June 21.—At Baltimore, Md., as a matter of precaution against rebel demonstrations, earthworks were erected around the north and west sides of the city. The Council appropriated a forge sum of money, and a very large force of laborers (mostly contrabands) were impressed into the service. A line of barricades, composed of tobacco hogsheads and empty sugar and molasses hogsheads, filled with brick and sand, was erected within the city, extending from the high ground on the east to the south-western extremity. “These, if the rebels should come,” said a participant, “will be defended by the Union League men, who are being armed by General Schenck, and should a cavalry force manage to dash past the batteries, they would here meet a formidable resistance. The Union men are entirely confident that should the rebels be so rash as to attempt a raid in this direction, they will be able to effectually defeat them.”

—The Aeronautic corps of the army of the Potomac was dispensed with, and the balloons and inflating apparatus were sent to Washington.

—The fight at Lafourche Crossing, La., was renewed this day, and ended in the defeat of the rebels with a loss of sixty killed, two hundred and forty wounded, and seventy prisoners. The Union loss was eight killed and sixteen wounded.—New-Orleans Era, Jane 23.

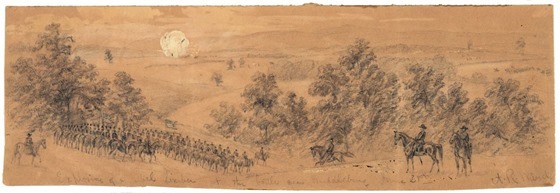

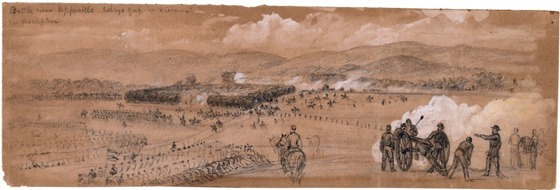

—Major-General Pleasanton, with his cavalry, attacked the rebels, under General Stuart, at Middleburgh, Va., and after driving them over eight miles, succeeded in capturing two pieces of artillery, and sixty prisoners, besides killing and wounding over one hundred men.—(Doc. 77.)

—The ship Byzantium and bark Goodspeed were captured and burned by the rebel privateer Tacony off the coast of Massachusetts.—On the approach of the rebels toward Shippensburgh, Pa., the proprietor of the Union Hotel in that town blurred his sign over with brown paint.— The steamer Victory was captured off Cuba by the gunboat Santiago de Cuba, and the English schooner Frolic off Crystal Run, Florida, by the gunboat Sagamore.—This afternoon a party of the First Maryland cavalry, under Major Cole, dashed into Frederick, Md., driving out the rebels and capturing one. On the retirement of the Nationals, however, the rebels returned and reoccupied the town.