Written from the Sea islands of South Carolina.

St. Helena Island, July 17, 1862.

I do want to let you know the little particulars you speak of very much, but there are always so many great things to tell of here that I have no time. Just now we are going through “history” in the removal from Edisto of all the negroes there, consequent upon the evacuation of the island by our troops. The story is this — General McClellan wanting more soldiers, General Stevens and his regiment went North, and we had not enough soldiers left to guard Edisto, which lies near Charleston. So General Hunter ordered the evacuation of the island, first removing all the negroes who wished our protection, and that was all who were there. They embarked in one or two vessels, sixteen hundred in all, with their household effects, pigs, chickens, and babies “promiscuous.” Last night Captain Hooper went to see that they were comfortably established on this island. They have the fashionable watering-place given up to them, with all their old masters’ houses at their disposal. The superintendents laugh about it. They say the negroes go to St. Helenaville for their healths, and the white folks stay on the plantations. I suppose some of the places will be unhealthy, but ours is fortunately situated, as we have a cool wind from the sea every day. These negroes will be rationed and cared for. They say they will get in the cotton here that had to be abandoned when the black regiment was formed. They are quiet and good, anxious to do all they can for the people who are protecting them. They have not the least desire, apparently, to welcome back their old masters, nor to cling to the soil. They want only what Yankees can give them.

We are going to have another change in this household. Mr. Soule,[1] Mrs. Philbrick’s uncle, is coming to preside. He is just made General Superintendent of these two islands, and this will be his headquarters.

Mr. Pierce’s short visit on his return was very pleasant. He came at midnight, in his usual energetic fashion, and stayed some days. General Saxton, his successor, seems a very fine fellow, and most truly anti-slavery. He is quite interested in Nelly Winsor’s movements and plans, she having taken Eustis’ plantation to oversee, as well as this one. She is paid for this by Government fifty dollars per month. Her salary as teacher from the commission will probably soon cease. Ellen has a fine afternoon school and is doing remarkably well with it. She has two Sunday-School classes, one at church, one here. I help in the Sunday-School here and have a class of thirty-six or so at the church.

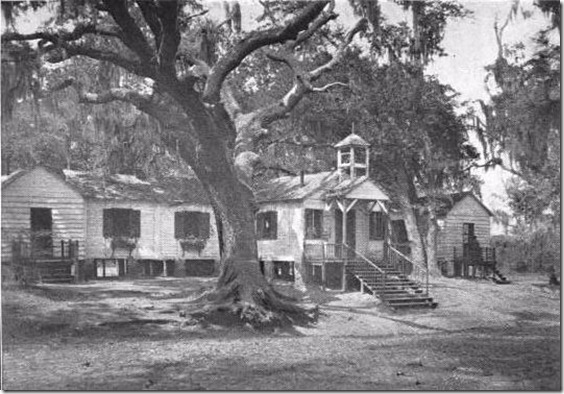

I will go over one day — an average day — to let you know how I spend my time. If Captain Hooper has to go to Beaufort by the early ferry, we have to get up by six; but if he does not, we lie till after eight, and we about equally divide the days between early and late rising. After breakfast, I feed my three mocking-birds, — how thankful I should be for a decent cage for them! — and then go to the Boston store or the cotton-house and pack boxes to go off to plantations, or clear up the store, or sell — the latter chiefly on Saturdays, when there is a crowd around the door laughing, joking, scolding, crowding. Ellen always goes to the stores when I do, and will stay, as she says she was commissioned expressly to take care of me and work with me. She makes this an excuse or a reason for insisting upon sharing every bit of work I do. About eleven or twelve I come in, wash, sleep, and lunch whenever my nap is out. In the afternoons I expect to write while Ellen has her school, for I do not help her in it, but so many folks come for clothing, or on business, or to be doctored, that I rarely have an hour. Then comes supper and dinner together at any time between six and ten that Captain Hooper gets here. About sundown, I, with Ellen, walk down the little negro street, or “the hill,” as they call it, — though it is as flat as a pond, — to attend my patients. I am sorry to say that Aunt Bess, whose ulcer I had nearly cured, has another on the same leg, and so my skill seems of less avail than I could hope. We had the prettiest little baby born here the other day that I ever saw, and good as gold. It is a great pet with us all. Indeed, it is almost laughable to see what pets all the people are and how they enjoy it. At church, at home, and in the field their own convenience is the first cared for, and compared to them the poor superintendents are “nowhar.” It is too funny to hear them ordering me around in the store — with real good-natured liking for mischief in it, too.

After dinner we sit awhile and talk in the parlor, but the mosquitoes give us no peace. To-night Ellen and I have taken our writing-desks and candle under our mosquito net. I am glad to have good fare. We have nice melons and figs, pretty good corn, tomatoes now and then, bread rarely; hominy, cornbread, and rice waffles being our principal breadstuffs. We have fish every day nearly, but fresh meat never — now and then turtle soup, though. Living on the “fat of the lamb ” is nothing to ours on the fat of the turtle. Our household servants are four in number, besides my Rina, who washes for me and does my chamber-work, besides waiting at table. She is the best old thing in the world and I hope I can take her North with me. … It is grand to run to my private store for nails and tacks, etc., and the sewing-things are invaluable. The pulverized sugar lasts well. Captain Hooper had a letter from Mr. P., in which he speaks of the pleasant times he had here. He will never have so pleasant again, I believe, because he was doing a good work for no pay, and that is a satisfaction not often to be had. The cotton crop here will be a success, I think, and the corn will be plentiful, unless we have some great storms. I wish you could see the wild flowers, the hedges of Adam’s-needle, with heads of white bells a foot or two through and four feet high; the purple pease with blossoms that look like dogtooth violets — just the size — climbing up the cotton-plant with its yellow flower, and making whole fields purple and gold; the passion flowers in the grass; the swinging palmetto sprays.

I send the music. It is not right, but will give you some idea. “Roll, Jordan, Roll” is the finest song.

[1] Richard Soule, Jr.