Charles Francis Adams, Jr., to his father

June 14, 1863 (continuation of

letter started June 8)

We saddled in haste and I was ordered to take my company down at once towards Sulphur Springs, gathering up our discomforted pickets as I went along, until I met the enemy, when I was to engage him and retreat on our reserve as slowly as possible. I must say I thought that this was ramming me in as I had less than fifty men; but off I started bound to do my best, though I must say I felt a little relieved when Major Higginson came up and joined me and I felt not wholly alone. For my only other officer at the time was Pat Jackson, a boy of eighteen and only a few weeks out from home — worse than nothing. Within half a mile we met the company which had been engaged, pretty well used up — both officers gone and a number of men; the rest flushed and hatless from their rapid retreat, but all steady and quiet under the command of Sergeant Jimmy Hart, an old rough and fighting man, and evidently there was lots of fight in them yet. They reported the enemy variously from 1000 to 1800 strong and in pursuit, but somehow they had n’t seen them for the last few miles. They fell in in my rear and we pushed forward. Of course we expected a shindy and, as usual, when expected it did n’t come. Every instant I expected to run onto the enemy’s advanced guard or picket, and ordered my advance the instant they caught sight of a vidette to drop their carbines and dash at him with their sabres; but none came in sight and finally we came out on the hill over the ford and hotel and, behold! the enemy was gone and the coast was clear. So we re-established the line and got back to the reserve in time to find the brigade under arms and out to support us.

On the whole it might have been improved but it was a good thing. It was a repetition of my experience last February at Hartwood Church on men of different stuff from the 16th Pennsylvania. The enemy, came down some 600 strong to capture our picket force at Sulphur Springs. There we had thirty-three men under two officers posted with their nearest support two miles off, and that only ten men, and the reserve ten miles off. The enemy threw some three hundred men, as the negroes told us, across the river and came up to rout and capture our party. Lieutenant Gleason, who commanded, with more spirit than discretion, at once went in for a fight, though he believed there were at least 800 of them. Accordingly the rebs found a wolf where they looked for a hare. For as they came up the hill to the woods where Gleason lay he rammed his thirty men into the head of their column, knocking them clean off their legs and down the hill. So far was excellent and now, with his prisoners and booty, he should have at once arranged for a slow, ugly retreat, and the rebs would not have been anxious to hurry him too much. But no, he was there, he seemed to think, to fight and so presently the rebs came up and at them he went once more, and then of course, it was all up with him and the road was open to the enemy clean back to us. He staggered them again, but they rallied — a sabre cut over the head brought him off his horse, the other officer got separated from his men — they fell into confusion, and after that they retreated, without order but still showing fight. The enemy, astonished at the fierceness of the resistance, followed but a short distance and then fell back across the river. They took one prisoner, a Sergeant who was dismounted, but was captured fighting like a devil with his back to a tree. Gleason escaped through the woods and came in with a handsome sabre cut and otherwise no loss; while, as we the next day discovered, they carried home quite a collection of lovely gashes.

I did not get back into camp until after eight o’clock and it was ten before we got settled and quiet. Next day a force came out to relieve us and we would have gone in had they not come out so late. As it was we waited till next day, resting our horses and ourselves and then on Friday the fifth we marched leisurely to the Brigade camp. We got into camp at one o’clock, expecting a little chance now to rest and refit, but that evening we were ordered to be ready to march at seven o’clock and march we did, though not far. They got us out and in column at nine P.M. and at ten sent us back with orders to be ready at two A.M., and so, having effectually spoilt our night, at two A.M. they had us up and at half past three we were on the march. The whole division marched down to Sulphur Springs and just at noon our regiment was pushed across the river and sent on to Jefferson, for no purpose that I then could or now can see but to pick a fight. We went to Jefferson and looked round but saw no enemy, and presently they sent us on to Hazel River and I was ordered to take my squadron down to the river and “stir up the enemy’s pickets.” I did so, but the enemy’s pickets when they saw me coming put boots and declined to be stirred, so I returned, capturing on my way home a secesh officer, whose horse I spied outside of a house in which, all unconscious of danger, he was getting something to eat. So towards evening we fell back on the road to the Springs.

We got there and crossed just at sunset, dirty, hungry, tired, and with weary and unfed horses. We did hope that here they would put us into camp; but with an hour’s delay for feeding our horses, we were mounted again and marched clean back into camp, nearly twenty miles. It was an awful march and I never saw such drowsiness in a column before. Men went sound asleep in the saddle and their horses carried them off. It was laughable. I repeatedly lost the column before me while asleep and two of my four chiefs of platoons marched rapidly by me on their way to the head of the column, sound asleep and bolt upright. We reached camp at three A.M. of Sunday, having been gone just twenty-four hours, with twenty-two of them in the saddle. For once the next day reveille was omitted by common consent and all hands slept until nine o’clock. We were pretty tired and looked jaded and languid. I certainly felt so, and could not muster the energy to write a letter.

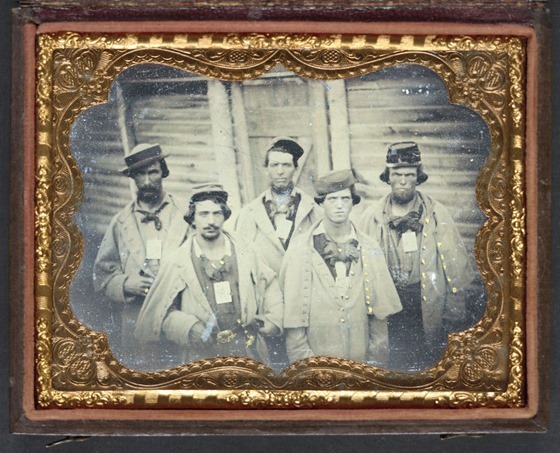

Monday the eighth we set to work to repair damages. Our horses were thin and poor, they needed shoes, our baggage needed overhauling and reduction. We all need new clothes, for we are curiously ragged and dirty and my clothes are waiting for me in Washington, but I cannot get them forward. How astonished you would be to see me in my present “uniform.” My blue trousers are ragged from contact with the saddle and so covered with grease and dust that they would fry well. From frequent washing my flannel shirts are so shrunk about the throat that they utterly refuse to button and, so perforce, “I follow Freedom with my bosom bare.” I wear a loose government blouse, like my men’s, and my waistcoat, once dark blue, is now a dusty brown. I have no gloves and those boots of the photograph, long innocent of blacking, hang together by doubtful threads. These, with hair cropped close to my head, a beard white with dust and such a dirty face, constitute my usual apparel. Read this to Browning and ask him to write a poem on the real horrors of war.

In this condition last Monday we thought to take advantage of a day’s quiet to start afresh, and in this hope we abided even until noon, when orders came for us to immediately prepare to move with all our effects. This was an awful blow to me, for I knew it would cost me my poor dog “Mac.” He had followed me through thick and thin so far, but three days before he was taken curiously ill with a sort of dropsical swelling and now was so bad that he could not follow me. When we moved I got him into an ambulance in which Gleason was carried to Warrenton Junction, but there was no one to take care of him, and I traced him down to Bealeton next day, following one of our officers, and there he disappeared. Poor Mac! I felt badly enough. He was very fond of me and I of him and it made me feel blue to reflect that all his friskings of delight when I came round were over and that he would sleep under my blanket no more. However, in campaigning we risk and lose more than the company of animals, and I could not let this loss weigh on me too heavily.

Our column got in motion at about five o’clock and we marched to Morrisville. What with various delays it was eleven o’clock before we got into camp and then we had had nothing to eat. At last this was forthcoming, such as it was. It was well past twelve before we got down to sleep and I for one was just dozing off —had not lost consciousness — when reveille was somewhere sounded. “That’s too horrid;” I thought, “it must be some other division.” But at once other bugles caught it up in the woods around and, just as they, began the first started off on “The Assembly” and the others chased after it through that and the breakfast call, until the woods rang and the division awoke under the most amazing snarl of simultaneous calls from Reveille to “Boots and Saddle” that ever astonished troopers. But we shook ourselves and saddled our horses, and at two o’clock we were on the road. Heaven only knows where they marched us, but one thing was clear — after five hours hard marching we had only made as many miles and reached Kelly’s Ford. We crossed at once and began to take our share in the fight of Tuesday, 9th.

I have n’t time or paper to describe what we saw of that action, nor would my story be very interesting. We were not very actively engaged or under heavy fire and our loss did not exceed ten or a dozen. In my squadron one man was wounded; but the work was very hard, for we penetrated clean to the enemy’s right and rear at Stevensburg and about noon were recalled to assist General Gregg, and from two A.M. to two P.M. the order to dismount was not once given. The day was clear, hot and intensely dusty; the cannonading lively and the movements, I thought, slow. I am sure a good cavalry officer would have whipped Stuart out of his boots; but Pleasonton is not and never will be that. In addition to the usual sights of a battle I saw but one striking object — the body of a dead rebel by the road-side the attitude of which was wonderful. Tall, slim and athletic, with regular sharply chiseled features, he had fallen flat on his back, with one hand upraised as if striking, and with his long light hair flung back in heavy waves from his forehead. It was curious, no one seems to have passed that body without the same thought of admiration. . . .