Wednesday 3rd—Ordered to remain in Camp.

Monday, June 3, 2013

June 3. — James came to me this morning, and said that he wished to go home. I shall have to let him go, I am afraid. Captain Dalton was over here this afternoon, and took dinner with us. Late at night we received orders to be ready to march at daylight in the morning. Day pleasant and cool. Showers in the morning and evening. General Reynolds returned from Washington this evening. Had a letter from Hannah saying that I was commissioned a captain in the 18th.1[1]

[1] My commission was dated May 4, 1863.

Wednesday, 3d—We lay still again today, but all improved their time cleaning up their accouterments. We drew two days’ rations, which relieved our hunger. We received orders to march early in the morning. Colonel Chambers returned from the North today. He is to take command of our brigade, a thing a great many of the boys were sorry to learn.

JUNE 3D.—Expected to move to-day, but got orders instead to remain in camp. Have heard heavy cannonading towards Vicksburg. Would prefer to take our place in the line around the city rather than stay away, for there is glory in action. It may be very nice, occasionally, to rest in camp, but to hear firing and to snuff the battle afar off, creates a natural uneasiness. Besides, if the city should surrender in the meantime, we might be cheated out of our share in a prize, to the taking of which we have contributed some valuable assistance.

Newsboys are thick in camp, with the familiar cries, “Chicago Times” and “Cincinnati Commercial.” The papers sell quite freely. At home each man wants to buy a paper for himself, but here a single copy does for a whole company, and the one that buys it reads it aloud—a plan which suits the buyer very well, if not the seller. While some of these papers applaud the bravery of the generals and their commands, and pray that the brilliancy of past achievements be not dimmed by dissensions in the face of the enemy, other papers have articles that sound to us like treason, slandering the soldier and denouncing the government. But they can not discourage or demoralize this army, for it was never stronger or more determined than now, and it will continue to strike for our country, even though bleeding at every pore. The rebels can not be subdued, so they say. Why not? In two years have we not penetrated to the very center of the South? And in less than that time we shall be seen coming out, covered all over with victory, from the other side.

Newsboys are thick in camp, with the familiar cries, “Chicago Times” and “Cincinnati Commercial.” The papers sell quite freely. At home each man wants to buy a paper for himself, but here a single copy does for a whole company, and the one that buys it reads it aloud—a plan which suits the buyer very well, if not the seller. While some of these papers applaud the bravery of the generals and their commands, and pray that the brilliancy of past achievements be not dimmed by dissensions in the face of the enemy, other papers have articles that sound to us like treason, slandering the soldier and denouncing the government. But they can not discourage or demoralize this army, for it was never stronger or more determined than now, and it will continue to strike for our country, even though bleeding at every pore. The rebels can not be subdued, so they say. Why not? In two years have we not penetrated to the very center of the South? And in less than that time we shall be seen coming out, covered all over with victory, from the other side.

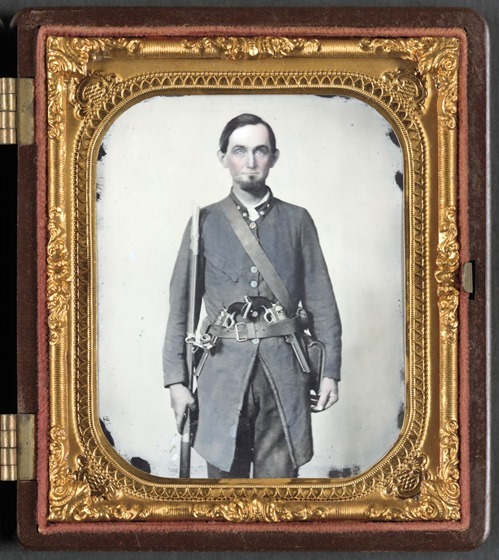

Private Jackson A. Davis of Co. E, Holcombe Legion South Carolina Cavalry Battalion, with musket and two pistols.

sixth-plate ambrotype, hand-colored ; 9.5 x 8.4 cm (case)

Donated by Tom Liljenquist; 2012

Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs; Ambrotype/Tintype photograph filing series; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Record page for image is here.

__________

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

- fade correction,

- color, contrast, and/or saturation enhancement

- selected spot removal.

Civil War Portrait 037

Colonel Lyons.

Fort Donelson, June 3, 1863.—Colonel Lowe was telegraphed for on account of the sickness of his wife, and the command of the post will doubtless be on my shoulders for some weeks. There is no danger at present that we shall be sent away from here. I do not like to have this responsibility upon me at all, but must stand it, I reckon. Captain Ruger starts out in the morning to make his surveys, or rather to commence them. His wife will worry for fear he will be shot by guerillas. When you write to her tell her that I will keep a strong guard of cavalry and infantry with him, and will do everything possible for his safety that I can.

June 3 — Rained last night, which made the red yellow clay in these Tuckeyhoe roads almost as sticky as shoemaker’s wax. We renewed our march this morning. Early in the day we passed Wolftown, a little hamlet of some six houses. Yesterday we crossed Middle and South Ann, and to-day we crossed North Ann, insignificant little streamlets that come down from the Blue Ridge. Their confluence forms the Rapidan. We passed through Madison Court House to-day. The town is situated on a wave-like swell, considerably elevated above the surrounding country. The houses are comparatively small, and most, or nearly all of them, are built of wood. The town in general is on the scattered order.

This afternoon we passed through a very small nest of a village sporting the great big name of James City. It is situated in a rolled-up country in the western part of Culpeper County. We crossed Robinson River today in Madison County. We are camped this evening at Bethel Church, nine miles from Culpeper Court House.

June 3.—Col. Kilpatrick returned from an expedition through the country situated between the Rappahannock and York Rivers, in Virginia, having been entirely successful.—(Doc. 3.)

—A meeting was held at Sheffield, England, under the presidency of Mr. Alderman Saunders, at which the following resolution was adopted:

“That this meeting has heard with profound regret of the death of Lieutenant-General Thomas Jefferson Jackson, of the confederate States of North-America; a man of pure and upright mind, devoted as a citizen to his duty, cool and brave as a soldier, able and energetic as a leader, of whom his opponents say he was ‘sincere and true and valiant.’ This meeting resolves to transmit to his widow its deep and sincere condolence with her in her grief at the sad bereavement, and with the great and irreparable loss the army of the confederate States of America have sustained by the death of their gallant comrade and general.” It was decided to request Mr. Mason to transmit the resolution to Mrs. Jackson and the troops lately commanded by the deceased General. —Ashepoo, S. C., was destroyed by the National forces, under the command of Colonel Montgomery, of the Second South-Carolina colored volunteers.—(Doc. 55.)

—Admiral Du Pont ordered Lieutenant Commander Bacon to proceed with the Commodore McDonough on an expedition against Bluffton, on the May River, S. C., a stream emptying into the Calibogue.

The army forces were landed near Bluffton, by the gunboat Mayflower and an army transport, under the protection of the Commodore McDonough, and took possession of the town, the rebels having retreated. By the order of Colonel Barton, the town was destroyed by fire, the church only being spared; and though the rebel troops made several charges, they were driven back by the troops, and the shells and shrapnel of the Commodore McDonough. Bluffton being destroyed, the soldiers reembarked without casualties, and returned to Hilton Head.—(Doc. 54.)

June 3, Wednesday. Wrote Du Pont that Foote would relieve him. I think he anticipates it and perhaps wants it to take place. He makes no suggestions, gives no advice, presents no opinion, says he will obey orders. He is evidently uneasy, — it appears to me as much dissatisfied with himself as any one. Everything shows he is a disappointed man, afflicted with his own infirmities. I perceive he is preparing for a controversy with the Department, —laying out the ground, getting his officers committed, —and he has besides strong friends in Congress and elsewhere. He has been well and kindly treated by the Department. I have the name and blame of favoring him by some of the best officers, and have borne with his aberrations passively.

The arrest of Vallandigham and the order to suppress the circulation of the Chicago Times in his military district issued by General Burnside have created much feeling. It should not be otherwise. The proceedings were arbitrary and injudicious. It gives bad men the right of questions, an advantage of which they avail themselves. Good men, who wish to support the Administration, find it difficult to defend these acts. They are Burnside’s, unprompted, I think, by any member of the Administration and yet the responsibility is here unless they are disavowed and B. called to an account, which cannot be done. The President — and I think every member of the Cabinet—regrets what has been done, but as to the measures which should now be taken there are probably differences.

The constitutional rights of the parties injured are undoubtedly infringed upon. It is claimed, however, that the Constitution, laws, and authorities are assailed with a view to their destruction by the Rebels, with whom V. and the Chicago Times are in sympathy and concert. The efforts of the Rebels are directed to the overthrow of the government, and V. and his associates unite with them in waging war against the constituted authorities. Should the government, and those who are called to legally administer it, be sustained, or should those who are striving to destroy both? There are many important and difficult problems to solve, growing out of the present condition of affairs. Where is the constitutional right to interdict trade between citizens, to blockade the ports, to seize private property, to dispossess and occupy the houses of the inhabitants, etc., etc.? In peaceful times there would be no right to do these things; it may be said there would be no necessity. Unfortunately the peaceful operations of the Constitution have been interrupted, obstructed, and are still obstructed. A state of war exists; violent and forcible measures are resorted to in order to resist and destroy the government, which have begotten violent and forcible measures to vindicate and restore its peaceful operation. Vallandigham and the Chicago Times claim all the benefits, guarantees, and protection of the government which they are assisting the Rebels to destroy. Without the courage and manliness to go over to the public enemy, to whom they give, so far as they dare, aid and comfort, they remain here to promote discontent and disaffection.

While I have no sympathy for those who are, in their hearts, as unprincipled traitors as Jefferson Davis, I lament that our military officers should, without absolute necessity, disregard those great principles on which our government and institutions rest.

3d June (Wednesday). — Bishop Elliott left for Savannah at 6 A.M., in a downpour of rain, which continued nearly all day. Grenfell came to see me this morning in a towering rage. He had been arrested in his bed by the civil power on a charge of horse-stealing, and conniving at the escape of a negro from his master. General Bragg himself had stood bail for him, but Grenfell was naturally furious at the indignity. But, even according to his own account, he seems to have acted indiscreetly in the affair of the negro, and he will have to appear before the civil court next October. General Polk and his officers were all much vexed at the occurrence, which, however, is an extraordinary and convincing proof that the military had not superseded the civil power in the Southern States; for here was an important officer arrested, in spite of the commander-in-chief, when in the execution of his office before the enemy. By standing bail, General Bragg gave a most positive proof that he exonerated Grenfell from any malpractices.[1]

In the evening, after dark, General Polk drew my attention to the manner in which the signal beacons were worked. One light was stationary on the ground, whilst another was moved backwards and forwards over it. They gave us intelligence that General Hardee had pushed the enemy to within five miles of Murfreesborough, after heavy skirmishing all day.

I got out of General Polk the story of his celebrated adventure with the —— Indiana (Northern) regiment, which resulted in the almost total destruction of that corps. I had often during my travels heard officers and soldiers talking of this extraordinary feat of the “Bishop’s.” The modest yet graphic manner in which General Polk related this wonderful instance of coolness and bravery was extremely interesting, and I now repeat it, as nearly as I can, in his own words.

“Well, sir, it was at the battle of Perryville, late in the evening—in fact, it was almost dark when Liddell’s Brigade came into action. Shortly after its arrival I observed a body of men, whom I believed to be Confederates, standing at an angle to this brigade, and firing obliquely at the newly arrived troops. I said, ‘Dear me, this is very sad, and must be stopped;’ so I turned round, but could find none of my young men, who were absent on different messages; so I determined to ride myself and settle the matter. Having cantered up to the colonel of the regiment which was firing, I asked him in angry tones what he meant by shooting his own friends, and I desired him to cease doing so at once. He answered with surprise, ‘I don’t think there can be any mistake about it; I am sure they are the enemy.’ ‘Enemy!’ I said; ‘why, I have only just left them myself. Cease firing, sir; what is your name, sir?’ ‘My name is Colonel ——, of the ——Indiana; and pray, sir, who are you?’

“Then for the first time I saw, to my astonishment, that he was a Yankee, and that I was in rear of a regiment of Yankees. Well, I saw that there was no hope but to brazen it out; my dark blouse and the increasing obscurity befriended me, so I approached quite close to him and shook my fist in his face, saying, ‘I’ll soon show you who I am, sir; cease firing, sir, at once.’ I then turned my horse and cantered slowly down the line, shouting in an authoritative manner to the Yankees to cease firing; at the same time I experienced a disagreeable sensation, like screwing up my back, and calculating how many bullets would be between my shoulders every moment. I was afraid to increase my pace until I got to a small copse, when I put the spurs in and galloped back to my men. I immediately went up to the nearest colonel, and said to him, ‘Colonel, I have reconnoitred those fellows pretty closely—and I find there is no mistake who they are; you may get up and go at them.’ And I assure you, sir, that the slaughter of that Indiana regiment was the greatest I have ever seen in the war.”[3]

It is evident to me that a certain degree of jealous feeling exists between the Tennesseean and Virginian armies. This one claims to have had harder fighting than the Virginian army, and to have been opposed to the best troops and best generals of the North.

The Southerners generally appear to estimate highest the north-western Federal troops, which compose in a great degree the armies of Grant and Rosecrans; they come from the states of Ohio, Iowa, Indiana, &c. The Irish Federals are also respected for their fighting qualities; whilst the genuine Yankees and Germans (Dutch) are not much esteemed.

I have been agreeably disappointed in the climate of Tennessee, which appears quite temperate to what I had expected.

[1] I cut this out of a Charleston paper some days after I had parted from Colonel Grenfell: Colonel Grenfell was only obeying General Bragg’s orders in depriving the soldier of his horse, and temporarily of his money:—

“Colonel St Leger Grenfell.—The Western army correspondent of the ‘Mobile Register’ writes as follows :—The famous Colonel St Leger Grenfell, who served with Morgan last summer, and since that time has been Assistant Inspector-General of General Bragg, was arrested a few days since by the civil authorities. The sheriff and his officers called upon the bold Englishman before he had arisen in the morning, and after the latter had performed his toilet duties he buckled on his belt and trusty pistols. The officer of the law remonstrated, and the Englisher damned, and a struggle of half an hour ensued, in which the stout Britisher made a powerful resistance, but, by overpowering force, was at last placed hors de combat and disarmed.[2] The charges were, that he retained in his possession the slave of a Confederate citizen, and refused to deliver him or her up; that meeting a soldier coming to the army leading a horse, he accused him of being a deserter, dismounted him, took his horses and equipments and money, stating that deserters were not worthy to have either horses or money, and sent the owner thereof off where he would not be heard of again. The result of the affair was, that Colonel Grenfell, whether guilty or not guilty, delivered up the negro, horses, and money to the civil authorities. If the charges against him are proven true, then there is no doubt that the course of General Bragg will be to dismiss him from his staff; but if, on the contrary, malicious slanders are defaming this ally, he is Hercules enough and brave enough to punish them. His bravery and gallantry were conspicuous throughout the Kentucky campaign, and it is hoped that this late tarnish on his fame will be removed; or if it be not, that he will.”

[2] This is all nonsense—the myrmidons of the law took very good care to pounce upon Colonel Grenfell when he was in bed and asleep.

[3] If these lines should ever meet the eyes of General Polk, I hope he will forgive me if I have made any error in recording his adventure.