Headquarters Second Vermont Brigade, Wolf Run Shoals, Va., April 9, 1863.

Dear Free Press:

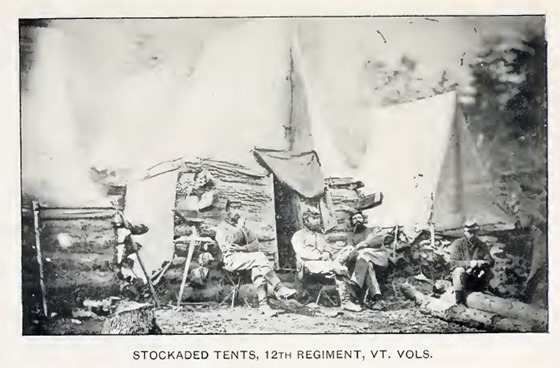

If I sometimes talk about the weather it is because it is a subject of prime importance in every camp. Upon the weather depend both the movements of armies and the health of the troops, to an extent which can hardly be realized by any one not connected with the army. The risks the soldier thinks most about when he first enlists, are commonly those of the battlefield. After he has been out a while, not wounds or death or capture, but sickness, is his great dread. As long as he is well, if he is a true man, he cares little about the rest. For a month past we have encouraged ourselves with the thought that the season of snows and mud was about over. The inhabitants hereabouts told us that they frequently commenced ploughing in February, and that such gardens as they have were always made or making by the middle of March. This may be so; but we have no evidence of the fact this year. If you could have heard the storm howl here last Saturday night, or seen the pickets wading to their posts next day through snow which frequently in the hollows was over boot tops, you would have come to the conclusion that winter was not “rotting in the sky” in Virginia. To-day the snow still lies upon the shaded hill-slopes, and the air is as chilly, in spite of the sunshine, as in any April day in Vermont. We have now done counting on the speedy return of mild and pleasant weather. It may come, when it pleases the kind Ruler of the sunshine and the storm; but our boys declare that they shall not be surprised to leave Virginia in a snow storm when our time is out next July. The sick list of the Twelfth is larger now than ever before, numbering not less than 120, besides a number who suffer from severe colds but are not sick enough to require the surgeon’s care. This diminution from the effective force of the regiment, while the details for picket duty are increased rather than diminished, tells sensibly upon the labors of the well and strong. But while there is some complaining, of course, all are ready to own that they had far rather do the work of the sick and feeble ones, than to take their places in the hospitals. There have been one or two more deaths since I wrote you last. The Twelfth, heretofore the healthiest, seems to be now the sickliest regiment in the brigade. Why this is so, it is hard to explain. Partly, perhaps, because the other regiments had their “sick spells” and got through the process of acclimation sooner; partly because the measles had a run in the winter and left many men in poor condition to resist the exposures of the spring; partly, perhaps mainly, owing to the unhealthy location of the camp. The last reason will not hold after this. This week the regiment has moved camp to a hard-wood knoll, a quarter of a mile from the old one. The location is higher and the ground much better than the old one. The men erected new stockades before they left the old ones, and when the mud dries will be very comfortable in their new quarters. I wish you could look into some of the new shanties, and see how comfortable. I have one of Company C’s in my eye— stockade of logs, split in halves, laid flat side in and hewed smooth, a good five feet high and closely covered by the canvas roof; door of boards in one side; good floor of pieces of hard tack boxes; bunks wide enough for two men, one over the other, made of smooth poles which make a spring bedstead; sheet iron stove; sofa of split white wood, without ends or back; gun rack filled with its shining arms—the principal ornament of the room; shelves, pegs to hang things on, and other conveniences too numerous to mention—why, it is good enough for the honeymoon palace of the Princess and Prince of Wales, good enough even for a soldier of the Army of the Union.

This brigade is now picketing twenty odd miles of line. The Fourteenth guards the lower Occoquan from the lowest ford at Colchester to Davis’s Ford, three miles below the Shoals. The Twelfth and Thirteenth picket from there to Yates’s Ford,. a couple of miles below Union Mills. The Fifteenth and Sixteenth take care of the rest of the line up to Blackburn’s Ford, on Bull Run, where the pickets of General Hays’ brigade meet our own.

The men of the Twelfth have been gratified by the recent removal of the headquarters of the brigade to the vicinity of the Shoals, thus bringing Colonel Blunt in a measure back to them, and the colonel is as glad to be near his regiment as they are to have him here.

Our pickets have been repeatedly fired on at night of late by bushwhackers. The consequence is stricter measures with the inhabitants within and near our lines. Brigade Provost Marshal, Captain William Munson, has been visiting all the houses in this region, searching for and confiscating all arms and property contraband of war, and registering the names and standing as to loyalty, of the citizens. It goes hard with some of these F. F. V’s, to give up the old fowling pieces, of which quite a collection is accumulating at headquarters, some of them nearly as long as Long Bridge, and old as the invention of gunpowder apparently, which have been handed down from father to son for generations; but they have to come.

It is one of the most embarrassing portions of the duty of a commanding officer in such a region as this, to deal properly with the noncombatant inhabitants. The innocent must often suffer with the guilty, from the nature of the case. Colonel Blunt is kind to the sincerely loyal, of whom there are very few, and to the inoffensive, of whom there are more, within our lines, and is looked up to by them as a protector; but the men whose influence contributed to bring about the present state of things, whose sons are in the rebel army, and whose sympathies are with that side, get little consolation when they come to Colonel Blunt to complain. They are informed that as they would have secession and war, and have sown the wind, they must take the consequences and reap the whirlwind. Such dialogues as the following are not infrequent: Citizen, “Good morning, Colonel,” Colonel, “Good morning, sir.”—Citizen, “My name is ——;your troops are stealing my rails; I’d like to save what I’ve got left, and wish you’d order them that ain’t burnt brought back, and stop them taking any more.” Colonel, “H’m, did you vote for secession?” Citizen, “Well,”(hesitating,) “Well I did, colonel, but it is too late to talk about that now.” Colonel, “Too late to talk about rails, too, sir. Good day, sir.” Exit citizen with a large flea in his ear and rage in his heart at “the d—d Yankees.”

But to return to the provost marshal’s operations, I was going to say that enough of information and arms have been obtained to fully warrant the search. Muskets have been found hid in the closets, and cartridges and percussion caps by thousands laid away in the women’s bureau drawers, the possession of which they relinquished with extreme reluctance. Some citizens have been sent in to Washington for safe custody, and it is hoped that this playing peaceful citizen by day and bushwhacker by night is measureably stopped, for the present. Captain Munson has performed his delicate duties, so far as I can learn, with great good judgment and efficiency.

We turn back now from our lines remorselessly all fugitives from Dixie, except contrabands and deserters from the rebel army. Three of them came in to-day, one of them a young man of 25, the other two good looking boys of 17, all of the Fifth Virginia cavalry. They are clothed in the coarse cotton and wool butternut colored jackets and trousers which commonly form the uniform of a rebel soldier when he has one; and tell the often repeated story of scanty rations, hard treatment, and poor pay. The twelve dollars a month which they are paid barely cover the cost of their clothes, at the rates at which they are charged to them, so that the rebel soldier in fact works for his food and clothing, and not over much of either. One of these was a Baltimore boy who joined the rebel army in a hurry, on its invasion of Maryland seven months ago, and has repented at his leisure. They brought their carbines with them, and tell straight stories. They say that an impression that the war is to continue indefinitely prevails now in the South, and is disheartening many who have hitherto held out strongly for the rebel cause.

This being fast day in Vermont, a general order from the colonel commanding directed the relief of the men from all unnecessary duties, and the observance of religious exercises appropriate to the occasion. The unsettled state of the camp of the Twelfth prevented our chaplain from preaching a sermon. I attended divine service in the camp of the Fourteenth and heard a patriotic and excellent sermon by Chaplain Smart of that regiment.

Yours, B.