MAY 24TH.—Sunday; and how little like the Sabbath day it seems. Cannon are still sending their messengers of death into the enemy’s lines, as on week days, and the minnie balls sing the same song, while the shovel throws up as much dirt as on any other day. What a relief it would be if, by common consent, both armies should cease firing to-day. It is our regiment’s turn to watch at the front, so before daylight we moved up and took our position. We placed our muskets across the rifle pits, pointing towards the fort, and then lay down and ran our eyes over the gun, with finger on trigger, ready to fire at anything we might see moving. For hours not a movement was seen,  till finally an old half-starved mule meandered too close to our lines, when off went a hundred or more muskets, and down fell the poor mule. This little incident, for a few minutes, broke the monotony. A coat and hat were elevated on a stick above our rifle pits, and in an instant they were riddled with bullets from the enemy. The rebels were a little excited at the ruse, and probably thought, after their firing, there must be one less Yankee in our camp. In their eagerness a few of them raised their heads a little above their breastworks, when a hundred bullets flew at them from our side. They all dropped instantly, and we could not tell whether they were hit or not. The rebels, as well as ourselves, occasionally hold up a hat by way of diversion. A shell from an enemy’s gun dropped into our camp rather unexpectedly, and bursted near a group, wounding several, but only slightly, though the doctor thinks one of the wounded will not be able to sit down comfortably for a few days. I suppose, then, he can go on picket, or walk around and enjoy the country.

till finally an old half-starved mule meandered too close to our lines, when off went a hundred or more muskets, and down fell the poor mule. This little incident, for a few minutes, broke the monotony. A coat and hat were elevated on a stick above our rifle pits, and in an instant they were riddled with bullets from the enemy. The rebels were a little excited at the ruse, and probably thought, after their firing, there must be one less Yankee in our camp. In their eagerness a few of them raised their heads a little above their breastworks, when a hundred bullets flew at them from our side. They all dropped instantly, and we could not tell whether they were hit or not. The rebels, as well as ourselves, occasionally hold up a hat by way of diversion. A shell from an enemy’s gun dropped into our camp rather unexpectedly, and bursted near a group, wounding several, but only slightly, though the doctor thinks one of the wounded will not be able to sit down comfortably for a few days. I suppose, then, he can go on picket, or walk around and enjoy the country.

Friday, May 24, 2013

Sunday, 24th—To-night went down near Redman’s; run into Yankee pickets, and started back. Came cross railroad and out to Sherwin’s, got breakfast and on to Boss Meadows. From there to Hughe’s Shop; got two shoes and nails made. Went down to Essick’s and got supper and on top Mountain and staid all night.

24th May (Sunday).—We reached Meridian at 7.30 A.M., with sound limbs, and only five hours late.

We left for Mobile at 9 A.M., and arrived there at 7.15 P.M. This part of the line was in very good order.

We were delayed a short time owing to a “difficulty” which had occurred in the up-train. The difficulty was this. The engineer had shot a passenger, and then unhitched his engine, cut the telegraph, and bolted up the line, leaving his train planted on a single track. He had allowed our train to pass by shunting himself, until we had done so without any suspicion. The news of this occurrence caused really hardly any excitement amongst my fellow-travellers; but I heard one man remark, that “it was mighty mean to leave a train to be run into like that.” We avoided this catastrophe by singular good fortune.[1]

The universal practice of carrying arms in the South is undoubtedly the cause of occasional loss of life, and is much to be regretted; but, on the other hand, this custom renders altercations and quarrels of very rare occurrence, for people are naturally careful what they say when a bullet may be the probable reply.

By the intercession of Captain Brown, I was allowed to travel in the ladies’ car. It was cleaner and more convenient, barring the squalling of the numerous children, who were terrified into good behaviour by threats from their negro nurses of being given to the Yankees.

I put up at the principal hotel at Mobile—viz., the “Battlehouse.” The living appeared to be very good by comparison, and cost $8 a-day. In consequence of the fabulous value of boots, they must not be left outside the door of one’s room, from danger of annexation by a needy and unscrupulous warrior.

[1] I cut this out of a Mobile paper two days after:— “attempt To Commit Murder.—We learn that while the uptrain on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad was near Beaver Meadow, one of the employees, named Thomas Fitzgerald, went into one of the passenger cars and shot Lieutenant H. A. Knowles with a pistol, the ball entering his left shoulder, going out at the back of his neck, making a very dangerous wound. Fitzgerald then uncoupled the locomotive from the train and started off. When a few miles above Beaver Meadows he stopped and cut the telegraph wires, and then proceeded up the road. When near Lauderdale station he came in collision with the down-train, smashing the engine, and doing considerable damage to several of the cars.2 It is thought he there took to the woods; at any rate he has made good his escape so far, as nothing of him has yet been heard. The shooting, as we are informed, was that of revenge. It will be remembered that a few months ago Knowles and a brother of Thomas Fitzgerald, named Jack, had a renconter at Enterprise about a lady, and during which Knowles killed Jack Fitzgerald; afterwards it is stated that Thomas threatened to revenge the death of his brother; so on Sunday morning Knowles was on the train, as stated, going up to Enterprise to stand his trial. Thomas learning that he was on the train, hunted him up and shot him. Knowles, we learn, is now lying in a very critical condition.”

2 This is a mistake

Mo. Heights, May 24, 1863.

Dear Friends:

Yours found us all well. Was sorry to hear that Aunt D. was so near her end; but hers has been a life of sickness. We might say her last moments on earth would be the happiest she ever enjoyed for years. But to change the topic to the great cry of the nation, when is the war to be settled? I must say the matters look pretty blue. We must gain a victory soon, in some quarter and a great victory at that. If the papers speak the truth, the feelings of the people North are a little disloyal; I don’t mean in Mass., but more particularly the “Empire State,” especially on the Vallandigham case. He is a traitor and why not give him his dues? I see that he was not to be sent to Fort Warren but through our lines to the south. I hope Gov. Seymour will soon follow him; he certainly does no good to our cause, but on the contrary a great deal of harm. The weather has been very hot, but if there is a breeze we get it. It is beginning to get hard on us again, to have to go half way down the mountain for water, and if we don’t have rain soon, shall have to go to the foot. It is not very pleasant crawling up the mountain with a few canteens and a scorching sun sending its burning rays on to the back. Lieut. H. has returned to Co. H for duty; while here he won the enthusiasm of the men; if the men did not know the drill, he would take hold and show them and not damn them. The feelings of the Co. are worse than they have ever been before. I have no doubt if they had a leader to carry out any thing, some change might take place in the Company. There are fears that Harper’s Ferry will be attacked. The rebs have shown themselves rather plucky lately. I wish you would send me out my spanish book; we are having a small class in the barracks I stop in. Have got one man that can speak well. I have some one ask me every day how you are and if I think you will come out here this summer. What do you think of it? I remain, Your obt. servant,

L. B., Jr.

May 24—Laid here all day, it being Sunday.

Before Vicksburg, Sunday, May 24. Up and ready as ordered, but with the sun we unharnessed, watered and fed, then lay quiet all day. Washed and changed clothes, and Oh! what a relief. Truly water is a boon. Grant seems to be willing to allow the inhabitants of Vicksburg the Sunday for devotion. There has been but very little fighting to-day, little artillery firing. 4th Division passed in from Haynes Bluff for Warrenton.

Received a good mail which gladdened all our hearts. Oh! blessed white-winged messenger, how my mind has been occupied all day by sweet thoughts and hopes inspired by thy visits! Letters up to the 10th. Wrote a short and hurried letter home. Learned through the State Journal that a friend and former teacher, E. C. Hungerford, had fallen in the fight on the Rappahannock. It is another severe blow to his brother Tommy. How many, many more will this cruel war require to satisfy its victims. Wounded passing all day in ambulances to the river. Sergt. J. B. Jackson and L. N. Keeler gone. Sick.

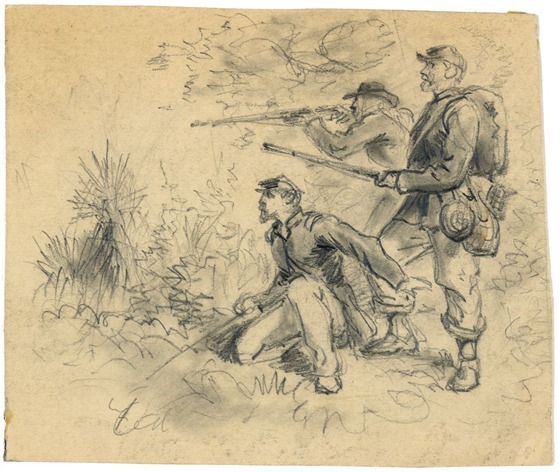

Drawing by Alfred R. Waud; no date given; drawing on cream paper : pencil ; 10.2 x 12.2 cm. (sheet); Library of Congress image.

__________

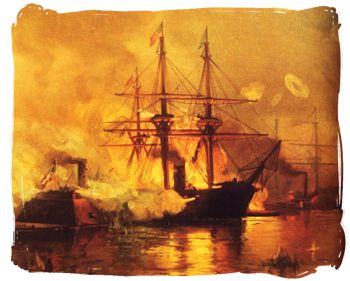

Note: This image has been digitally adjusted for fade correction, color, contrast, and saturation enhancement and selected spot removal.

Note: This image has been digitally adjusted for fade correction, color, contrast, and saturation enhancement and selected spot removal.

May 24th. Commences with pleasant weather. Light winds from S. E. Transports in sight coming down the river, and cavalry and infantry landing at the levee at Bayou Sara from four to eight A. M.; at eight thirty A. M. hove up anchor, got under way and steamed down the river; at nine thirty A. M. rounded to above Port Hudson, and fired a shell from the Sawyer rifle on poop, into the rebel batteries, to let them know we had come down to see them once more; at nine forty A. M. came to anchor five miles above Port Hudson. Received from the Albatross five rebel prisoners, hard looking fellows, on board, and kindly cared for them. These unfortunates were captured on a point of land opposite the rebel Gibraltar No. 2 of the Mississippi; at ten thirty A. M. called all hands to muster and performed Divine service. Heavy firing going on at Port Hudson. Received some more rebel prisoners this morning from the Albatross; they proved to be an officer and two privates belonging to a signal corps, they having been captured the day before by some of our pickets. Heavy firing heard in rear of Port Hudson. The mortar schooners below, engaged the rebel batteries also, from two thirty until four P. M. From four to six P. M., heavy cannonading between lower fleet and rebel batteries at Port Hudson, during this watch; also our army in rear of Port Hudson, engaged with the enemy; at six P. M. inspected crew at quarters. Received a mail on board from below.

May 24 — Sharp shooting and cannonading as usual this morning — continued all day —

We do not need geniuses; we have had enough of brilliant generals; and give us in the due course of promotion an honest, faithful, common-sensed and hard-fighting soldier, not stupid, and we feel sure of success.

Charles Francis Adams, Jr., to his father

Potomac Creek Bridge, Va.

May 24, 1863

Yours and Henry’s of May 1st with the accompanying volumes of Cust reached me last evening. One of your May letters is still missing. The volumes of Cust are most acceptable. They are written with more spirit than I should expect in so old a man, and his military characters of leading Generals are really in their way admirable — pen and ink sketches of the best class. It is really a most useful book for me and a most admirable selection. If I remain long a soldier it will be of no small use in my education. Did I thank you for “The Golden Treasury “? It’s strange. I laughed as I opened it, it seemed such an odd book for a camp and the field; but strangely enough I find that I read it more than any book I have, and that it is more eagerly picked up by my friends. It is very pleasant to lie down in all this dust and heat and to read some charming little thing of Suckling’s and Herrick’s.

I laughed heartily over your and Henry’s accounts of Earl Russell’s diplomacy and the John Bull diplomacy. How strange, and he a man who will figure in history. John Bull backed you right down and made you explain and eat your humble pie, and every one admired his bold position and laughed at your humiliation; and then comes the secret history and Bottom, that roaring lion, becomes Bottom the sucking dove, and winks at the alarmed Plenipotentiary and says, “it is only I, Bottom the joiner.” And so after all, that high toned descendant of all the Bedfords is no better than some men we do not admire nearer home. But I cannot but wonder at Russell’s course. Any day may force him into real collision with you; the danger of this is imminent; and if it comes, what a terrible handle he has given you… You could expose him to two continents, and your silence now would make the exposure more galling. It seems to me that the noble Earl is now under heavy bonds for his good behavior for the remainder of your term. I think the last part of that term is going to be far more pleasant than the first.

I am very hopeful and sanguine, though no longer confident. In spite of a wretched policy in Washington which perpetually divides and dissipates our strength; and in spite of the acknowledged mediocrity of our Generals, our sheer strength is carrying through this war. In this Army of the Potomac affairs are today truly deplorable, and yet I lose and the army loses no heart — all underneath is so sound and good. We know, we feel, that our misfortunes are accidents and that we must work through them and the real excellence which we daily see and feel must come to the surface. The truth in regard to the late battles is gradually creeping out, and the whole army — Cavalry, Artillery, Infantry and Engineers — feel and know that they won the one decided victory of the war and that Hooker threw it away. Hooker today, I think, stands lower in the estimation of the army than ever did the redoubtable John Pope; but what can we do? Sickles, Butterfield and Hooker are the disgrace and bane of this army; they are our three humbugs, intriguers and demagogues. Let them be disposed of and the army would be well satisfied to be led by any of the corps commanders. We do not need geniuses; we have had enough of brilliant generals; and give us in the due course of promotion an honest, faithful, common-sensed and hard-fighting soldier, not stupid, and we feel sure of success. There are plenty to choose from — Sedgwick, Meade, Reynolds, Slocum and Stoneman, any of them would satisfy. I do not dare to discuss our western prospects. If Vicksburg falls, I care very little what becomes of Richmond, and Grant seems to be doing well. I am sanguine but not as confident, for I cannot forget how McClellan was within four miles of Richmond when the reinforcements of the enemy poured in. Grant must be quick, for if we do not soon hear of the capture of Vicksburg, or of some point necessitating its final fall, I fear we shall hear a different and older story. However, let us hope for the best and fight it out.

Since I last wrote a week ago, nothing of moment has turned. We are still in this hot, exposed, dusty and carrion-scented camp and, as sure as fate will all be sick unless we move out of this region of poisoned atmosphere. We are under orders for early tomorrow morning and I do hope we shall get away. Anything is better, and already all the impetus of my four weeks campaign has expended itself.

We have been going through a course of cleanliness and inspection, getting the men and arms clean and neat, and bringing up our discipline. In hot weather this is very charming and when accompanied by the miserable slavery which is one of the traditions of discipline in this regiment, it makes a camp life of monotony, varied by ham and hard bread (literally my only fare for weeks past) in itself not attractive, as adventitiously disagreeable as may be. On the 9th of April last I had permission to leave camp and dined at General Devens’. On the 17th of May, after four weeks of field duty and not one hour of the whole six weeks off duty, I asked permission of Colonel Curtis to ride over to dine with an old friend at General Sedgwick’s, it being a Sunday afternoon. After much hemming and hawing I was point-blank refused on some miserable reason, such as that I was the only officer in my company here, or something of that sort. With old schoolmates and acquaintances within sight by the dozen, Paul Revere, Sam Quincy and such as they, I have never seen one of them and, for all the good they do me, they might as well be with you. Of course such a system as this, while it does stop gadding on the part of officers, does not tend to make life pleasant or one’s duties agreeable, and, proverbially timid as I am, I think I would rather fight three battles a week and be in the field, than thus rot and rust in camp. Curtis is a good officer and a better fellow and as strict in his own duty as in ours; but while I decidedly admire his faculty of saying “no” to his most intimate associates here, it certainly does not serve to make our pork and hard-bread more palatable. So here I am, attending daily to the needs of my men and horses, duly seeing that hair is short and clothes are clean, paying great attention to belts and sabres, inspecting pistols and policing quarters and so, not very intellectually and indeed with some sense of fatigue, playing my part in the struggle. . . .

The papers have just come with the news of Grant’s successes. This, if all be true, settles in our favor the material issue of the war, and, in a military point of view, I do not see how it can fail, with the recognized energy of our western Generals, to make the destruction of the confederacy as a military power a mere question of time. Our raids would seem to show that the Confederates have no reserve strength. If this be so, their line is like a chain the strength of which is equal to the strength of the weakest link. Broken at Vicksburg they must fall in Tennessee and can be forced out of Virginia. We shall see. Meanwhile let me congratulate you. The fall of Vicksburg will not tend, I imagine, to aggravate your diplomatic troubles.