2013

May 23d. After an uneventful ride we arrived at Sandy Hook at four o’clock this morning, getting our first view of the Potomac River. Orders received to turn out and form in line for a march. The road was along the side of the Ohio and Chesapeake Canal, under the Maryland Heights. The march continued on over the iron railroad bridge crossing the Potomac River into Harper’s Ferry. Here we first put foot on what was called the sacred soil of Virginia. Harper’s Ferry was historical ground. Here John Brown started an insurrection to liberate the slaves. Our march through the town was by way of Shenandoah Street, then by file left into a large open lot in town. Here we prepared our breakfast. Later we were allowed to visit the town and the points of interest. The old brick fire-engine house, known as John Brown’s Fort was one of the points of interest. Saw where the bricks had been knocked out for port-holes to fire through. A government arsenal had been located here. Destroyed by the rebels, only the old walls remained standing. Some severe fighting had taken place in this side hill town. At 5 P. M. we left the town on the march for Winchester. After a march of eight miles camped for the night in woods. Not being strong, after my illness, I was obliged to fall out by the roadside. Lieutenant Merwin wished me to return to the hospital. I answered no, I would rather die in the field, I wanted to stay with the boys. The Lieutenant was very kind to me, he taking my knapsack and the boys my equipment. After a short rest and a bath in a brook I was able to follow on, finding the regiment in camp for the night near Charlestown.

Saturday, 23d — We started this morning at daylight and marched five miles to General McPherson’s headquarters at the center of the army. Here we lay until 4 o’clock in the afternoon, when we marched back to our old place on the extreme left. The rebels again commenced to shell us, but the shells went over our heads. The Eleventh Iowa went on picket. Our men are shelling the rebels from all sides, and they are falling back behind their fortifications. When passing the headquarters of the Seventeenth Army Corps today, I saw a most dreadful sight at the field hospital ; there was a pile, all that a six-mule team could haul, of legs and arms thrown from the amputating tables in a shed nearby, where the wounded were being cared for.

May 23. — Rode along our picket line this morning, beginning near Mrs. Gray’s, and going from there to the extreme left. Saw nothing new. Day sultry and warm.

May 23 — I was at Dayton to-day and attended the funeral of a Maryland cavalryman who was buried by his comrades, with the honors of war. True, no sister’s tear-drop moistened his grave, yet the funeral rites were sanctified by the presence of woman, for many ladies of Dayton were at the burial, to pay their last sad respects to a departed defender.

May 23, Saturday. Met the President, Stanton, and Halleck at the War Department. Fox was with me. Neither Du Pont nor General Hunter has answered the President’s dispatch to them a month since. Halleck does not favor an attack on Charleston unless by the Navy. The army will second, so far as it can. Fox, who commanded the first military expedition to Sumter, is for a renewed attack, and wants the Navy to take the brunt. Stanton wants the matter prosecuted. I have very little confidence in success under the present admiral. It is evident that Du Pont is against doing anything, — that he is demoralizing others, and doing no good in that direction. If anything is to be done, we must have a new commander. Du Pont has talents and capability, but we are to have the benefit of neither at Charleston. The old army infirmity of this war, dilatory action, affects Du Pont. Commendation and encouragement, instead of stimulating him, have raised the mountain of difficulty higher daily. He is nursing Du Pont, whose fame he fears may suffer, and has sought sympathy by imparting his fears and doubts to his subordinates, until all are impressed with his apprehensions. The capture of Charleston by such a chief is an impossibility, whatever may be accomplished by another. This being the case, I have doubts of renewing the attack immediately, notwithstanding the zeal of Stanton and Fox. I certainly would not without some change of officers.

Having no faith, the commander can accomplish no work. In the struggle of war, there must sometimes be risks to accomplish results, but it is clear we can expect no great risks from Du Pont at Charleston. The difficulties increase daily [as] his imagination dwells on the subject. Under any circumstances we shall be likely to have trouble with him. He has remarkable address, is courtly, the head of a formidable clique, the most formidable in the Navy, loves intrigue, is jesuitical, and I have reason to believe is not always frank and sincere. It was finally concluded to delay proceedings until the arrival of General Gilmore, who should be put in possession of our views.

Sumner brought me this P.M. a report in manuscript of the case of the Peterhoff mail. I have read it and notice that the attorney, Delafield Smith, takes the opportunity to say, I doubt not at whose suggestion, that there is no report that the public mails have ever been opened and examined. He does not say there is any report they were not, or that there is any report whatever on the subject. All letters and papers deemed necessary are always examined. Upton well said in reply to Smith that the question had never been raised. Much time was spent in arguing this point respecting the mails. It was reported to Seward, and that point was seized upon, and the question raised, which led the President to call on me for a record of a case where public mails had been searched. Seward’s man, Delafield Smith, having learned through Archibald, the British Consul, that the Secretary of State had given up our undoubted right to search the mails, set up the pettifogging pretense that there was no report that captured mails ever had been examined, which Judge Betts did not regard, and Upton correctly said the point had never been raised. The court never asked permission of the Executive to try a prize case; there is no report that they ever asked or did not ask; the right was no more questioned than the right to search the mails.

23rd. Drew rations for the 7th Ohio. Got rations over for the remainder of the month. Potatoes and beans. Thede went out a mile or so with the horses and came back used up. Looks miserable. Eyes glaring and face emaciated. Made me frightened. Had the doctor look at him. Gave some rhubarb, uneasy during the night, cramps. Slept with him. Wrote to Fannie.

MAY 23D.—Our regiment lay in the rifle pits to-day, watching the enemy. For hours we were unable to see the motion of a man or beast on their side, all was so exceedingly quiet throughout the day. After dark we were relieved, and as we returned to the camp the enemy got range of us, and for a few minutes their bullets flew about us quite freely. However, we bent our heads as low as we could and double-quicked to quarters. One shot flew very close to my head, and I could distinctly recognize the familiar zip and whiz of quite a number of others at a safer distance. The rebels seemed to fire without any definite direction. If our sharpshooters were not on the alert, the rebels could peep over their works and take good aim; but as they were so closely watched they had to be content with random shooting.

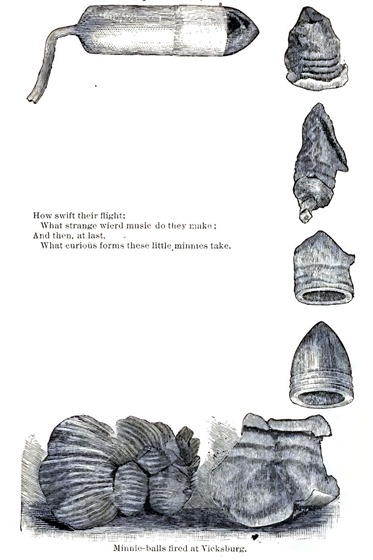

If this siege is to last a month there will be a whole army of trained sharpshooters, for the practice we are getting is making us skilled marksmen. I have gathered quite a collection of balls, which I mean to send home as relics of the siege. They are in a variety of shapes, and were a thousand brought together there could not be found two alike. I have picked up some that fell at my feet—others were taken from trees. I am the only known collector of such souvenirs, and have many odd and rare specimens. Rebel bullets are very common about here now—too much so to be valuable; and as a general thing the boys are quite willing to let them lie where they drop. I think, however, should I survive, I would like to look at them again in after years.

If this siege is to last a month there will be a whole army of trained sharpshooters, for the practice we are getting is making us skilled marksmen. I have gathered quite a collection of balls, which I mean to send home as relics of the siege. They are in a variety of shapes, and were a thousand brought together there could not be found two alike. I have picked up some that fell at my feet—others were taken from trees. I am the only known collector of such souvenirs, and have many odd and rare specimens. Rebel bullets are very common about here now—too much so to be valuable; and as a general thing the boys are quite willing to let them lie where they drop. I think, however, should I survive, I would like to look at them again in after years.

Shovel and pick are more in use to-day, which seems to be a sign that digging is to take the place of charging at the enemy. We think Grant’s head is level, anyhow. The weather is getting hotter, and I fear sickness; and water is growing scarce, which is very annoying. If we can but keep well, the future has no fears for us.

Saturday, 23rd—Went down to Finche’s and got a horse. Mr. Finch came out with us some distance. Came back to Norris; staid all night; nothing to eat.

May 23—Marched fifteen miles and halted. On our to-day’s march we saw any amount of dead horses, which did not smell altogether like cologne.