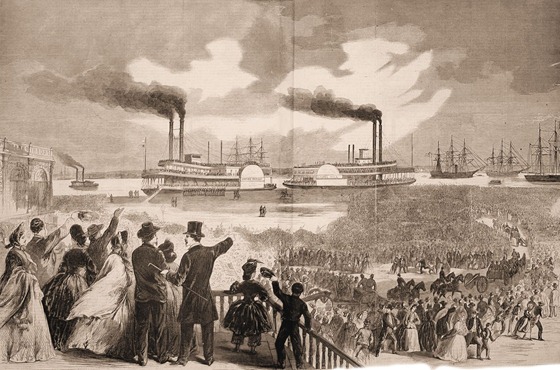

Scene on the Levee at New Orleans on the Departure of the Paroled Rebel Prisoners, February 20, 1863 – Sketched by Mr. Hamilton.

__________

EXTRAORDINARY EXCITEMENT IN NEW ORLEANS.

A VERY extraordinary exhibition of public feeling took place in New Orleans on Friday the 20th ult., which threw the whole city in the wildest excitement; but was, fortunately, attended with no serious consequences. We illustrate the scene on pages 184 and 185.

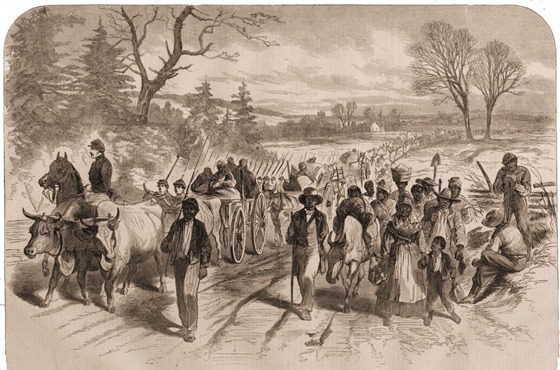

It having been publicly announced that a flag-of-truce boat would leave on Friday to convey some 382 paroled prisoners to Baton Rouge, and there exchange them on board a rebel vessel for Port Hudson, an immense concourse of the disloyal portion of the community congregated on the levee to see them go off. The Empire Parish, with the prisoners on board, was lying at the foot of Canal Street, and the Laurel Hill—moored immediately ahead of her—was selected by about 1000 at least, who crowded into and upon every part of her, to see the rebel prisoners and cheer them.

The Empire Parish had been advertised to leave at three o’clock, and it must have been as early as noon that the masses commenced to assemble. By two o’clock the whole levee, in its enormous width and extending all the way from Canal to Julia Street, was one dense sea of human heads; a large proportion of them females wearing secesh badges, and many openly waving little rebel flags—an insult not confined to their sex alone.

Seeing that matters were assuming a disgraceful if not alarming aspect, notice was sent to General Bowen, advising him of the fact, and suggesting the necessity of sending down some troops. The order was at once given, and soon a squad of the Twenty-sixth Massachusetts were on the ground, and a portion of a battery came threading its way through the crowd.

The scene at his moment was grand and exciting. The immense crowds on the levee swaying back by the advance of the soldiery—the Laurel Hill and the Empire Parish both one living mass of human beings cheering vociferously—and the balconies and windows facing the river teeming in every available spot, even to the roofs—the females screaming and waving their handkerchiefs, scarfs, flags, and parasols.

The order being given, the soldiers began to make the crowd move back; a delicate task not easy to effect, as the women were all in front, thus screening the men behind an impassable and invincible barrier of crinoline. The soldiers, however, behaved with perfect order, temper, and decency, making no reply to the insulting taunts from hundreds of the weaker sex, but, holding their muskets horizontally, gently made the crowd fall back. The balconies were also cleared of all their demonstrative occupants, and thus at last the whole mass was grumblingly dispersed, and the Empire Parish had to crawl off quietly in the night without that grand parting scene which the rebels evidently expected, and which the scene in the morning clearly promised. Upon the whole, it was a disgraceful and dangerous exhibition, and one which certainly ought to have been, and could have been, prevented had any ordinary means been used for avoiding its occurrence.