June 9 — We had another grand military display to-day, of a very distinctly different kind from those of a few days ago, however, but not far from the same field. This time the Yanks played a very conspicuous part in it, and there were no friendly charges in it nor sham battle business with blank cartridges, but plenty of bullets, bloody sabers, and screaming shell. West Pointers may know all about the theoretical probabilities and concomitant intricacies of war, but I think that for the last few nights the horse artillery has been permitted to roost a little too near the lion’s lair. As an evidence of that fact, early this morning the Yankees gathered in all the household and kitchen furniture, as well as some of the personal effects, belonging to our major, and came very near capturing some of the horse artillerymen in bed.

Our camp last night was in the edge of a woods, and this morning at daylight, just as we were rounding up the last sweet snooze for the night, bullets fresh from Yankee sharpshooters came from the depths of the woods and zipped across our blanket beds, and then such a getting up of horse artillerymen I never saw before. Blankets were fluttering and being rolled up in double-quick time in every direction, and in less than twenty minutes we were ready to man our guns, and all our effects safely on the way to the rear. Before I got out of bed I saw a twig clipped from a bush by a Yankee bullet not more than two feet above my head.

Captain Hart’s South Carolina battery was camped on the right of the battalion and near the Beverly Ford road, and some of his men rushed from their beds to their guns and drew by hand one of their pieces to the road and opened fire down the road and on the woods from where the bullets came. Their timely and considerate act alone checked for a little while the enemy’s precipitate advance, and peradventure if it had not been for that precious little check some of us horse artillerymen would be on the weary road this evening to some of Uncle Sam’s elegant hotels specially devised for the royal entertainment of Southern Rebels.

All of the foregoing events occurred before sunrise and before any of our cavalry appeared on the field in the immediate vicinity of our camp, but soon after Captain Hart’s gun opened fire our cavalry began to arrive in double-quick time, and some of them with drawn sabers ready for business.

Just as we moved out of camp a portion of Jones’ brigade of cavalry came rushing on the field and advanced with drawn sabers on the woods we had just left, which were swarming with the enemy’s horsemen. We moved at a quick gallop march out into the open field, and about four hundred yards from the woods we wheeled our guns in battery on a little rising ground and prepared for immediate action. One of Beckham’s batteries was there in position already and another wheeled in battery immediately after we did, all in close proximity and in line on the same wave-like swell of rising ground.

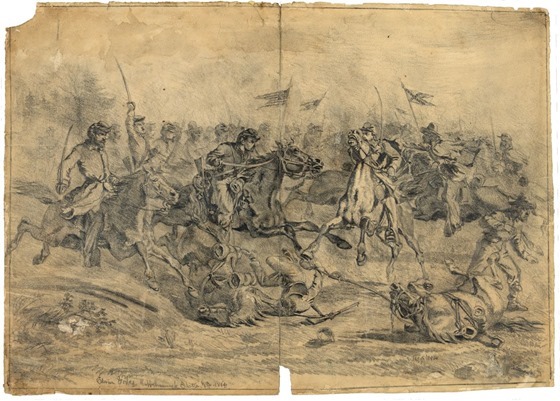

While we were getting ready for action our cavalry advanced to the edge of the woods, but had to retire immediately, as the woods were full of Yankee horsemen and dismounted sharpshooters. Soon after our cavalry fell back into the field the Yankee cavalry made a charge from the woods into the open field. Our courageous cavalry gallantly withstood the enemy’s first determined charge, and the field in front of the woods was covered with a mingled mass, fighting and struggling with pistol and saber like maddened savages.

At that juncture of the fray the warlike scene was fascinatingly grand beyond description, and such as can be produced and acted only by an actual and real combat. Hundreds of glittering sabers instantly leaped from their scabbards, gleamed and flashed in the morning sun, then clashed with metallic ring, searching for human blood, while hundreds of little puffs of white smoke gracefully rose through the balmy June air from discharging firearms all over the field in front of our batteries.

During the first charge in the early morn the artillerymen stood in silent awe gazing on the struggling mass in our immediate front, yet every man was at his post and ready for action at a moment’s notice; and as soon as our cavalry repulsed the enemy and drove them back into the woods, sixteen pieces of our horse artillery opened fire on the woods with a crash and sullen roar that made the morning air tremble and filled the woods with howling shell. Then for a while the deep diapason roar of artillery mixed with sharp crash of small arms swept over the trembling field and sounded along the neighboring hills like a rumbling chariot of rolling thunder.

We kept up a steady artillery fire for awhile, until the enemy in our front disappeared from sight and retired deeper into the woods; then we ceased firing, but held our position some three or four hours.

The fields where the first fray of the day occurred are low and nearly level, and the enemy as yet had no artillery on the field, but from apparent indications they were seeking for suitable positions for batteries on our immediate right flank, consequently we retired from our first position to obviate a direct enfilade fire and also to obtain and occupy higher ground.

As we were falling back General William E. Jones, commander of Ashby’s old brigade, but from some cause not in command to-day, passed us and made the following remarks as he was riding along: “Captain Chew, I am not in command to-day, but do you see that gap in the woods yonder. I think the Yankees are bringing a battery there; if they do, give them hell.”

We moved back until we were nearly a mile from the gap in the woods to which General Jones directed our attention. We were still on low ground, but we halted, and I was ordered to put my gun into position, load and be ready to open fire as soon as the Yankee battery appeared in the little opening in the woods. The Yankees were a little slow, and I suppose very cautious in making their appearance in the little opening with their battery, and in the meantime our first lieutenant rode away to another portion of the field for the purpose of finding a better and more commanding position for our guns. While he was away the Yankee battery appeared in the gap and immediately wheeled in battery in double-quick time and opened fire on us. We then had no orders to fire, yet my gun was loaded, aimed, and ranged, and ready to fire. I was so anxious to open fire on the battery and try to accomplish that which General Jones told us to do,— to drive the battery away or silence it,— that my eagerness almost impelled me to dash away the barrier imposed by rigid army regulations which strictly forbid a gunner to fire without orders from a higher officer.

After the Yankee battery fired two shell at us we received orders to limber up and advance, but before we limbered up I asked the orderly sergeant to permit me to fire my gun before we advanced, but he replied that we had no orders to fire. I told him that my gun was loaded with a percussion shrapnel shell, and that it would be dangerous to move the gun any distance, as the shell might churn out at any moment on a move, explode, and hurt some of our mess.

He then told me that if I fired I would have to do it on my own responsibility and assume the consequences, all of which I was willing to do. Then I gave the command to fire. The next moment my faithful twelve-pound shell was whizzing through the air, speeding toward the enemy’s position, where their guns were still thundering. My shell struck one of the guns in the Yankee battery and disabled it. The remainder of the battery abandoned the position, and we heard no more thunder of Yankee guns from the gap in the woods during the remainder of the day. We then advanced to a new position, but soon after we arrived there the enemy’s cannon began to roar at Brandy Station, right square in our rear, and the cavalry in our immediate front instantly grew bolder and pressed us harder. The fire of the sharpshooters, with their long-ranged rifles, grew fiercer every moment, and for awhile the gloom of disaster and defeat hung like a smothering pall over the prospects of victory.

BRANDY STATION

When the first inauspicious boom of cannon rolled over the fields from our rear and fell on the responsive ears of Ashby’s old veterans, it was like an electric shock which first stuns, then reanimates, and in less time than it takes to relate it our cavalry was rushing toward the enemy in our rear, in regular charging speed, with nerves and courage strung to the highest pitch — every man determined to do or die. We followed close after them with the battery at a double-quick gallop.

The dust in the road was about three inches deep, and in our hurried movement my mule fell down and rolled over me, and I over him, both of us wallowing in three inches of dust, and for once I and my mule favored and looked alike so far as color was concerned. By the time I got my mule up and I was mounted again the battery had disappeared in a thick cloud of flying dust.

The body of Yankee cavalry — General Gregg’s division — that appeared in our rear crossed the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford about seven miles below Beverly Ford, and moved up on this side of the river, striking the Orange and Alexandria Railroad at Brandy Station, then advanced-in our rear.

Nearly a mile from Brandy Station and in the direction of Beverly Ford is Fleetwood Heights, a prominent hill jutting boldly out from the highland on the west to an almost level plain on the east and south.

The enemy in our rear had already gained the heights and were strongly posted on the crest, with a line of cavalry and a battery of artillery not far away ready to open fire, when our cavalry arrived in sight of the formidable hill that was crowned with threatening danger and almost ready to burst into battle.

There was not a moment to lose if our cavalry expected to gain the heights from the enemy’s grasp and possession, and hold them, and it had to be done instantly and by a hand-to-hand and hill-to-hill conflict. The decision for a saber charge was consummated in a moment, and our cavalry gallantly dashed up the slope of Fleetwood, with gleaming sabers, and charged the formidable line of cavalry that had opened a terrific fire from the crest of the hill. Then commenced the hand-to-hand conflict which raged desperately for awhile, the men on both sides fighting and grappling like demons, and at first it was doubtful as to who would succumb and first cry enough; but eventually the enemy began to falter and give way under the terrible strokes of the Virginian style of sabering. Yet the enemy fought stubbornly and clung tenaciously to their position. They rallied twice after their line was broken the first time, and heroically renewed the struggle for the mastery of the heights, but in their last desperate effort to regain and hold their position our cavalry met the onset with such cool bravery and rigid determination that the enemy’s overthrow and discomfiture was so complete that they were driven from the hill, leaving three pieces of their artillery in position near the crest of the heights and their dead and wounded in our hands. When we arrived with our battery on top of Fleetwood the Yanks had already been driven from the hill and were retreating across the plain toward the southeast. Squadrons and regiments of horsemen were charging and fighting on various parts of the plain, and the whole surrounding country was full of fighting cavalrymen. Away to the southeast General Hampton had his South Carolinians in splendid battle line, with drawn sabers ready to charge the retiring foe. Clouds of dust mingled with the smoke of discharging firearms rose from various parts of the field, and the discordant and fearful music of battle floated on the thickened air. Several times during the day the battle-field presented a scenic view that the loftiest thought of my mind is far too low and insignificant to delineate, describe, or portray. The charmed dignity of danger that evinces and proclaims its awe-inspiring presence by zipping bullets, whizzing shell, and gleaming sabers lifted the contemplation of the tragical display from the common domain of grandeur to the eloquent heights of sublimity.

Stirring incidents and exciting events followed one another in quick succession, and no sooner was the enemy dislodged in our rear, than a heavy force that had been fighting us all morning advanced on our front, with cavalry and artillery. Their batteries at once opened a severe fire on our position, to which we immediately replied. Then the hardest and liveliest part of the artillery fighting commenced in earnest, and the thunder of the guns roared fiercely and incessantly for several hours.

At one time the Yankee gunners had such perfect range and distance of our position that their shrapnel shell exploded right over our guns, and two or three times I heard the slugs from the exploding shell strike my gun like a shower of iron hail. One shell exploded fearfully close to me and seriously wounded two of my cannoneers and raked the sod all around me. For about three long hours whizzing shot, howling shell, exploding shrapnel, and screaming fragments filled the air that hung over Fleetwood Heights with the music of war. After a severe cannonading for several hours the fire of the Yankee battery slackened, and soon after ceased altogether, and the battery abandoned their position and withdrew their guns beyond the range of our fire. Just before the Yankee battery ceased firing a large body of Yankee cavalry moved in solid column out in the open field about a mile and a half from our position. They remained there about two hours in a solid square, for the purpose, we supposed, of making a desperate charge on the hill and our battery, if their battery would have succeeded in partially silencing our guns.

After the enemy’s battery ceased firing Captain Chew ordered me to get ready to fire canister, and if the Yankee cavalry attempted to charge us I must reserve my fire until they charged to within three hundred yards of my gun, then open fire with canister, carefully aim at the horses’ knees and fire as rapidly as possible. But after threateningly menacing our position for about two hours, the immense host of Yankee horsemen in our immediate front withdrew from the field, disappeared in a woods, and I saw them no more, for soon afterwards the battle ended, and the enemy retreated and recrossed the river. Several times during the day I saw General Stuart, when the battle raged the fiercest, dash with his staff across the field, passing from point to point along his line, perfectly heedless of the surrounding danger.

The Yanks cruelly rushed us out of camp this morning before breakfast, consequently we had nothing to eat during the whole day until after dark this evening, and strange to say I did not experience any hunger until after the battle was over. If the empty stomach telegraphed to the brain for rations during the battle the brain was so intensely engaged in something of far more importance than responding to an empty stomach that it heedlessly disregarded the signal and carefully concealed the cravings of hunger until it could be satisfied at a more convenient season.

We were on the field twelve hours, and during that time I fired my faithful gun one hundred and sixty times. This evening just before the battle closed, with the last few shots we fired I saw the fire flash from the cascabel of my gun, and I found that it was disabled forever — burnt entirely out at the breach. After my gun was disabled I was ordered to retire it from the field immediately, and I moved it back to our wagons near Culpeper Court House, and camped for the night.

A little while before the battle ended some of General Early’s division of infantry of Ewell’s corps came up and formed in line just in rear of our battery, but the enemy fell back and gave up the field soon afterwards, and General Early’s infantry marched back toward Culpeper Court House.

The enemy’s forces we fought to-day were under the command of General Pleasanton. He had three divisions of cavalry, with a complement of artillery — six batteries, I think — the whole backed by two brigades of infantry. His forces recrossed the river this evening and General Stuart held the battle-field.