12th June (Friday).—I called at an exchange office this morning, and asked the value of gold: they offered me six to one for it. I went to a slave auction at 11; but they had been so quick about it that the whole affair was over before I arrived, although I was only ten minutes late. The negroes—about fifteen men, three women, and three children—were seated on benches, looking perfectly contented and indifferent I saw the buyers opening the mouths and showing the teeth of their new purchases to their friends in a very business-like manner. This was certainly not a very agreeable spectacle to an Englishman, and I know that many Southerners participate in the same feeling; for I have often been told by people that they had never seen a negro sold by auction, and never wished to do so. It is impossible to mention names in connection with such a subject, but I am perfectly aware that many influential men in the South feel humiliated and annoyed with several of the incidents connected with slavery; and I think that if the Confederate States were left alone, the system would be much modified and amended, although complete emancipation cannot be expected; for the Southerners believe it to be as impracticable to cultivate cotton on a large scale in the South, without forced black labour, as the British have found it to produce sugar in Jamaica; and they declare that the example the English have set them of sudden emancipation in that island is by no means encouraging. They say that that magnificent colony, formerly so wealthy and prosperous, is now nearly valueless—the land going out of cultivation—the Whites ruined—the Blacks idle, slothful, and supposed to be in a great measure relapsing into their primitive barbarism.

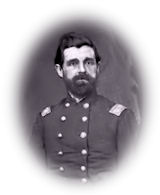

At 12 o’clock I called by appointment on Captain Tucker, on board the Chicora.[1] The accommodation below is good, considering the nature and peculiar shape of the vessel; but in hot weather the quarters are very close and unhealthy, for which reason she is moored alongside a wharf on which her crew live.

Captain Tucker expressed great confidence in his vessel during calm weather, and when not exposed to a plunging fire. He said he should not hesitate to attack even the present blockading squadron, if it were not for certain reasons which he explained to me.

Captain Tucker expects great results from certain newly-invented submarine inventions, which he thinks are sure to succeed. He told me that, in the April attack, these two gunboats were placed in rear of Fort Sumter, and if, as was anticipated, the Monitors had managed to force their way past Sumter, they would have been received from different directions by the powerful battery Bee on Sullivan’s Island, by this island, Forts Pinckney and Ripley, by the two gunboats, and by Fort Johnson on James Island—a nest of hornets from which they would perhaps never have returned.

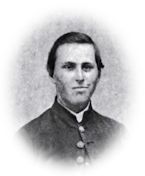

At 1 P.M. I called on General Beauregard, who is a man of middle height, about forty-seven years of age. He would be very youthful in appearance were it not for the colour of his hair, which is much greyer than his earlier photographs represent. Some persons account for the sudden manner in which his hair turned grey by allusions to his cares and anxieties during the last two years; but the real and less romantic reason is to be found in the rigidity of the Yankee blockade, which interrupts the arrival of articles of toilette. He has a long straight nose, handsome brown eyes, and a dark mustache without whiskers, and his manners are extremely polite. He is a New Orleans Creole, and French is his native language.

He was extremely civil to me, and arranged that I should see some of the land fortifications to-morrow. He spoke to me of the inevitable necessity, sooner or later, of a war between the Northern States and Great Britain; and he remarked that, if England would join the South at once, the Southern armies, relieved of the present blockade and enormous Yankee pressure, would be able to march right into the Northern States, and, by occupying their principal cities, would give the Yankees so much employment that they would be unable to spare many men for Canada. He acknowledged that in Mississippi General Grant had displayed uncommon vigour, and met with considerable success, considering that he was a man of no great military capacity. He said that Johnston was certainly acting slowly and with much caution; but then he had not the veteran troops of Bragg or Lee. He told me that he (Beauregard) had organised both the Virginian and Tennessean armies. Both are composed of the same materials, both have seen much service, though, on the whole, the first had been the most severely tried. He said that in the Confederate organisation a brigade is composed of four regiments, a division ought to number 10,000 men, and a corps d’armée 40,000. But I know that neither Polk nor Hardee have got anything like that number.[2]

At 5.30 P.M. the firing on Morris Island became distinctly audible. Captain Mitchell had evidently commenced his operations against Little Polly.

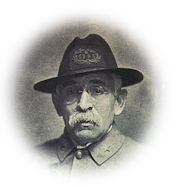

Whilst I was walking on the battery this evening, a gentleman came up to me and recalled himself to my recollection as Mr Meyers of the Sumter, whom I had known at Gibraltar a year ago. This was one of the two persons who were arrested at Tangier by the acting United States consul in such an outrageous manner. He told me that he had been kept in irons during his whole voyage, in the merchant vessel, to the United States; and, in spite of the total illegality of his capture on neutral ground, he was imprisoned for four months in Fort Warren, and not released until regularly exchanged as a prisoner of war. Mr Meyers was now most anxious to rejoin Captain Semmes, or some other rover.

I understand that when the attack took place in April, the garrison of Fort Sumter received the Monitors with great courtesy as they steamed up. The three flagstaffs were dressed with flags, the band from the top of the fort played the national airs, and a salute of twenty-one guns was fired, after which the entertainment provided was of a more solid description.

[1] I have omitted a description of this little gunboat, as she is still doing good service in Charleston harbour—November 1863.

[2] A division does nearly always number 10,000 men, but then there are generally only two or three divisions in a corps d’ armée.