Yellow Bluff, Fla.,

June 30, 1864.

Dear Sister L.:—

I know something how near to you the death of Almon comes. He was a comparative stranger to me. I had seen him but twice, once at home and once at Jacksonville, and of course I could not know him very intimately. His comrades spoke well of him and esteemed him highly, and he seemed to me like an excellent soldier and a good young man. I sympathize with you in your sorrow. Your grief is mine and your joy also.

My last letter from E. gives the intelligence that he too is among the host pressing on to Richmond, and I tremble lest in these days of terrible slaughter the next one may bring the news of a fearful wound, or some strange hand may tell me of his death in the field. I feel more anxious for him than I ever did for myself. You know how I have always felt about his going out and I have expressed my views freely to him, but now he is there, he shall hear no discouraging word from me. I have written to him to do his duty fearlessly and faithfully, and if he falls, to die with his face to the foe. He will do it. You will never blush for the cowardice of your brother, and my only fear is that he will be too rash. I glory in his spirit, while I tremble for his danger. Oh, I could hardly bear to give him up now, and yet I suppose his life and his proud young spirit are no more precious, no more dear to me or to you than thousands of others who have fallen and are to fall are to their friends. But I will not look forward to coming sorrow, but hope for the best.

This is the last night in June and very swiftly the month has passed away. The weather has been delightful, not near so warm as May. Almost every day we have had a refreshing shower.

We are in hopes to be ordered to Virginia, or we should not be disappointed if we were ordered there. The Seventh U. S. C. T. started day before yesterday and the Thirty-fifth went by to-day. It does seem hard that I should be lying here in idleness while my old comrades are marching on to victory or death. Perhaps it is for the best.

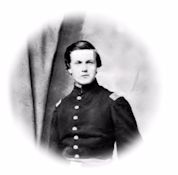

I have just been looking with pride at E.’s picture. Why cannot I look at yours? Isn’t it worth while to take a little trouble to send it to me? There must be a photographer in Panama.