January 15.—Nothing new from the armies—all quiet. At home we are in statu quo, except that we have had a very agreeable accession to our family party in the person of Colonel C. F. M. G. He sleeps in his office, and messes with us. He cheers us every day by bringing the latest news, in the most pleasant form which the nature of the case will admit. My occupation at home just now is as new as that in the office—it is shoe-making. I am busy upon the second pair of gaiter boots. They are made of canvas, presented me by a friend. It was taken from one of our James River vessels, and has been often spread to the breeze, under the “Stars and Bars.” The vessel was sunk among the obstructions at Drury’s Bluff. The gaiters are cut out by a shoemaker, stitched and bound by the ladies, then soled by a shoemaker, for the moderate sum of fifty dollars. Last year he put soles on a pair for ten dollars. They are then blacked with the material used for blacking guns in the navy. They are very handsome gaiters, and bear polishing by blacking and the shoe-brush as well as morocco. They are lasting, and very cheap when compared with those we buy, which are from $125 to $150 per pair. We are certainly becoming very independent of foreign aid. The girls make beautifully, fitting gloves, of dark flannel, cloth, linen, and any other material we can command. We make very nice blacking, and a friend has just sent me a bottle of brilliant black ink, made of elderberries.

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

January 15th.—What a day the Kentuckians have had! Mrs. Webb gave them a breakfast; from there they proceeded en masse to General Lawton’s dinner, and then came straight here, all of which seems equal to one of Stonewall’s forced marches. General Lawton took me in to supper. In spite of his dinner he had misgivings. “My heart is heavy,” said he, “even here. All seems too light, too careless, for such terrible times. It seems out of place here in battle-scarred Richmond.” “I have heard something of that kind at home,” I replied. “Hope and fear are both gone, and it is distraction or death with us. I do not see how sadness and despondency would help us. If it would do any good, we would be sad enough.”

We laughed at General Hood. General Lawton thought him better fitted for gallantry on the battle-field than playing a lute in my lady’s chamber. When Miss Giles was electrifying the audience as the Fair Penitent, some one said: “Oh, that is so pretty!” Hood cried out with stern reproachfulness: “That is not pretty; it is elegant.”

Not only had my house been rifled for theatrical properties, but as the play went on they came for my black velvet cloak. When it was over, I thought I should never get away, my cloak was so hard to find. But it gave me an opportunity to witness many things behind the scenes—that cloak hunt did. Behind the scenes! I know a little what that means now.

General Jeb Stuart was at Mrs. Randolph’s in his cavalry jacket and high boots. He was devoted to Hetty Cary. Constance Cary said to me, pointing to his stars, “Hetty likes them that way, you know—gilt-edged and with stars.”

Friday, 15th—Camp and picket duty are becoming very light as compared to one month ago. Some of the regiments sent to Minnesota and western Iowa to drive back the Indians, are returning to camp. It is reported that the Sixteenth Army Corps will soon return from Chattanooga. We hear also that General Sherman will command an expedition from Vicksburg across the state to Meridian, Mississippi.

15th. On soon after daylight. Meal and coffee for breakfast. Raised a little blood. Hard work. Meat and salt. No prospect of boat. I am played out.

Huntsville, Friday, Jan. 15. Little rain last night and looks like more. Quite muddy and disagreeable. Another large mail received, among which was one for me from my aged father in his own handwriting and language; gave me much pleasure to peruse. Cousin Griffith quitted the officers’ mess this afternoon, and came in with us.

January 15, Friday. A little ill for a day or two. Edgar and the Miss F. s from Harrisburg left. At the Cabinet. Little done. Friends in Connecticut are some of them acting very inconsiderately. They feel outraged by the conduct of Dixon and others in procuring the nomination of Henry Hammond for marshal, a nomination eminently unfit to be made. The President was deceived into that matter. He was told that Hammond and the clique were his true supporters and friends, and that those opposed were his enemies. This falsehood the disappointed ones seem determined to verify by making themselves opponents.

January 15.—The weather has cleared off, and all seem glad of the change.

Mr. Bradley has had his arm amputated; he came here with a slight wound on his elbow, made by an ax. Gangrene got into it, and could not be arrested. It eat so rapidly that the joint was nearly destroyed.

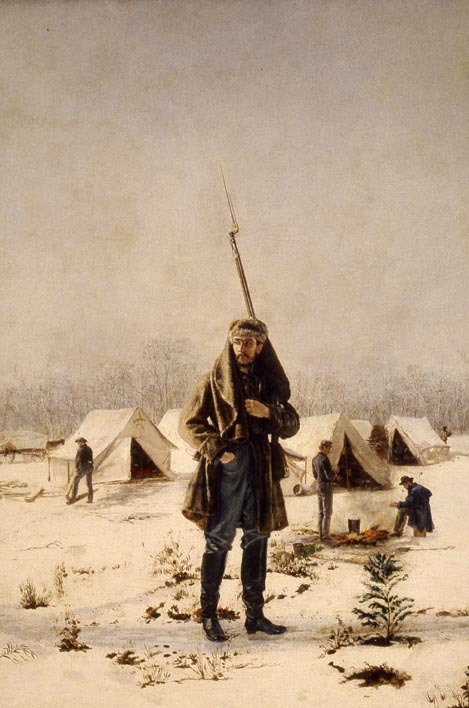

Painting by Conrad Wise Chapman, oil painting 1874; Confederate soldier, in fur hat, beard, brown winter coat, blue trousers and black boots holding a bayonet in his left arm, looks off to right; white snow-covered ground with few plants; in background are white tents, to right are two men with fire, to left is man chopping wood, beyond tents are barren trees and gray sky.

by John Beauchamp Jones

JANUARY 15TH.—We have no news. But there is a feverish anxiety in the city on the question of subsistence, and there is fear of an outbreak. Congress is in secret session on the subject of the currency, and the new Conscription bill. The press generally is opposed to calling out all men of fighting age, which they say would interfere with the freedom of the press, and would be unconstitutional.

January 15.—The United States schooner Beauregard captured, near Mosquito Inlet, the British schooner Minnie, of and from Nassau.

—”The utmost nerve,” said the Richmond Whig, “the firmest front, the most undaunted courage, will be required during the coming twelve months from all who are charged with the management of affairs in our country, or whose position gives them any influence in forming or guiding public sentiment.” “Moral courage,” says the Wilmington Journal, “the power to resist the approaches of despondency, and the faculty of communicating this power to others, will need greatly to be called into exercise; for we have reached that point in our revolution which is inevitably reached in all revolutions, when gloom and depression take the place of hope and enthusiasm—when despair is fatal and despondency is even more to be dreaded than defeat. In such a time we can understand the profound wisdom of the Roman Senate, in giving thanks to the general who had suffered the greatest disaster that ever overtook the Roman arms, ‘because he had not despaired of the Republic’ There is a feeling, however, abroad in the land, that the great crisis of the war—the turning-point in our fate—is fast approaching. Whether a crisis be upon us or not, there can be in the mind of no man, who looks at the map of Georgia, and considers her geographical relations to the rest of the Confederacy, a single doubt that much of our future is involved in the result of the next spring campaign in Upper Georgia.”

—The Fifty-second regiment of Illinois volunteers, under the command of Colonel J. S. Wilcox, reenlisted for the war, returned to Chicago. —The blockade-runner Isabel arrived at Havana. She ran the blockade at Mobile, and had a cargo of four hundred and eighty bales of cotton, and threw overboard one hundred and twenty-four bales off Tortugas, in a gale of wind.