MAY 15TH.—The familiar “Attention, battalion!” was heard from our Colonel, when we marched back upon the same road that had led us to Jackson, camping as usual at dark. We passed through Clinton, and the inhabitants were surprised to see us returning so soon, for they fully expected to hear of our being defeated and driven back. But they did not know our metal. The last few days have been full of excitement, and although we have marched and fought hard, and lost some of our best men, besides getting tired and hungry ourselves, we are more resolved than ever to keep the ball rolling. The thinner our ranks are made by fighting and disease, the closer together the remnants are brought. We shall close up the ranks and press forward until the foe is vanquished. Soldiers grow more friendly as they are brought better to realize the terrible ravages of war. As Colonel Force called us to “Attention!” this morning, one of the boys remarked, “I love that man more than ever.” Yes, we have good reason to be proud of our Colonel, for upon all occasions we are treated by him as volunteers enlisted in war from pure love of country, and not regulars, drawn into service from various other motives, in time of peace.

A Soldier’s Story of the Siege of Vicksburg–Osborn H. Oldroyd

MAY 14TH.—Started again this morning for Jackson. When within five miles of the city we heard heavy firing. It has rained hard to-day and we have had both a wet and muddy time, pushing at the heavy artillery and provision  wagons accompanying us when they stuck in the mud. The rain came down in perfect torrents. What a sight ! Ambulances creeping along at the side of the track—artillery toiling in the deep ruts, while Generals with their aids and orderlies splashed mud and water in every direction in passing. We were all wet to the skin, but plodded on patiently, for the love of country.

wagons accompanying us when they stuck in the mud. The rain came down in perfect torrents. What a sight ! Ambulances creeping along at the side of the track—artillery toiling in the deep ruts, while Generals with their aids and orderlies splashed mud and water in every direction in passing. We were all wet to the skin, but plodded on patiently, for the love of country.

When within a few miles of Jackson, the news reached us that Sherman had slipped round to the right and captured the place, and the shout that went up from the men on the receipt of that news was invigorating to them in the midst of trouble. I think they could have been heard in Jackson. Sherman’s army at the right and McPherson in our immediate front, with one desperate charge we ran without stopping till we reached the town. The flower of the confederate forces, the pride of the Southern States who had never yet known defeat, came up to Jackson last night to help demolish Grant’s army, but for once they failed. Veterans of Georgia stationed as reserves were also forced to yield in dismay, and never stopped retreating till they had passed far south of the Capital which they had striven so valiantly to defend. To-night the stars and stripes float proudly over the cupola of the seat of government of Mississippi—and if my own regiment has not had a chance to-day to cover itself with glory it has with mud.

I shall not soon forget the conversation I have had with a wounded rebel. He said that his regiment last night was full of men who had never before met us, and who felt sure it would be easy to whip us. How they were deceived! He said part of his regiment was behind a hedge fence, where they felt comparatively safe, but the Yankees jumped right over without stopping, and swept everything before them. I never saw finer looking men than the killed and wounded rebels of to-day, and with the smooth face of one of them, lying in a garden mortally wounded, I was so taken, that I eased his thirst with a drink from my own canteen. His piteous glance at me at that time I shall never forget. It is on the battle field and among the dead and dying we get to know each other better—nay, even our own selves. Administering to a stranger, we think of his mother’s love, as dear to him as our own to us. When the fight is over, away all bitterness. Let us leave with the foe some tokens of good will, that, when the cruel war at last is over, may be kindly remembered. I trust our enemies may yet be led to hail in good faith the return of peace and the restoration of the Union. This is a domestic war, the saddest of all, being fought between those whose hearts should be as brothers; and when it is at an end, may those hearts again throb together beneath the folds of the flag that once waved for defence over their sires and themselves —a flag whose proud motto will be, “peace on earth and good will to men.”

Some of the boys went down into the city to view our new possession. It seems ablaze, but I trust only public property is being destroyed, or such as might aid and comfort the enemy hereafter.

I am very tired, and of course can easily get excused, so I will go to my bed on the ground.

MAY 13TH.—Up early, and on the march to Jackson, as we suppose.

I dreamed of my bunk-mate last night. Wonder if his remains will be put where they can be found, for I would like, if I ever get the chance, to put a board with his name on it at the head of his grave. When we enlisted we all paired off, each selecting his comrade—such a one as would be congenial and agreeable to him—and as yesterday’s battle broke a good many such bonds, new ties have been forming,—as the boys say, new couples are getting married. If married people could always live as congenial and content as two soldiers sleeping under the same blanket, there would be more happiness in the world. I shall await the return of one of the wounded.

We arrived at Clinton after dark, a place on the Jackson and Vicksburg railroad. Yesterday a train ran through, the last that will ever be run by confederates. The orders are to destroy the road here in each direction. We expected to have to fight for this spot, but instead we took possession unmolested. “Cotton is king,” and finding a good deal here, we have made our beds of it.

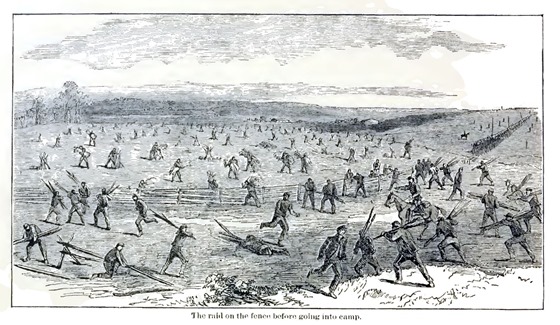

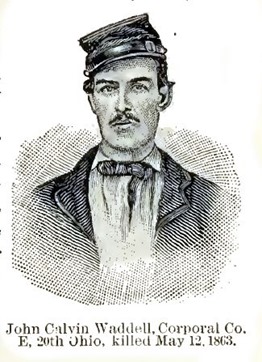

MAY 12TH—Roused up early and before daylight marched, the 20th in the lead. Now we have the honored position, and will probably get the first taste of battle. At nine o’clock slight skirmishing began in front, and at eleven we filed into a field on the right of the road, where another regiment joined us on our right, with two other regiments on the left of the road and a battery in the road itself. In this position our line marched down through open fields until we reached the fence, which we scaled and stacked arms in the edge of a piece of timber. No sooner had we done this than the boys fell to amusing themselves in various ways, taking little heed of the danger about to be entered. A group here and there were employed in “euchre,” for cards seem always handy enough where soldiers are. Another little squad was discussing the scenes of the morning. One soldier picked up several canteens, saying he would go ahead and see if he could fill them. Soon after he disappeared, he returned with a quicker pace and with but one canteen full, saying, when asked why he came back so quick—”while I was filling the canteen I heard a noise, and looking up discovered several Johnnies behind trees, getting ready to shoot, and I concluded I would retire at once and report.” Meanwhile my bedfellow had taken from his pocket a small mirror and was combing his hair and moustache. Said some one to him. “Cal., you needn’t fix up so nice to go into battle, for the rebs won’t think any better of you for it.”

Just here the firing began in our front, and we got orders : “Attention ! Fall in—take arms—forward—double-quick, march!” And we moved quite lively, as the rebel bullets did likewise. We had advanced but a short distance—probably a hundred yards—when we came to a creek, the bank of which was high, but down we slid, and wading through the water, which was up to our knees, dropped upon the opposite side and began firing at will. We did not have to be told to shoot, for the enemy were but a hundred yards in front of us, and it seemed to be in the minds of both officers and men that this was the very spot in which to settle the question of our right of way. They fought desperately, and no doubt they fully expected to whip us early in the fight, before we could get reinforcements. There was no bank in front to protect my company, and the space between us and the foe was open and perfectly level. Every man of us knew it would be sure death to all to retreat, for we had behind us a bank seven feet high, made slippery by the wading and climbing back of the wounded, and where the foe could be at our heels in a moment. However, we had no idea of retreating, had the ground been twice as inviting; but taking in the situation only strung us up to higher determination. The regiment to the right of us was giving way, but just as the line was wavering and about to be hopelessly broken, Logan dashed up, and with the shriek of an eagle turned them back to their places, which they regained and held. Had it not been for Logan’s timely intervention, who was continually riding up and down the line, firing the men with his own enthusiasm, our line would undoubtedly have been broken at some point. For two hours the contest raged furiously, but as man after man dropped dead or wounded, the rest were inspired the more firmly to hold fast their places and avenge the fallen. The creek was running red with precious blood spilt for our

Just here the firing began in our front, and we got orders : “Attention ! Fall in—take arms—forward—double-quick, march!” And we moved quite lively, as the rebel bullets did likewise. We had advanced but a short distance—probably a hundred yards—when we came to a creek, the bank of which was high, but down we slid, and wading through the water, which was up to our knees, dropped upon the opposite side and began firing at will. We did not have to be told to shoot, for the enemy were but a hundred yards in front of us, and it seemed to be in the minds of both officers and men that this was the very spot in which to settle the question of our right of way. They fought desperately, and no doubt they fully expected to whip us early in the fight, before we could get reinforcements. There was no bank in front to protect my company, and the space between us and the foe was open and perfectly level. Every man of us knew it would be sure death to all to retreat, for we had behind us a bank seven feet high, made slippery by the wading and climbing back of the wounded, and where the foe could be at our heels in a moment. However, we had no idea of retreating, had the ground been twice as inviting; but taking in the situation only strung us up to higher determination. The regiment to the right of us was giving way, but just as the line was wavering and about to be hopelessly broken, Logan dashed up, and with the shriek of an eagle turned them back to their places, which they regained and held. Had it not been for Logan’s timely intervention, who was continually riding up and down the line, firing the men with his own enthusiasm, our line would undoubtedly have been broken at some point. For two hours the contest raged furiously, but as man after man dropped dead or wounded, the rest were inspired the more firmly to hold fast their places and avenge the fallen. The creek was running red with precious blood spilt for our  country. My bunkmate[1] and I were kneeling side by side when a ball crashed through his brain, and he fell over with a mortal wound. With the assistance of two others I picked him up, carried him over the bank in our rear, and laid behind a tree, removing from his pocket, watch and trinkets, and the same little mirror that had helped him make his last toilet but a little while before. We then went back to our company after an absence of but a few minutes. Shot and shell from the enemy came over thicker and faster, while the trees rained bunches of twigs around us.

country. My bunkmate[1] and I were kneeling side by side when a ball crashed through his brain, and he fell over with a mortal wound. With the assistance of two others I picked him up, carried him over the bank in our rear, and laid behind a tree, removing from his pocket, watch and trinkets, and the same little mirror that had helped him make his last toilet but a little while before. We then went back to our company after an absence of but a few minutes. Shot and shell from the enemy came over thicker and faster, while the trees rained bunches of twigs around us.

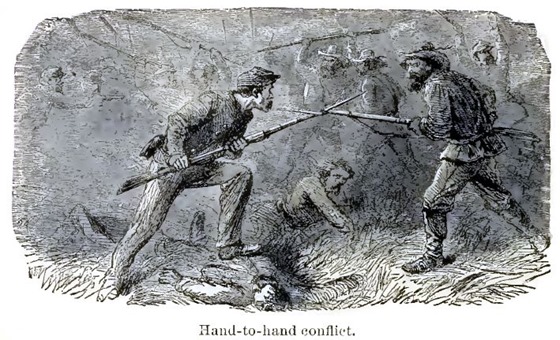

One by one the boys were dropping out of my company. The second lieutenant in command was wounded; the orderly sergeant dropped dead, and I find myself (fifth sergeant) in command of the handful remaining. In front of us was a reb in a red shirt, when one of our boys, raising his gun, remarked, “see me bring that red shirt down,” while another cried out, “hold on, that is my man.” Both fired, and the red shirt fell—it may be riddled by more than those two shots. A red shirt is, of course, rather too conspicuous on a battle field. Into another part of the line the enemy charged, fighting hand to hand, being too close to fire, and using the butts of their guns. But they were all forced to give way at last, and we followed them up for a short distance, when we were passed by our own reinforcements coming up just as we had whipped the enemy. I took the roll-book from the pocket of our dead sergeant, and found that while we had gone in with thirty-two men, we came out with but sixteen—one-half of the brave little band, but a few hours before so full of hope and patriotism, either killed or wounded. Nearly all the survivors could show bullet marks in clothing or flesh, but no man left the field on account of wounds. When I told Colonel Force of our loss, I saw tears course down his cheeks, and so intent were his thoughts upon his fallen men that he failed to note the bursting of a shell above him, scattering the powder over his person, as he sat at the foot of a tree.

Although our ranks have been so thinned by to-day’s battle our will is stronger than ever to march and fight on, and avenge the death of those we must leave behind. I am very sad on account of the loss of so many of my comrades, especially the one who bunked with me, and who had been to me like a brother, even sharing my load when it grew burdensome. He has fallen; may he sleep quietly under the shadows of those old oaks which looked down upon the struggle of to-day.

Although our ranks have been so thinned by to-day’s battle our will is stronger than ever to march and fight on, and avenge the death of those we must leave behind. I am very sad on account of the loss of so many of my comrades, especially the one who bunked with me, and who had been to me like a brother, even sharing my load when it grew burdensome. He has fallen; may he sleep quietly under the shadows of those old oaks which looked down upon the struggle of to-day.

We moved up to the town of Raymond and there camped. I suppose this will be named the battle of Raymond. The citizens had prepared a good dinner for the rebels on their return from victory, but as they actually returned from defeat they were in too much of a hurry to enjoy it. It is amusing now to hear the boys relating their experiences going into battle. All agree that to be under fire without the privilege of returning it is uncomfortable—a feeling which soon wears off when their own firing begins. I suppose the sensations of our boys are as varied as their individualities. No matter how brave a man may be, when he first faces the muskets and cannon of an enemy he is seized with a certain degree of fear, and to some it becomes an occasion of an involuntary but very sober review of their past lives. There is now little time for meditation; scenes change rapidly; he quickly resolves to do better if spared, but when afterward marching from a victorious field such good resolutions are easily forgotten. I confess, with humble pleasure, that I have never neglected to ask God’s protection when going into a fight, nor thanking him for the privilege of coming out again alive. The only thought that troubles me is that of falling into an unknown grave.

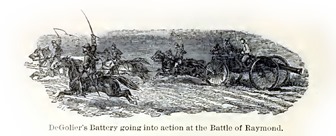

The battle to-day opened very suddenly, and when DeGolier’s battery began to thunder, while the infantry fire was like the pattering of a shower, some cooks, happening to be surprised near the front, broke for the rear carrying their utensils. One of them with a kettle in his hand, rushing at the top of his speed, met General Logan, who halted him, asking where be was going, when the cook piteously cried, “Oh General, I’ve got no gun, and such a snapping and cracking as there is up yonder I never heard before.” The General let him pass to the rear.

Thomas Runyan [2], of Company A, was wounded by a musket ball which entered the right eye, and passing behind the left forced it out upon his cheek. As the regiment passed, I saw him lying by the side of the road, tearing the ground in his death struggle.

[1] John Calvin Waddell, Corporal Co. E, 20th Ohio, killed May 12 1863.

[2] When the regiment was being mustered out in July, 1865, Thomas Runyan. who had been left for dead, visited the regiment. He said he came “to see the boys.” He was, of course, totally blind.

MAY 11TH.—We drew two days’ rations and marched till noon. My company, E, being detailed for rear guard, a very undesirable position. General Logan thinks we shall have a fight soon. I am not particularly anxious for one, but if it comes I will make my musket talk. As we contemplate a battle, those who have been spoiling for a fight cease to be heard. It does not even take the smell of powder to quiet their nerves—a rumor being quite sufficient.

We have no means of knowing the number of troops in Vicksburg, but if they were well generaled and thrown against us at some particular point, the matter might be decided without going any further. If they can not whip us on our journey around their city, why do they not stay at home and strengthen their boasted position, and not lose so many men in battle to discourage the remainder? We are steadily advancing, and propose to keep on until we get them where they can’t retreat. My fear is that they may cut our supply train, and then we should be in a bad fix. Should that happen and they get us real hungry, I am afraid short work would be made of taking Vicksburg.

Having seen the four great Generals of this department, shall always feel honored that I was a member of Force’s 20th Ohio, Logan‘s Division, McPherson’s Corps of Grant’s Army. The expression upon the face of Grant was stern and care-worn, but determined. McPherson’s was the most pleasant and courteous—a perfect gentleman and an officer that the 17th corps fairly worships. Sherman has a quicker and more dashing movement than some others, a long neck, rather sharp features, and altogether just such a man as might lead an army through the enemy’s country. Logan is brave and does not seem to know what defeat means. We feel that he will bring us out of every fight victorious. I want no better or braver officers to fight under. I have often thought of the sacrifice that a General might make of his men in order to enhance his own eclat, for they do not always seem to display the good judgment they should. But I have no fear of a needless sacrifice of life through any mismanagement of this army.

MAY 10TH—Left camp after dinner. Dinner generally means noon, but our dinner-time on the march is quite irregular. Advanced unmolested till within about three miles of Utica, and camped again at dark.

This forenoon my bunk-mate (Cal. Waddle) and I went to a house near camp to get some corn bread, but struck the wrong place, for we found the young mistress who had just been deserted by her negroes, all alone, crying, with but a scant allowance of provisions left her. She had never learned to cook, and in fact was a complete stranger to housework of any kind. Her time is now at hand to learn the great lesson of humanity. There has been a little too much idleness among these planters. But although I am glad the negroes are free I don’t like to see them leaving a good home, for good homes some of them I know are leaving. They have caught the idea from some unknown source that freedom means fine dress, furniture, carriages and luxuries. Little do they yet know of the scripture—”In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread.” I am for the Emancipation Proclamation, but I do not believe in cheating them. This lady’s husband is a confederate officer now in Vicksburg, who told her when he left she should never see a Yankee “down thar” Well, we had to tell her we were “thar,” though, and to our question what she thought of us, after wiping her eyes her reply was we were very nice looking fellows. We were not fishing for compliments, but we like to get their opinions at sight, for they have been led, apparently, to expect to find the Lincoln soldier more of a beast than human. At least such is the belief among the lower sort. Negroes and poor whites here seem to be on an equality, so far as education is concerned and the respect of the better classes. I have not seen a single school-house since I have been in Dixie, and I do not believe such a thing exists outside of their cities. But this war will revolutionize things, and among others I hope change this state of affairs for the better.

War is a keen analyzer of a soldier’s character. It reveals in camp, on the march and in battle the true principles of the man better than they are shown in the every-day walks of life. Here he has a chance to throw off the vicious habits of the past, and take such a stand as to gain a lasting reputation for good, or, if be dies upon the field, the glory of his achievements, noble deeds and soldierly bearing in camp will live in the memory of his comrades. Every soldier has a personal history to make, which will be agreeable, or not, as he chooses. A company of soldiers are as a family; and, if every member of it does his duty towards the promotion of good humor, much will be done toward softening the hardships of that sort of life.

This is Sunday, and few seem to realize it. I would not have known it myself but for my diary. I said, “boys this is Sunday.” Somebody asked, “how do you know it is?” I replied my diary told me. Another remarked, “you ought to tell us then when Sunday comes round so we can try to be a little better than on week days.” While in regular camps we have had preaching by the Chaplains, but now that we are on the move that service is dispensed with, and what has become of the Chaplains now I am unable to say. Probably buying and selling cotton, for some of them are regular tricksters, and think more of filling their own pockets with greenbacks than the hearts of soldiers with the word of God

MAY 9TH.—Orders this morning to draw two days’ rations, pack up and be ready to move at a moment’s warning. We drew hard-tack, coffee, bacon, salt and sugar, and stored them in our haversacks. Some take great care so to pack the hard-tack that it will not dig into the side while marching, for if a corner sticks out too much anywhere, it is only too apt to leave its mark on the soldier. Bacon, too, must be so placed as not to grease the blouse or pants. I see many a bacon badge about me—generally in the region of the left hip. In filling canteens, if the covers get wet the moisture soaks through and scalds the skin. The tin cup or coffee-can is generally tied to the canteen or else to the blanket or haversack, and it rattles along the road, reminding one of the sound of the old cow coming home. All trifling troubles like these on the march may be easily forestalled by a little care, but care is something a soldier is not apt to take, and he too often packs his “grub” as hurriedly as he “bolts” it. We were soon ready to move, and filled our canteens with the best water we have had for months. We did not actually get our marching order, however, until near three o’clock P. M., so that being anxious to take fresh water with us, we had to empty and refill canteens several times. As we waited for the order, a good view was afforded us of the passing troops, and the bristling lines really looked as if there was war ahead.

O, what a grand army this is, and what a sight to fire the heart of a spectator with a speck of patriotism in his bosom. I shall never forget the scene of to-day, while looking back upon a mile of solid columns, marching with their old tattered flags streaming in the summer breeze, and hearkening to the firm tramp of their broad brogans keeping step to the pealing fife and drum, or the regimental bands discoursing “Yankee Doodle” or “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” I say it was a grand spectacle—but how different the scene when we meet the foe advancing to the strains of “Dixie” and “The Bonny Blue Flag.” True, I have no fears for the result of such a meeting, for we are marching full of the prestige of victory, while our foes have had little but defeat for the last two years. There is an inspiration in the memory of victory. Marching through this hostile country with large odds against us, we have crossed the great river and will cut our way through to Vicksburg, let what dangers may confront us. To turn back we should be overwhelmed with hosts exulting on their own native soil. These people can and will fight desperately, but they cannot put a barrier in our way that we cannot pass. Camped a little after dark.

MAY 8TH—We were ready to continue our march, but were not ordered out. Some white citizens came into camp to see the “Yankees,” as they call us. Of course they do not know the meaning of the term, but apply it to all Union soldiers. They will think there are plenty of Yankees on this road if they watch it. The country here looks desolate. The owners of the plantations are “dun gone,” and the fortunes of war have cleared away the fences. One of the boys foraged to-day and brought into camp, in his blanket, a variety of vegetables—and nothing is so palatable to us now as a vegetable meal, for we have been living a little too long on nothing but bacon. Pickles taste first-rate. I always write home for pickles, and I’ve a lady friend who makes and sends me, when she can, the best kind of “ketchup.” There is nothing else I eat that makes me catch up so quick. There is another article we learn to appreciate in camp, and that is newspapers—something fresh to read. The boys frequently bring in reading matter with their forage. Almost anything in print is better than nothing. A novel was brought in to-day, and as soon as it was caught sight of a score or more had engaged in turn the reading of it. It will soon be read to pieces, though handled as carefully as possible, under the circumstances. We can not get reading supplies from home down here. I know papers have been sent to me, but I never got them. The health of our boys is good, and they are brimful of spirits (not “commissary”). We are generally better on the march than in camp, where we are too apt to get lazy, and grumble; but when moving we digest almost anything. When soldiers get bilious, they can not be satisfied until they are set in motion.

MAY 7TH.—Our company detailed and reported this morning at headquarters for picket duty, but not being needed, returned to camp. Were somewhat disappointed, for we preferred a day on picket by way of change.

Pickets are the eyes of the army and the terror of those who live in close proximity to their line. Twenty-four hours on picket is hardly ever passed without some good foraging.

We broke camp at ten o’clock A. M., and very glad of it. After a pleasant tramp of ten miles we reached Rocky Springs. Here we have good, cold spring water, fresh from the bosom of the hills.

We have met several of the men of this section who have expressed surprise at the great number of troops passing. They think there must be a million of “you’ns” coming down here. We have assured them they have not seen half of our army. To our faces these citizens seem good Union men, but behind our backs, no doubt their sentiments undergo a change. Probably they were among those who fired at us, and will do it again as soon as they dare. I have not seen a regular acknowledged rebel since we crossed the river, except those we have seen in their army. They may well be surprised at the size of our force, for this Vicksburg expedition is indeed a big thing, and I am afraid the people who were instrumental in plunging this country headlong into this war have not yet realized what evils they have waked up. They are just beginning to open their eyes to war’s career of devastation. They must not complain when they go out to the barnyard in the morning and find a hog or two missing at roll-call, or a few chickens less to pick corn and be picked in turn for the pot. I think these southern people will be benefited by the general diffusion of information which our army is introducing; and after the war new enterprise and better arts will follow—the steel plow, for instance, in place of the bull-tongue or old root that has been in use here so long to scratch the soil. The South must suffer, but out of that suffering will come wisdom.

MAY 6TH.—This day has been a hot one, but as our duties have not been of an arduous nature we have sought the shade and kept quiet. While in camp, the boys very freely comment upon our destination, and give every detail of progress a general overhauling. The ranks of our volunteer regiments were filled at the first call for troops. That call opened the doors of both rich and poor, and out sprang merchant, farmer, lawyer, physician and mechanics of every calling, whose true and loyal hearts all beat in unison for their country. The first shot that struck Sumpter’s wall sent an electric shot to every loyal breast, and today we have in our ranks material for future captains, colonels and generals, who before this war is ended will be sought out and honored.

It can not be possible that we are to be kept at this place much longer, for it is not very desirable as a permanent location. Of course we are here for some purpose, and I suppose that to be to prevent the enemy from assailing our line of supplies. As they are familiar with the country they can annoy us exceedingly without much loss to themselves. But after we have captured Vicksburg, and the history of Grant’s movements is known, we shall then understand why we guarded Hankinson’s Ferry so long. One of the boys said he thought Mr. Hankinson owed us something nice for taking such good care of his ferry for him. The variety of comments and opinions expressed in camp by the men is very curious. Some say we are going to surround Vicksburg, others think Grant is feeling for the enemy’s weakest point there to strike him, and one cool head remarked that it was all right wherever we went while Grant was leading, for he had never known defeat. Confidence in a good general stiffens a soldier—a rule that ought to work both ways. Surely no leader ever had more of the confidence of those he led than General Grant. He is not as social as McPherson, Sherman, Logan and some others, but seems all the while careful of the comfort of his men, with an eye single to success. Great responsibilities, perhaps, suppress his social qualities, for the present; for each day presents new obstacles to be met and overcome without delay. The enemy are doing all they can to hinder us, but let Grant say forward, and we obey.

Unable to sleep last night, I strolled about the camp awhile. Cause of my wakefulness, probably too much chicken yesterday. I appeared to be the only one in such a state, for the rest were

“Lost in heavy slumbers,

Free from toil and strife,

Dreaming of their dear ones,

Home and child and wife:

Tentless they are lying.

While the moon shines bright.

Sleeping in their blankets,

Beneath the summer’s night.”