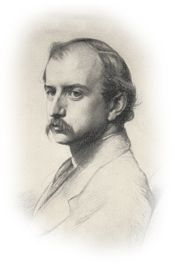

Henry Adams to Charles Francis Adams, Jr.

London, September 16, 1863

When I came to the end of my long volume of travels, I intimated to you that I had found things here in a very bad way on my return. We were in fact in the middle of the crisis which I have so often warned you would be the dangerous and decisive one; and now it was going against us.

You have heard much of the two iron-clads now building at Liverpool; formidable vessels which would give us trouble. Ever since their keels were laid, now some eighteen months since, we have been watching them with great anxiety. Luckily they were not at first pressed forward very rapidly, and the delay has given us just the time we needed. But we have never attempted to disguise to the people here, what would be the inevitable result of their being allowed to go, and both Mr. Evarts and all our other supernumerary diplomats have urged with the greatest energy some measure of effective interference. This had been so far successful that we had felt tolerably secure under what appeared to be decisive assurances. As the summer wore on, the vessels were launched and began to fit for sea. Our people, as in the case of the Alabama and Alexandra, were busy in getting up a case, and sent bundles of depositions and letters into the Foreign Office. This was the position of affairs when I left London, and although I am violating the rules by telling you about it, I suppose the facts are so public and so well understood that there would be no great harm if anyone knew it. But what has since passed is as yet known to but few and not understood even by them, in which number I include myself.

The law officers of the Crown were funky, as the boys say here. They were not willing to advise the seizure of the vessels under the Neutrality Act. In this respect I think they were right, for although there was perhaps a case strong enough to justify the arrest of the vessels, it was certainly not strong enough to condemn them, and it would have been too absurd to have had another such ludicrous sham as the trial of the Alexandra, where Mr. Evarts acted as drill-sergeant, and the prosecution was carried just so far and no farther than was necessary to show him that everything was on the square. The result, as declared by Chief Baron Pollock, was the most amusing example of the admired English system that has yet taken place, and if my ancient Anglomania, which swallowed Blackstone, and bowed before the Judges’ wigs, had not yielded to a radical disbelief in the efficacy of England already, I believe this solemn and ridiculous parade of the majesty and imperturbability of English justice would have given such a shock to my old notions as they never would have recovered from.

The law-officers were right therefore, in my opinion, in wishing to escape this disgrace, for unless the work was to be done in a very different spirit from the last job, it would be a disgrace, and they knew it. In fact this was no longer a case for the Courts. Any Government which really assumes to be a Government, and not a Governed-ment, would long ago have taken the matter into its own hands and made the South understand that this sort of thing was to be stopped. But this form of Government is the snake with many heads. It may be accidentally successful, and so exist from mere habit and momentum; but it is as a system, clumsy, unmanageable, and short-lived. You will laugh at my word short-lived, and think of William the Conqueror. You might as well think of Justinian. This Government, as it stands today, is just thirty years old, and between a reformed Government under the Reform Bill and an aristocratic Government and nomination boroughs, there is as much difference as between the France of Louis Philippe and the France of Louis Quinze.

At any rate, the English having in their hatred of absolute Government rendered all systematic Government impossible, now inflict upon us the legitimate fruits of their wisdom. On a question which is so evident that no other Government ever hesitated to acknowledge its duties; not even England herself in former days; it now comes to a dead-lock. The springs refuse to work. The cog-wheels fly round wildly in vain, and Lord Russell, after repeated attempts to grind something out of his poor mill, at last is compelled to inform us that he is very sorry but it won’t work, and as for the vessels, Government can’t stop them and won’t try.

It was just after the receipt of this information that I reached London. You may imagine our condition, and the little disposition we felt to shirk the issue, when the same day brought us the story of Gilmore’s big guns and Sumter’s walls. In point of fact, disastrous as a rupture would be, we have seen times so much blacker that we were not disposed to bend any longer even if it had been possible. The immediate response to this declaration was a counter-declaration, short but energetic, announcing what was likely to happen, Lord Russell is in Scotland and this produced some confusion in the correspondence, but it was rapid and to me very incomprehensible. My suspicion is that they meant to play us, like a salmon, and that the note of which I speak fell so hard as to break the little game. At all events, within three, days came a short announcement that the vessels should not leave.

Undoubtedly to us this is a second Vicksburg. It is our diplomatic triumph, if we manage to carry it through. You will at once understand how very deeply our interests depend on it, and under the circumstances, how great an achievement our success will be. It would in fact be the crowning stroke of our diplomacy. After it, we might say our own minds to the world and do our own will. A public life seldom affords to a man the opportunity to perform more than one or two brilliant roles of this description, and no more is needed in order to set his mark on history. Whether we shall succeed, I am not yet certain. The vessels are only detained temporarily, but the signs are that the gale that has blown so long is beginning to veer about. If our armies march on; if Charleston is taken and North Carolina freed; above all if emancipation is made effective; Europe will blow gentle gales upon us and will again bow to our dollars. Every step we make, England makes one backward. But if we have disaster to face, then indeed I can’t say. Yet I am willing to do England the justice to say that while enjoying equally with all nations the baseness which is inevitable to politics carried on as they must be, she still has a conscience, though it is weak, ineffective and foggy. Usually after she has got herself into some stupid scrape, her first act is to find out she is wrong and retract when too late. I think the discussion which is now taking place has pretty much convinced most people that this war-vessel matter is one that ought to be stopped. And if so, the mere fact that they have managed to take the first step is to me reasonable ground for confidence that they will take the others as the emergencies arise. There will be hoisting and straining, groaning and kicking, but the thing will in some stupid and bungling way be got done.

Meanwhile volumes are written. To read them is bad enough, but to write them! I believe this to be really of little effect, and think I see the causes of movement in signs entirely disconnected with mere argument. The less said, the shorter work. Give us no disasters, and we have a clear and convincing position before the British public, for we come with victories on our standards and the most powerful military and naval engines that ever the earth saw. Unceasing military progress. The rebels are crying to high Heaven on this side for some one to recognize them. A few months more and it will be too late, if it’s not already.