A naval officer’s account.

On the evening of February seventeenth, the Housatonic was anchored outside the bar, two and a half miles from Beach Inlet battery, and five miles and three fifths from the ruins of Sumter — her usual station on the blockade. There was but little wind or sea, the sky was cloudless, and the moon shining brightly. A slight mist rested on the water, not sufficient, however, to prevent our discerning other vessels on the blockade two or three miles away. The usual lookouts were stationed on the forcastle, in the gangway, and on the quarter-deck.

At about forty-five minutes past eight of the first watch, the officer of the deck discovered, while looking in the direction of Beach Inlet battery, a slight disturbance of the water, like that produced by a porpoise. At that time it appeared to be about one hundred yards distant and a-beam. The Quartermaster examined it with his glass, and pronounced it a school of fish. As it was evidently nearing the ship, orders were at once given to slip the chain, beat to quarters, and call the Captain. Just after issuing these orders, the Master’s Mate from the forcastle reported the suspicious appearance to the officer in charge. The officers and men were promptly on deck, but by this time the submarine machine was so near us that its form and the phosphorescent light produced by its motion through the water were plainly visible. At the call to quarters it had stopped, or nearly so, and then moved toward the stern of the vessel, probably to avoid our broadside guns. When the Captain reached our deck, it was on the starboard quarter, and so near us that all attempts to train a gun on it were futile. Several shots were fired into it from revolvers, and rifles; it also received two charges of buckshot from the Captain’s gun.

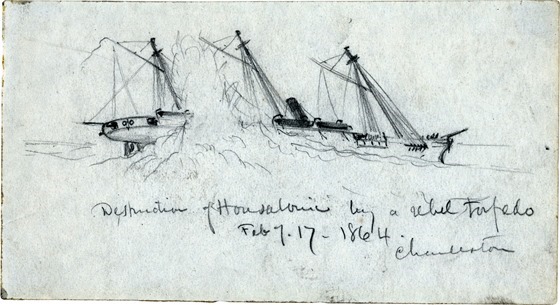

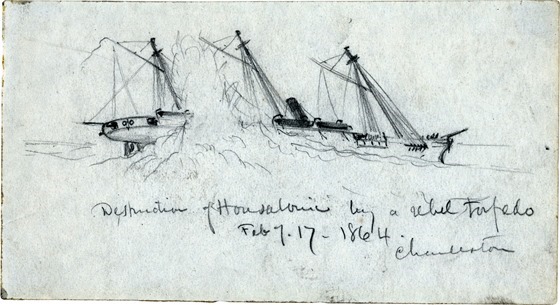

The chain had been slipped and the engines had just begun to move, when the crash came, throwing timbers and splinters into the air, and apparently blowing off the entire stern of the vessel. This was immediately followed by a fearful rushing of water, the rolling out of a dense, black smoke from the stack, and the settling of the vessel.

Orders were at once given to clear away the boats, and the men sprang to the work with a will. But we were filling too rapidly. The ship gave a lurch to port and all the boats on that side were swamped. Many men and some officers jumped overboard and clung to such portions of the wreck as came within reach, while others sought safety in the rigging and tops. Fortunately we were in but twenty-eight feet of water, and two of the boats on the starboard side were lowered. Most of those who had jumped overboard were either picked up or swam back to the wreck. The two boats then pulled for the Canandaigua, one and a half miles distant. Assistance was promptly rendered by that vessel to those remaining on the wreck.

At muster the next morning, five of our number were found missing. The Captain was thrown several feet into the air by the force of the explosion, and was painfully but not dangerously bruised and cut.

It was the opinion of all who saw the strange craft, that it was very nearly or entirely under water, that there was no smoke-stack, that it was from twenty to thirty feet in length, and that it was noiseless’ in its motion through the water. It was not seen after the explosion. The ship was struck on the starboard side abaft the mizzen-mast. The force of the explosion seems to have been mainly upward. A piece ten feet square was blown out of her quarter-deck, all the beams and carlines being broken transversely across. The heavy spanker-boom was broken in its thickest part, and the water for some distance was white with splinters of oak and pine.

Probably not more than one minute elapsed from the time the torpedo was first seen, until we were struck, and not over three or four minutes could have passed between the explosion and the sinking of the ship. Had we been struck in any other part, or before the alarm had been given, the loss of life would have been much greater.

The Housatonic was a steam-sloop, with a tonnage of one thousand two hundred and forty, and she carried a battery of thirteen guns. She was completed about eighteen months ago, and has been in the blockade ever since. She is the first vessel destroyed by a contrivance of this character, and this fact gives to this lamentable affair a significance which it would not otherwise possess. Deserters tell us that there are other machines of this kind in the harbor, ready to come out, and that several more are in process of construction. The country cannot attend too earnestly to the dangers which threaten our blockading fleets, and the gunboats and steamers on the Southern rivers.

X. off Charleston, February 22, 1864.

Order by Admiral Dahlgren.

Flag-steamer Philadelphia,

Port Royal harbor, S. C.,

Feb. 19, 1864.

Order no. 50:

The Housatonic has just been torpedoed by a rebel David, and sunk almost instantly.

It was at night, and the water smooth.

The success of this undertaking will, no doubt, lead to similar attempts along the whole line of blockade.

If vessels on blockade are at anchor, they are not safe, particularly in smooth water, without out-riggers and hawsers, stretched around with rope netting, dropped in the water.

Vessels on inside blockade had better take post outside at night, and keep underweigh, until these preparations are completed.

All the boats must be on the patrol when the vessel is not in movement.

The commanders of vessels are required to use their utmost vigilance — nothing less will serve.

I intend to recommend to the Navy Department the assignment of a large reward, as prize-money, to crews or vessels who shall capture, or, beyond doubt, destroy one of these torpedo boats.

John A. Dahlgren,

Rear-Admiral, Commanding

S. A. B. Squadron.