Wednesday, 17th—The different troops are returning to camp here after destroying about one hundred and twenty-five miles of railroad, stations and all public property. All is quiet around here.

Monday, February 17, 2014

17th. Went on my way rejoicing at 9 o’clock. Found open arms at- home. How good to be here again. I couldn’t realize it down in Tenn. I am happy—one thing short! Treasure Carrie! God be praised for the blessing of home and friends.

February 17th.—Found everything in Main Street twenty per cent dearer. They say it is due to the new currency bill.

I asked my husband: “Is General Johnston ordered to reenforce Polk? They said he did not understand the order.” “After five days’ delay,” he replied. “They say Sherman is marching to Mobile.[1] When they once get inside of our armies what is to molest them, unless it be women with broomsticks?” General Johnston writes that “the Governor of Georgia refuses him provisions and the use of his roads.” The Governor of Georgia writes: “The roads are open to him and in capital condition. I have furnished him abundantly with provisions from time to time, as he desired them.” I suppose both of these letters are placed away side by side in our archives.

[1] General Polk, commanding about 24,000 men scattered throughout Mississippi and Alabama, found it impossible to check the advance of Sherman at the head of some 40,000, and moved from Meridian south to protect Mobile. February 16, 1864, Sherman took possession of Meridian.

Huntsville, Wednesday, Feb. 17. Weather cold—freezing hard. Seventeen recruits and T. J. Hungerford arrived this afternoon from the State. Thirty-six more expected soon. Two hours’ drill as usual in the morning. Parade P. M. Report of the court-martial read at parade by Adjutant Simpson. Honorably acquitted, as they did it by consent of corporal of the guard. Corporal —— arrested for granting such consent.

Alone Again.

Feb. 17. Our Brooklyn friends left us the 13th. They were ordered to report at Newport News, and we to remain here to do guard duty. When they left they expected to return in a few days, but I reckon they have gone for good, as they have sent for their ladies and quartermaster, who have gone, carrying everything with them. That leaves us alone again, and we are doing the guard duty up town, which is the outpost. It takes about one third of our men every day, and that brings us on every third day. All the camps about here are located near Fort Magruder, a large field fortification built by Gen. Magruder for the defence of Williamsburg. Since coming into Federal possession, it has been slightly altered and the guns, which formerly pointed outward, now point towards the town, about a mile distant. This was an obstacle which McClellan had to overcome in his march on Richmond. About 50 rods from its former front, now its rear, runs a wide and rather deep ravine across the country from the York to the James river, a distance of about three miles. On this line Magruder built his forts, with rifle pits in front on the edge of the ravine, for skirmishers and infantry. He had got only Fort Magruder armed on MeClellan’s arrival, but it proved a formidable obstacle, as it commanded the road and a wide piece of country. In front of this fort was the hottest of the battle, and not until Gen. Hancock with his corps had crossed the ravine at Queen’s creek on the York river side and swooped down on Magruder’s left, did he find it untenable. He then saw the day was lost and beat a hasty retreat. A few of us, while looking over the battle-ground a day or two ago, found the graves of Milford hoys, who were in the 40th New York regiment.

I reckon we must have given them quite a scare up in Richmond the other day, for in the alarm and confusion which prevailed, quite a number of prisoners escaped and are finding their way in here. Yesterday the cavalry went out to assist any that might be trying to get in.

February 17, Wednesday. Went this A.M. to Brady’s rooms with Mr. Carpenter, an artist, to have a photograph taken. Mr. C. is to paint an historical picture of the President and Cabinet at the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation.

I called to see Chase in regard to steamer Princeton, but he was not at the Department. Thought best to write him, and also Stanton. These schemes to trade with the Rebels bedevil both the Treasury and the Army.

February _ _, 1864.—By special invitation, we rode over the hills to the Camp today, to see the battalion drill. It was a dress parade and every man looked his best. I made a new (old) acquaintance after the drill was over. Frank Baker, the only son of Judge Bolling Baker, of Virginia. He is just as handsome as a picture and very pleasant. I could scarcely recall the little boy of years ago, who thought I was too small to notice. I think I must have grown just a wee bit.

The camp is beautiful; it is only a short distance from Goodwood and Aunt Sue told the boys to come over whenever they felt like it. She also offered them books to read, which offer was eagerly accepted. Tonight Mrs. Howard Gamble is giving a large party and I must stop writing and see about my dress. We cannot vary our toilettes to any extent in these days of the blockade.

(This diary was written in pencil and in many instances the dates are almost, or quite, illegible. The month and year are plain but the figures are not so plain; particularly is this the case during the years of warfare, possibly the pencils were poor, or the paper might have been. At any rate we ask our readers to be lenient if some little mistakes occur.)by John Beauchamp Jones

FEBRUARY 17TH.—Bright and very cold—freezing all day. Col. Myers has written a letter to the Secretary, in reply to our ordering him to report to the Quartermaster-General, stating that be considers himself the Quartermaster-General—as the Senate has so declared. This being referred to the President, he indorses on it that Col. Myers served long enough in the United States army to know his status and duty, without any such discussion with the Secretary as he seems to invite.

Yesterday Congress consummated several measures of such magnitude as will attract universal attention, and which must have, perhaps, a decisive influence in our struggle for independence.

Gen. Sherman, with 30,000 or 40,000 men, is still advancing deeper into Mississippi, and the Governor of Alabama has ordered the non-combatants to leave Mobile, announcing that it is to be attacked. If Sherman should go on, and succeed, it would be the most brilliant operation of the war. If he goes on and fails, it will be the most disastrous—and his surrender would be, probably, like the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown. He ought certainly to be annihilated.

I have advised Senator Johnson to let my nephew’s purpose to bring Gen. Holmes before a court-martial lie over, and I have the papers in my drawer. The President will probably promote Col. Clark to a brigadiership, and then my nephew will succeed to the colonelcy; which will be a sufficient rebuke to Gen. H., and a cataplasm for my nephew’s wounded honor.

The Examiner has whipped Congress into a modification of the clause putting assistant editors and other employees of newspaper proprietors into the army. They want the press to give them the meed of praise for their bold measures, and to reconcile the people to the tax, militia, and currency acts. This is the year of crises, and I think we’ll win.

We are now sending 400 Federal prisoners to Georgia daily; and I hope we shall have more food in the city when they are all gone.

February 16.—An engagement took place between the rebel fort at Grant’s Pass, near Mobile, and the National gunboats.—The British steamer Pet was captured by the United States gunboat Montgomery. The capture was made near Wilmington, N. C. The Pet was from Nassau, for Wilmington, with an assorted cargo of arms, shot, shell, and medicines, for the use of the rebel army. She was a superior side-wheel steamer, of seven hundred tons burthen, built in England expressly for Southern blockading purposes. She had made numerous successful trips between Nassau and Wilmington. — The blockading steamer Spunky was chased ashore and destroyed while attempting to run the blockade of Wilmington, N. C.

A naval officer’s account.

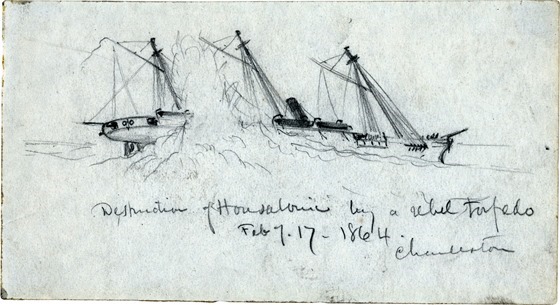

On the evening of February seventeenth, the Housatonic was anchored outside the bar, two and a half miles from Beach Inlet battery, and five miles and three fifths from the ruins of Sumter — her usual station on the blockade. There was but little wind or sea, the sky was cloudless, and the moon shining brightly. A slight mist rested on the water, not sufficient, however, to prevent our discerning other vessels on the blockade two or three miles away. The usual lookouts were stationed on the forcastle, in the gangway, and on the quarter-deck.

At about forty-five minutes past eight of the first watch, the officer of the deck discovered, while looking in the direction of Beach Inlet battery, a slight disturbance of the water, like that produced by a porpoise. At that time it appeared to be about one hundred yards distant and a-beam. The Quartermaster examined it with his glass, and pronounced it a school of fish. As it was evidently nearing the ship, orders were at once given to slip the chain, beat to quarters, and call the Captain. Just after issuing these orders, the Master’s Mate from the forcastle reported the suspicious appearance to the officer in charge. The officers and men were promptly on deck, but by this time the submarine machine was so near us that its form and the phosphorescent light produced by its motion through the water were plainly visible. At the call to quarters it had stopped, or nearly so, and then moved toward the stern of the vessel, probably to avoid our broadside guns. When the Captain reached our deck, it was on the starboard quarter, and so near us that all attempts to train a gun on it were futile. Several shots were fired into it from revolvers, and rifles; it also received two charges of buckshot from the Captain’s gun.

The chain had been slipped and the engines had just begun to move, when the crash came, throwing timbers and splinters into the air, and apparently blowing off the entire stern of the vessel. This was immediately followed by a fearful rushing of water, the rolling out of a dense, black smoke from the stack, and the settling of the vessel.

Orders were at once given to clear away the boats, and the men sprang to the work with a will. But we were filling too rapidly. The ship gave a lurch to port and all the boats on that side were swamped. Many men and some officers jumped overboard and clung to such portions of the wreck as came within reach, while others sought safety in the rigging and tops. Fortunately we were in but twenty-eight feet of water, and two of the boats on the starboard side were lowered. Most of those who had jumped overboard were either picked up or swam back to the wreck. The two boats then pulled for the Canandaigua, one and a half miles distant. Assistance was promptly rendered by that vessel to those remaining on the wreck.

At muster the next morning, five of our number were found missing. The Captain was thrown several feet into the air by the force of the explosion, and was painfully but not dangerously bruised and cut.

It was the opinion of all who saw the strange craft, that it was very nearly or entirely under water, that there was no smoke-stack, that it was from twenty to thirty feet in length, and that it was noiseless’ in its motion through the water. It was not seen after the explosion. The ship was struck on the starboard side abaft the mizzen-mast. The force of the explosion seems to have been mainly upward. A piece ten feet square was blown out of her quarter-deck, all the beams and carlines being broken transversely across. The heavy spanker-boom was broken in its thickest part, and the water for some distance was white with splinters of oak and pine.

Probably not more than one minute elapsed from the time the torpedo was first seen, until we were struck, and not over three or four minutes could have passed between the explosion and the sinking of the ship. Had we been struck in any other part, or before the alarm had been given, the loss of life would have been much greater.

The Housatonic was a steam-sloop, with a tonnage of one thousand two hundred and forty, and she carried a battery of thirteen guns. She was completed about eighteen months ago, and has been in the blockade ever since. She is the first vessel destroyed by a contrivance of this character, and this fact gives to this lamentable affair a significance which it would not otherwise possess. Deserters tell us that there are other machines of this kind in the harbor, ready to come out, and that several more are in process of construction. The country cannot attend too earnestly to the dangers which threaten our blockading fleets, and the gunboats and steamers on the Southern rivers.

X. off Charleston, February 22, 1864.

Order by Admiral Dahlgren.

Flag-steamer Philadelphia,

Port Royal harbor, S. C.,

Feb. 19, 1864.

Order no. 50:

The Housatonic has just been torpedoed by a rebel David, and sunk almost instantly.

It was at night, and the water smooth.

The success of this undertaking will, no doubt, lead to similar attempts along the whole line of blockade.

If vessels on blockade are at anchor, they are not safe, particularly in smooth water, without out-riggers and hawsers, stretched around with rope netting, dropped in the water.

Vessels on inside blockade had better take post outside at night, and keep underweigh, until these preparations are completed.

All the boats must be on the patrol when the vessel is not in movement.

The commanders of vessels are required to use their utmost vigilance — nothing less will serve.

I intend to recommend to the Navy Department the assignment of a large reward, as prize-money, to crews or vessels who shall capture, or, beyond doubt, destroy one of these torpedo boats.

John A. Dahlgren,

Rear-Admiral, Commanding

S. A. B. Squadron.