London, May 14, 1863

The telegraph assures us that Hooker is over the Rappahannock and your division regally indistinct “in the enemy’s rear.” I suppose the campaign is begun, then. Honestly, I’d rather be with you than here, for our state of mind during the next few weeks is not likely to be very easy.

But now that things are begun, I will leave them to your care. Just for your information, I inclose one of Mr. Lawley’s letters from Richmond to the London Times. It is curious. Mr. Lawley’s character here is under a cloud, as, strange to say, is not unusual with the employes of that seditious journal. For this and other reasons I don’t put implicit trust in him, but one fact is remarkably distinct. His dread of the shedding of blood makes him wonderfully anxious for intervention. A prayer for intervention is all that the northern men read in this epistle, and Mr. Lawley’s humanity does n’t quite explain his earnestness. . . .

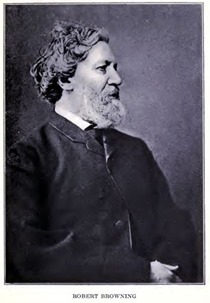

It was a party of only eleven, and of these Sir Edward [Lytton] was one, Robert Browning another, and a Mr. Ward, a well known artist and member of the Royal Academy, was a third. All were people of a stamp, you know; as different from the sky-blue, skim-milk of the ball-rooms, as good old burgundy is from syrup-lemonade. I had a royal evening; a feast of remarkable choiceness, for the meats were very excellent good, the wines were rare and plentiful, and the company was of earth’s choicest.

Sir Edward is one of the ugliest men it has been my good luck to meet. He is tall and slouchy, careless in his habits, deaf as a ci-devant, mild in manner, and quiet and philosophic in talk. Browning is neat, lively, impetuous, full of animation, and very un-English in all his opinions and appearance. Here, in London Society, famous as he is, half his entertainers actually take him to be an American. He told us some amusing stories about this, one evening when he dined here.

Sir Edward is one of the ugliest men it has been my good luck to meet. He is tall and slouchy, careless in his habits, deaf as a ci-devant, mild in manner, and quiet and philosophic in talk. Browning is neat, lively, impetuous, full of animation, and very un-English in all his opinions and appearance. Here, in London Society, famous as he is, half his entertainers actually take him to be an American. He told us some amusing stories about this, one evening when he dined here.

Just to amuse you, I will try to give you an idea of the conversation after dinner; the first time I have ever heard anything of the sort in England. Sir Edward is a great smoker, and although no crime can be greater in this country, our host produced cigars after the ladies had left, and we filled our claret-glasses and drew up together.

Sir Edward seemed to be continuing a conversation with Mr. Ward, his neighbor. He went on, in his thoughtful, deliberative way, addressing Browning.

“Do you think your success would be very much more valuable to you for knowing that centuries hence, you would still be remembered? Do you look to the future connection by a portion of mankind, of certain ideas with your name, as the great reward of all your labor?”

“Not in the least! I am perfectly indifferent whether my name is remembered or not. The reward would be that the ideas which were mine, should live and benefit the race!”

“I am glad to hear you say so,” continued Sir Edward, thoughtfully, “because it has always seemed so to me, and your opinion supports mine. Life, I take to be a period of preparation. I should compare it to a preparatory school. Though it is true that in one respect the comparison is not just, since the time we pass at a preparatory school bears an infinitely greater proportion to a life, than a life does to eternity. Yet I think it may be compared to a boy’s school; such a one as I used to go to, as a child, at old Mrs. S’s at Fulham. Now if one of my old school-mates there were to meet me some day and seem delighted to see me, and asked me whether I recollected going to old mother S’s at Fulham, I should say, ‘Well, yes. I did have some faint remembrance of it! Yes. I could recollect about it.’ And then supposing he were to tell me how I was still remembered there! How much they talked of what a fine fellow I’d been at that school.”

“How Jones Minimus,” broke in Browning, “said you were the most awfully good fellow he ever saw.”

“Precisely,” Sir Edward went on, beginning to warm to his idea. “Should I be very much delighted to hear that? Would it make me forget what I am doing now? For five minutes perhaps I should feel gratified and pleased that I was still remembered, but that would be all. I should go back to my work without a second thought about it.

“Well now, Browning, suppose you, sometime or other, were to meet Shakespeare, as perhaps some of us may. You would rush to him and seize his hand, and cry out, ‘My dear Shakespeare, how delighted I am to see you. You can’t imagine how much they think and talk about you on the earth!’ Do you suppose Shakespeare would be more carried away by such an announcement than I should be at hearing that I was still remembered by the boys at mother S’s at Fulham? What possible advantage can it be to him to know that what he did on the earth is still remembered there?”

The same idea is in LXII of Tennyson’s In Memoriam, but not pointed the same way. It was curious to see two men who, of all others, write for fame, or have done so, ridicule the idea of its real value to them. But Browning went on to get into a very unorthodox humor, and developed a spiritual election that would shock the Pope, I fear. According to him, the minds or souls that really did develope themselves and educate themselves in life, could alone expect to enter a future career for which this life was a preparatory course. The rest were rejected, turned back, God knows what becomes of them, these myriads of savages and brutalized and degraded Christians. Only those that could pass the examination were allowed to commence the new career. This is Calvin’s theory, modified; and really it seems not unlikely to me. Thus this earth may serve as a sort of feeder to the next world, as the lower and middle classes here do to the aristocracy, here and there furnishing a member to fill the gaps. The corollaries of this proposition are amusing to work out.