Lowell, Mass., Nov. 26,1860.

My Dear Sir,—Your letter was received at Concord on Saturday, and I should have answered it while there if I could have found a little interval of leisure. I am here to-day on business, and can therefore do scarcely more than to thank you; but let so much, at least, be said. The apprehensions which you so forcibly express did not increase mine. You know how sincerely and earnestly I have for years deprecated the causes which, if not removed, I foresaw must produce the fearful crisis which is now upon us; and I know how ineffectual, in this section, have been all warnings of patriotism and ordinary forecast. Now, for the first time, men are compelled to open their eyes, as if aroused from some strange delusion, upon a full view of the nearness and magnitude of impending calamities. It is worse than idle—it is foolhardy—to discuss the question of probable relative suffering and loss in different sections of the Union. In case of disruption we shall all be involved in common financial embarrassment and ruin, and, I fear, in common destruction so much more appalling than any attendant upon mere sacrifice of property, that one involuntarily turns from its contemplation. To my mind one thing is clear: no wise man can, under existing circumstances, dream of coercion. The first blow struck in that direction will be a blow fatal even to hope.

You have observed, of course, how seriously commercial confidence, and consequently the price of stocks, etc., have already been shaken at the North, and yet there is in the public mind a very imperfect apprehension of the danger. Still, there are indications of a disposition to repeal laws directed against the constitutional rights of the Southern States,— such as personal liberty bills, etc.—and if we could gain a little time, there would seem to be ground of hope that these just causes of distrust and dissatisfaction may be removed. I trust the South will make a large draft on their devotion to the Union, and be guided by the wise moderation which the exigency so urgently calls for. Can it be that this flag, with all the stars in their places, is no longer to float, at home, abroad, and always, as an emblem of our united power, common freedom, and unchallenged security? Can it be that it is to go down in darkness, if not in blood, before we have completed a single century of our independent national existence? I agree with you that madness has ruled the hour in pushing forward a line of aggressions upon the South, but I will not despair of returning reason and of a re-awakened sense of constitutional right and duty. I will still look with earnest hope for the full and speedy vindication of the co-equal rights and co-equal obligations of these States, and for restored fraternity under the present Constitution— fraternity secured by following the example of the fathers of the republic—fraternity based upon admission and cheerful maintenance of all the provisions and requirements of the sacred instrument under which they and their children have been so signally blessed. When that hope shall perish, if perish it must, life itself, my friend, will lose its value for you and me. It is apparent that much will depend upon the views expressed and the tone and temper manifested during the early days of the session of Congress now near at hand. May the God of our fathers guide the counsels of those who in the different departments of government are invested in this critical epoch with responsibilities unknown since the sitting of the convention which framed the Constitution.

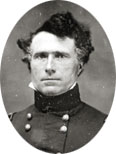

Your friend,

Franklin Pierce.