December 10th. Left camp early this morning. Passed through Martinsburg, going east, bound for Charlestown. Weather good. After a march of about eight miles, came to a halt at Leestown for rest and rations. Again on the march, forded the Opequan Creek. Not very pleasant at this time of year. Soldiers must not stop for wet feet. Pushing on. After a march of about eighteen miles we reached the town of Charlestown, Virginia, eight miles south of Harper’s Ferry, just after dark, tired. Took possession of an old church for our quarters, the weather growing colder. No place for a fire. Trying to make ourselves comfortable for the night.

December 2013

The Oaks, St. Helena, December 10,1863.

Dear Family All: — It is hard for me and for us all, I know, that this letter is all of me that comes by this steamer. I can’t bear to think of what you will say and how you will look when you get it. Don’t be very angry with me (as I think you must be at first), but consider that I am not disregarding all your requests by my free will, but by really cruel circumstances, and that I am bitterly disappointed myself.

I had made every arrangement to go with Rina and Captain Hooper, and was making plans day and night for getting to you and thinking of nothing but the pleasure we should have. But since Miss Ruggles’ death I never dared to dwell with too much certainty upon our meeting at any set time, and it fairly made me tremble to see by your letters how much you were all setting your minds upon it. Though Ellen was still very ill when I wrote last, we had good hopes that she would be well enough for me to leave her by Xmas, and, from General Saxton down to the negro boys in the yard, everybody was helping forward my going. But on the twenty-eighth day of the sickness, the quinine seemed to have lost its effect, or there was some unfavorable circumstance which brought on a relapse. I sent for Dr. Rogers. He thought she must have the wisest medical aid or there was little hope for her. I told him that she had no home at the North and was unwilling to go with me without, or even with, invitation from my friends. Then he said, “You must stay with her; she will die if you leave her.” I asked whether he thought it would be long before I could go, and he said hers must be a tedious convalescence — that the responsibility and risk of taking her North made it better for me not to urge her going, but that he must warn me not to go away till she was in a different state from now. So I have made up my mind to it, and I do not dare to think of Xmas at all. I hope she will get well sooner than he thinks, for she has gone on famously for the last four or five days. I shall set out as soon as she is well enough to go to her mother and do without medicine. Meanwhile I turn Kitty’s ring and say, “Patience! Patience!” . . .

General Saxton received Mr. Furness’ letter and came directly over to see me and order me home, but he went away convinced that there was but one thing to be done. Those who have been of the household know well enough that I did not want any order from General Saxton nor urging from Mr. Furness to take me to home and Christmas, but all agree that there is only one way for me now, and that is to put off going till I can do so without leaving Ellen so ill.

December 11, Friday.

There are some other reasons besides Ellen’s sickness which make it better for me to be here, though I should not have let them detain me. One is the sale of the furniture. I want to buy a cheap table, a chair, a bedstead; or, if I can, I want to claim these things as necessary to me as a teacher. If I am here I may get them granted to me, but if I am away, there is nothing to be done but to buy them when I come back, and I may not be able to do it. Then if the places are leased by January 1st, as is expected, the resident teachers will be able to claim a home, but there would be a small chance for absentees. Ellen will not be at “The Oaks,” nor well enough to attend to my interests. Still, though I should like to keep this home, I would not stop a day to do it, for there would surely be some place for me near the school. A little while ago Mr. Phillips spoke in a way that seemed to threaten our school. He said the church building[1] belonged to private parties, and he interfered with our school arrangements. Colonel Higginson was here at the time and he afterwards spoke to General Saxton about it. General S. said we should be unmolested as long as he was in the department, for that he had rather a hundred such churches as Mr. Phillips’ should be closed than one such school as ours. Harriet is going to open it as soon as we get the stove up. I shall not teach again before I go home, I think. Ellen is not well enough to leave, and I shall rest here and make a business of it, since I cannot go home to rest with you all; though I do not really need any rest, but freedom from anxiety. I suppose the school would add a little to that, and so I shall not begin till I am easy in mind and eager for work once more. We have been having a good deal of company, but I am not housekeeper and don’t care. Colonel Higginson’s nephew is here now, sick, and being cared for by Mr. Tomlinson. He has just sent Ellen and me a half pillowcase full of beautiful Spitzenberg apples from a box he has just received. He occupies Mr. Tomlinson’s room with him. Mr. T. is the kindest of nurses to these sick young officers. He talks of going to Morris Island with good things for the soldiers there for Christmas.

Saturday evening.

It is storming so that I am afraid the ferry will not cross to-morrow morning, and then this letter may be too late for the steamer. This worries me dreadfully, for I am sure that you all will fret if you do not hear from me. I can hardly bear your disappointment, and I feel as if I cannot bear your anxiety on my account. You need not worry about my health. It keeps good and I shall take care of it, for I know how much it is worth. I shall be glad to escape anxiety, but that I could not do by going home now — it would be an incessant care and fear and self-reproach.

I should really fear to leave in such a storm, or after it, my recollection of the one I came through to get here being still vivid.

I have read over my letter and see that it seems cold and heartless and does not let you know at all how I am grieved about disappointing you, and at being separated on this day when we hoped our circle would be complete once more. But I am troubled enough about it, and do all I can not to think or feel too much till I get to you once more. I am in a hard trial on my account and on yours.

Good night! A happy Christmas to you all, and a bright New Year. You must be merry and make believe I am there.

We shall have no Christmas for the school and no school probably. I am so sorry for that. I cannot bear to stop, but must, and so good-night again, and best love to all from far away,

L.

[1] The brick church, in which Miss Towne and Miss Murray had opened their school.

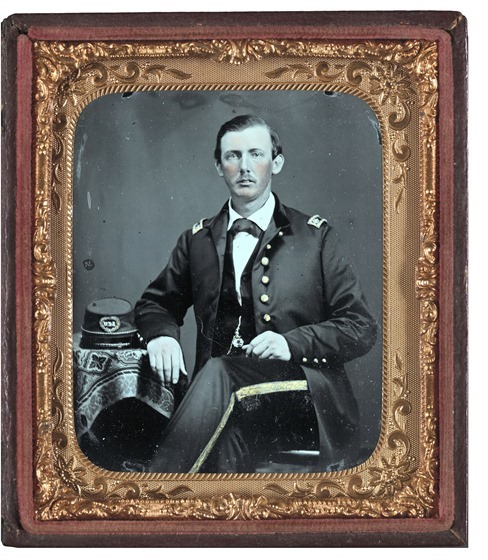

Captain James Dugan Gist of General & Staff Confederate States Infantry Regiment in uniform with South Carolina Volunteers kepi

Birth: Jun. 12, 1833

Death: Aug. 23, 1863 Mississippi

__________

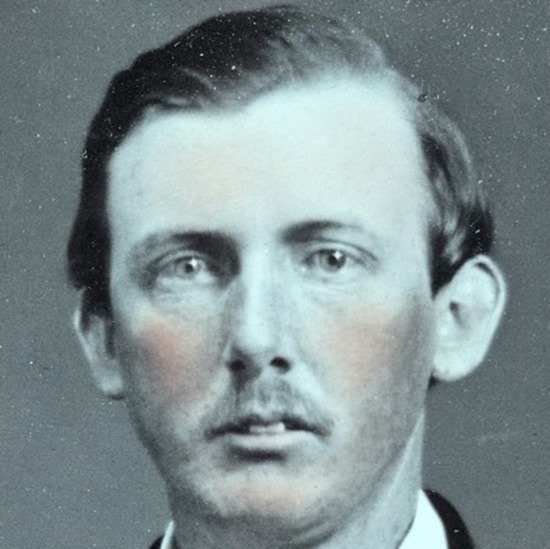

Close-up crop:

__________

Sixth-plate ambrotype, hand-colored ; 9.2 x 8.1 cm (case)

Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs; Ambrotype/Tintype photograph filing series; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Record page for image is here.

__________

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

- fade correction,

- color, contrast, and/or saturation enhancement

- selected spot and/or scratch removal

- cropped for composition and/or to accentuate subject matter

- straighten image

Civil War Portrait 100

by John Beauchamp Jones

DECEMBER 10th.—No news from any of the armies, except that Longstreet has reached Bristol, Va.

Yesterday, in Congress, Mr. Foote denounced the President as the author of all the calamities; and he arraigned Col. Northrop, the Commissary-General, as a monster, incompetent, etc.—and cited * * * *

I saw Gen. Bragg’s dispatch to-day, dated 29th ult., asking to be relieved, and acknowledging his defeat. He says he must still fall back, if the enemy presses vigorously. It is well the enemy did not know it, for at that moment Grant was falling back on Chattanooga! Mr. Memminger has sent to Congress an impracticable plan of remedying the currency difficulty.

To-day I saw copies of orders given a year ago by Gen. Pemberton to Col. Mariquy and others, to barter cotton with the enemy for certain army and other stores.

It is the opinion of many that the currency must go the way of the old Continental paper, the French assignats, etc., and that speedily.

Passports are again being issued in profusion to persons going to the United States. Judge Campbell, who has been absent some weeks, returned yesterday.

The following prices are quoted in to-day’s papers:

“The specie market has still an upward tendency. The brokers are now paying $18 for gold and selling it at $21; silver is bought at $14 and sold at $18.

“GRAIN.—Wheat may be quoted at $15 to $18 per bushel, according to quality. Corn is bringing from $14 to $15 per bushel.

“FLOUR.—Superfine, $100 to $105; Extra, $105 to $110.

“CORN-MEAL.—From $15 to $16 per bushel.

“COUNTRY PRODUCE AND VEGETABLES.—Bacon, hoground, $3 to $3.25 per pound; lard, $3.25 to $3.50; beef, 80 cents to $1; venison, $2 to $2.25; poultry, $1.25 to $1.50; butter, $4 to $4.50; apples, $65 to $80 per barrel; onions, $30 to $35 per bushel; Irish potatoes, $8 to $10 per bushel; sweet potatoes, $12 to $15, and scarce; turnips, $5 to $6 per bushel. These are the wholesale rates.

“GROCERIES.—Brown sugars firm at $3 to $3.25; clarified, $4.50; English crushed, $1.60 to $5; sorghum molasses, $13 to $14 per gallon; rice, 30 to 32 cents per pound; salt, 35 to 40 cents; black pepper, $8 to $10.

“LIQUORS.—Whisky, $55 to $75 per gallon; apple brandy, $45 to $50; rum, proof, $55; gin, $60; French brandy, $30 to $125; old Hennessy, $180; Scotch whisky, $90; champagne (extra), $350 per dozen ; claret (quarts), $90 to $100; gin, $150 per case; Alsop’s ale (quarts), $110; pints, $60.”

December 10.—Major-General Grant, from his headquarters at Chattanooga, Tenn., issued the following congratulatory order to his army: “The General commanding takes this opportunity of returning his sincere thanks and congratulations to the brave armies of the Cumberland, the Ohio, the Tennessee, and their comrades from the Potomac, for the recent splendid and decisive successes achieved over the enemy. In a short time you have recovered from him the control of the Tennessee River from Bridgeport to Knoxville. You dislodged him from his great stronghold upon Lookout Mountain, drove him from Chattanooga Valley, wrested from his determined grasp the possession of Missionary Ridge, repelled with heavy loss to him his repeated assaults upon Knoxville, forcing him to raise the siege there, driving him at all points, utterly routed and discomfited, beyond the limits of the State. By your noble heroism and determined courage, you have most effectually defeated the plans of the enemy for regaining the possession of the States of Kentucky and Tennessee. You have secured positions from which no rebellious power can drive or dislodge you. For all this the General commanding thanks you collectively and individually. The loyal people of the United States thank and bless you. Their hopes and prayers for your success against this unholy rebellion are with you daily. Their faith in you will not be in vain. Their hopes will not be blasted. Their prayers to Almighty God will be answered. You will yet go to other fields of strife; and with the invincible bravery and unflinching loyalty to justice and right, which have characterized you in the past, you will prove that no enemy can withstand you, and that no defences, however formidable, can check your onward march.”

—Genebal Gilmore again shelled Charleston, S. C, throwing a number of missiles into different parts of the city. The rebel batteries opened fire, and a heavy bombardment ensued for several hours.—The steamers Ticonderoga, Ella, and Annie, left Boston, Mass., in pursuit of the Chesapeake.—The new volunteer fund of New-York City reached seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars.

Thursday, 10th—We start for Longstreet for or via Sevier. Gave it out and started for the vicinity of Bess’ Mill. Went to see Mr. Jo Gray, a Lieut, in the Yankee Army. He was not at home; took two horses and a negro. Came on to McCully’s and got two of them, two guns and one pistol, two horses. Came on to Bess’ but found them all gone, then came back to Mr. Bright’s.

Bridgeport, Wednesday, Dee. 9. Rain ceased, sun appeared and the deep slushy mud soon dried up. After dinner I was detailed to help take horses to turn them over with Lieutenant Simpson. Took thirty-eight horses and three mules, crossed the bridge on to the island, and had to go up stream two miles to the corral. Its presence was manifested by the stench from far off from the carrion of the dead. They filled for acres the woods to a number almost incredible, starved to death. The corral-master was an old-looking man. We found him in an isolated clapboard house with only two or three inhabitants. He must enjoy the life of a hermit. The corral was a field of ten acres containing three thousand to four thousand head of mules and horses, all much pulled down for want of feed. It was sundown before we turned them over. Had three miles of bad road to camp. Walked it through the dark, lost our track several times. Found a good supper of fried beef and biscuit awaiting us. Spent evening in Griff’s tent listening to music of flute and vocal as discoursed by Byness, Parker, etc.

December 9th.—” Come here, Mrs. Chesnut,” said Mary Preston to-day, ” they are lifting General Hood out of his carriage, here, at your door.” Mrs. Grundy promptly had him borne into her drawing-room, which was on the first floor. Mary Preston and I ran down and greeted him as cheerfully and as cordially as if nothing had happened since we saw him standing before us a year ago. How he was waited upon! Some cut-up oranges were brought him. “How kind people are,” said he. “Not once since I was wounded have I ever been left without fruit, hard as it is to get now.” “The money value of friendship is easily counted now,” said some one, “oranges are five dollars apiece.”

9th. Up early and breakfasted on mush. Supper last night the same. Infantry soon commenced passing. Left all boys but Thede and went on. Passed through Rutledge. Command moved on to Bean Station and camped—some skirmishing. Issued Hard Bread and beef! Boys came up. Bunked down by the fire and slept soundly. Cold night. Boys go for secesh badly on this trip.

Wednesday, 9th.—Notified that a man would be shot Friday.