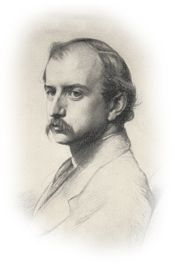

Henry Adams, private secretary of the US Minister to the UK, to his brother, Charles.

London, October 28, 1864

The results of the October elections are just beginning to make themselves clear to us. They indicate precisely what I have always most dreaded, namely a closely contested Presidential vote. I only judge by the Pennsylvania election, where the Democrats seem to have carried everything. How it may be in Ohio and Indiana I do not know, but I fear a similar result. They gain just enough to place Lincoln in a very weak position if he is elected. These ups and downs have been so frequent for the last four years that I am not disposed to put too much weight on them. At the same time I cannot help remembering that a down turn just at this moment is a permanent thing. It gives us our direction for a long time. But I must see our papers before I can fairly understand what is to happen. Meanwhile there appears to be a hitch in army affairs and some mysterious trouble there. This is also rather blue. . . .

In fact we are now under any circumstances within four or five months of our departure from this country. I am looking about with a sort of vague curiosity for the current which is to direct my course after I am blown aside by this one. If McClellan were elected, I do not know what the deuce I should do. Certainly I should not then go into the army. Anyway I’m not fit for it, and to come in when the anti-slavery principle of the war is abandoned, and a peace party in power, would be out of my cards. I think in such a case I should retire to Cambridge and study law and other matters which interest me. Once a lawyer, I have certain plans of my own. I do not however believe that McClellan’s election can much change the political results of things, and although it may exercise a great influence on us personally, I believe a little waiting will set matters right again. So a withdrawal to the shades of private life for a year or two, will perhaps do us all good. If that distinguished officer would only beat us all to pieces! But if Lincoln is elected by a mere majority of electors voting, not by a majority of the whole electoral college; if Grant fails to drive Lee out of Richmond; if the Chief is called to Washington to enter a Cabinet with a species of anarchy in the North and no probability of an end of the war — then, indeed, I shall think the devil himself has got hold of us, and shall resign my soul to the inevitable. This letter will reach you just on the election. My present impression is that we are in considerable danger of all going to Hell together. You can tell me if I am right.