March 17, 1863 by Edwin Forbes.

Library of Congress image.

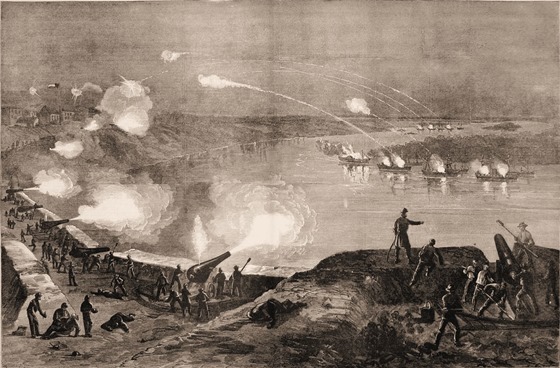

Our picture represents that moment in the fight when the “Hartford” has reached safety above the forts; the “Monongahela ” is turning to drift down, and the ” Mississippi ” is bursting into flames as the crew desert her under the fire of the Confederate batteries. Beacon-fires on either shore flash fitfully through the gloom, and with the locomotive head-lights on the lower banks enable the gunners to discover the position of the passing vessels. (Catalogue; Prang’s War Pictures.)

Library of Congress image.

ON the night of 14-15th March Admiral Farragut passed the rebel batteries at Port Hudson with his flag-ship, the Hartford, and the Albatross. He attacked the forts with his entire fleet, but all but the two vessels above named were repulsed, and the Mississippi, having grounded, was set on fire and abandoned. We illustrate the combat on pages 248 and 249, and subjoin the following condensed account of the affair from the Herald correspondence:

ON the night of 14-15th March Admiral Farragut passed the rebel batteries at Port Hudson with his flag-ship, the Hartford, and the Albatross. He attacked the forts with his entire fleet, but all but the two vessels above named were repulsed, and the Mississippi, having grounded, was set on fire and abandoned. We illustrate the combat on pages 248 and 249, and subjoin the following condensed account of the affair from the Herald correspondence:

The rebel batteries extend about four miles in length, with a gap here and there between. Below, just before the high bluff begins, a very large number of field batteries were placed in position. These batteries are by no means to be despised; for in such a narrow part of the river they are just as effective as siege guns, especially as they can be handled with far greater facility than ordnance of larger size. Proceeding upward, the regular fortifications commence. They seem to consist of three distinct ranges of batteries, numbering several in each range. It does not seem, however, that either of them mounts guns of very large calibre. The river now begins to trend to the west, forming a faint representation of a horseshoe, in the hollow of which the town of Port Hudson is situated. It is right in that hollow, and just below the town, that the most formidable battery—the central one—is situated, on the highest bluff. Four heavy guns appear to be mounted there in casemates. I say appear, because the flashes from these guns revealed nothing; but the flame from the muzzles showed that all beyond was in obscurity —precisely as would be the case with guns in casemate. The other guns, en barbette, or peering through open embrasures, revealed, when fired, something of the lay of the land behind and around, though but for a moment. Above the town are other batteries, only less formidable than those just below. Beyond these the high bluffs gradually subside into the general level of the surrounding country. Right opposite the principal batteries, on the right bank of the river, is the point of land on which the Mississippi grounded, in consequence of which she had to be set on fire and destroyed.

After describing the first shots from the Hartford, which were promptly returned from the rebel batteries, the correspondent thus describes the

And now was heard a thundering roar, equal in volume to a whole park of artillery. This was followed by a rushing sound, accompanied by a howling noise that beggars description. Again and again was the sound repeated, till the vast expanse of heaven rang with the awful minstrelsy. It was apparent that the mortar-boats had opened fire. Of this I was soon convinced on casting my eyes aloft. Never shall I forget the sight that then met my astonished vision. Shooting upward at an angle of forty-five degrees, with the rapidity of lightning, small globes of golden flame were seen sailing through the pure ether—not a steady, unfading flame, but corruscating, like the fitful gleam of a fire-fly—now visible, and anon invisible. Like a flying star of the sixth magnitude, the terrible missile—a 13-inch shell—nears its zenith, up and still up—higher and higher. Its flight now becomes much slower, till, on reaching its utmost altitude, its centrifugal force becomes counteracted by the earth’s attraction; it describes a parabolic curve, and down, down, it comes, bursting, it may be, ere it reaches terra firma, but probably alighting in the rebel works ere it explodes, where it scatters death and destruction around.

The Richmond had by this time got within range of the rebel field batteries, which opened fire on her. I had all along thought that we would open fire from our bow guns, on the topgallant forecastle, and that, after discharging a few broadsides from the starboard side, the action would be wound up by a parting compliment from our stern chasers. To my surprise, however, we opened at once from our broadside guns. The effect was startling, as the sound was unexpected; but beyond this I really experienced no inconvenience from the concussion. There was nothing unpleasant to the ear, and the jar to the ship was really quite unappreciable. It may interest the uninitiated to be informed how a broadside is fired from a vessel-of-war. I was told on board the Richmond that all the guns were sometimes fired off simultaneously, though it is not a very usual course, as it strains the ship. Last night the broadsides were fired by commencing at the forward gun, and firing all the rest off in rapid succession, as fast almost as the ticking of a watch. The effect was grand and terrific; and, if the guns were rightly pointed—a difficult thing in the dark, by-the-way—they could not fail in carrying death and destruction among the enemy.

Of course we did not have every thing our own way; for the enemy poured in his shot and shell as thick as hail. Over, ahead, astern, all around us, flew the death-dealing missiles, the hissing, screaming, whistling, shrieking, and howling of which rivaled Pandemonium. It must not be supposed, however, that because our broadside guns were the tools we principally worked with, our bow and stern chasers were idle. We soon opened with our bow 80-pounder Dahlgren, which was followed up not long after by the guns astern, giving evidence to the fact that we had passed some of the batteries.

Soon after firing was heard astern of us, and it was soon ascertained that the Monongahela, with her consort, the Kineo, and the Mississippi, were in action. The Monongahela carries a couple of two hundred-pounder rifled Parrott guns, besides other ticklers. At first I credited the roar of her amiable two hundred-pounders to the “bummers,” till I was undeceived, when I recalled my experience in front of Yorktown last spring, and the opening of fire from similar guns from Wormley’s creek. All I can say is, the noise was splendid. The action now became general. The roar of cannon was incessant, and the flashes from the guns, together with the flight of the shells from the mortar boats, made up a combination of sound and sight impossible to describe. To add to the horrors of the night, while it contributed toward the enhancement of a certain terrible beauty, dense clouds of smoke began to envelop the river, shutting out from view the several vessels and confounding them with the batteries. It was very difficult to know how to steer to prevent running ashore, perhaps right under a rebel battery or into a consort. Upward and upward rolled the smoke, shutting out of view the beautiful stars and obscuring the vision on every side. Then it was that the order was passed, “Boys, don’t fire till you see the flash from the enemy’s guns.” That was our only guide through the “palpable obscurity.” Intermingled with the boom of the cannonade arose the cries of the wounded and the shouts of their friends, suggesting that they should be taken below for treatment. So thick was the smoke that we had to cease firing several times, and, to add to the horrors of the night, it was next to impossible to tell whether we were running into the Hartford or going ashore, and, if the latter, on which bank, or whether some of the other vessels were about to run into us or into each other. All this time the fire was kept up on both sides incessantly. It seems, however, that we succeeded in silencing the lower batteries of field-pieces.

This phrase is familiar to most persons who have read accounts of sea-fights that took place about fifty years ago; but it is difficult for the uninitiated to realize all the horrors conveyed in these three words. For the first time I had, last night, an opportunity of knowing what the phrase really meant. The central battery is situated about the middle of the segment of a circle I have already compared to a horseshoe in shape, though it may be better understood by the term “crescent.” This battery stands on a bluff so high that a vessel in passing immediately underneath can not elevate her guns sufficiently to reach those on the battery; neither can the guns on the battery be sufficiently depressed to bear on the passing ship. In this position the rebel batteries on the two horns of the crescent can enfilade the passing vessel, pouring in a terrible crossfire, which the vessel can return, though at a great disadvantage, from her bow and stern chasers. We fully realized this last night; for, as we got within short range, the enemy poured into us a terrible fire of grape and canister, which we were not slow to return—our guns being double-shotted, each with a stand of both grape and canister. Every vessel in its turn was exposed to the same fiery ordeal on nearing the centre battery, and right promptly did their gallant tars return the compliment. This was the hottest part of the engagement. We were literally muzzle to muzzle, the distance between us and the enemy’s guns being not more than twenty yards, though to me it seemed to be only as many feet. In fact, the battle of Port Hudson has been pronounced by officers and seamen who were engaged in it, and who were present at the passage of Fort St. Philip and Fort Jackson, below New Orleans, and had participated in the fights of Fort Donelson, Fort Henry, Island No. 10, Vicksburg, etc., as the severest in the naval history of the present war.

Matters had gone on in this way for nearly an hour and a half—the first gun having been fired at about half past eleven o’clock—when, to my astonishment, I heard some shells whistling over our port side. Did the rebels have batteries on the right bank of the river? was the query that naturally suggested itself to me. To this the response was given that we had turned back. I soon discovered that it was too true. Our return was, of course, more rapid than our passage up. The rebels did not molest us much, and I do not believe one of their shots took effect while we were running down rapidly with the current. It was a melancholy affair, for we did not know but what the whole expedition was a failure; neither could we tell whether any of our vessels had been destroyed, nor how many. We had the satisfaction of learning soon afterward, however, that the Hartford and Albatross had succeeded in rounding the point above the batteries. All the rest were compelled to return. We soon came to anchor on the west side of Prophet Island, so near to the shore that the poop-deck was strewn with the blossoms and leaves of the budding trees that we brushed back. As I passed the machinery of the vessel, on my way forward, I was shown a large hole that had been made by an eighty-pounder solid conical shell, which had passed through the hull of the ship, damaging the machinery so as to compel us to return. (Harper’s Weekly, April 18, 1863)

Admiral Farragut’s fleet engaging the rebel batteries at Port Hudson, March, 14th 1863.

Currier & Ives.

Library of Congress image.

Marriage of Captain Daniel Hart and Nellie Lammond, March 12, 1863.

______

On the 12th inst., marriage rites were celebrated in camp, this being the first occasion of the kind that has ever transpired in the army of the Potomac. Of course it “drew,” as all novelties do, and created a sensation in camp for a week preceding the affair. We, being on the staff, of course received a card…

(Troy NY Daily Times, March 24, 1863)

_____

WE reproduce on page 216 a picture of Mr. Waud’s, representing A MARRIAGE IN THE CAMP OF THE SEVENTH NEW JERSEY VOLUNTEERS in the Army of the Potomac. Mr. Waud writes:

“An event to destroy the monotony of life in one of Hooker’s old regiments. The camp was very prettily decorated, and being very trimly arranged among the pines, was just the camp a visitor would like to see. A little before noon the guests began to arrive in considerable numbers. Among them were Generals Hooker, Sickles, Carr, Mott, Hobart Ward, Revere, Bartlett, Birney, Berry, Colonel Dickinson, and other aids to General Hooker; Colonels Burling, Farnham, Egan, etc. Colonel Francine and Lieutenant-Colonel Price, of the Seventh, with the rest of the officers of that regiment, proceeded to make all welcome, and then the ceremony commenced. In a hollow square formed by the troops a canopy was erected, with an altar of drums, officers grouped on each side of this. On General Hooker’s arrival the band played Hail to the Chief, and on the approach of the bridal party the Wedding March. It was rather cold, windy, and threatened snow, altogether tending to produce a slight pink tinge on the noses present; but the ladies bore it with courage, and looked, to the unaccustomed eyes of the soldiers, like real angels in their light clothing. To add to the dramatic force of the scene, the rest of the brigade and other troops were drawn up in line of battle not more than a mile away to repel an expected attack from Fredericksburg. Few persons are wedded under more romantic circumstances than Nellie Lammond and Captain De Hart. He could not get leave of absence, so she came down like a brave girl, and married him in camp. After the wedding was a dinner, a ball, fire-works, etc.; and on the whole it eclipsed entirely an opera at the Academy of Music in dramatic effect and reality.” (Harper’s Weekly, April 4, 1863)

Drawing by Alfred R. Waud, Maarch 18, 1863.

Library of Congress image.

Marriage at the camp of the 7th N.J.V. poster available at Zazzle.com

WE devote pages 244 and 245 to illustrations of the HEAD-QUARTERS OF THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC, from sketches by Mr. A. R. Waud.

WE devote pages 244 and 245 to illustrations of the HEAD-QUARTERS OF THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC, from sketches by Mr. A. R. Waud.

Mr. Waud writes:

“The term headquarters’ conveys but a vague idea to the uninitiated. Most people are aware that the general lives and has his tent there, but of the necessity and use of the large train of

“The term headquarters’ conveys but a vague idea to the uninitiated. Most people are aware that the general lives and has his tent there, but of the necessity and use of the large train of  officers that accompany the general few out of the army have a correct idea. In the first place, the general must have his personal aids, whose duty it is to be always in attendance, to assist their commander in his plans, carry dispatches of importance, make themselves

officers that accompany the general few out of the army have a correct idea. In the first place, the general must have his personal aids, whose duty it is to be always in attendance, to assist their commander in his plans, carry dispatches of importance, make themselves  conversant with the position of the army and the roads, and in battle direct, under the general’s orders, the movements of the various corps, etc., etc. The chief of staff, whose tent is always near the

conversant with the position of the army and the roads, and in battle direct, under the general’s orders, the movements of the various corps, etc., etc. The chief of staff, whose tent is always near the  general’s, has a very onerous position. He must keep himself accurately posted on the actual condition of the army in all its departments, the intention and results of its movements, reconnoissances, etc.

general’s, has a very onerous position. He must keep himself accurately posted on the actual condition of the army in all its departments, the intention and results of its movements, reconnoissances, etc.  Through him the general’s orders are transmitted, and it is his duty to furnish the commander-in-chief and the head of the War Department tables of the strength and position of corps and posts,

Through him the general’s orders are transmitted, and it is his duty to furnish the commander-in-chief and the head of the War Department tables of the strength and position of corps and posts,  reports of operations, and all necessary information. Next to the commander, the chief of staff is the man of the whole army who can do the most good if he is capable, and the most harm if deficient in ability.

reports of operations, and all necessary information. Next to the commander, the chief of staff is the man of the whole army who can do the most good if he is capable, and the most harm if deficient in ability.

“The remainder of the officers of head-quarters are chiefs of the departments in which the army is divided and their aids. The Adjutant-General’s department, through which orders are published, reports and returns received and disposed of, tables formed of the state and detail of the army, records made, and much more. The Engineers’, whose duty it is to construct fortifications, field defenses, roads, bridges, etc., and remove obstructions. The Topographical Engineers’, whose duty it is to survey and map the country in which the army is to operate, attend reconnoissances, examine routes of communication by land and water both for supplies and military movements, and lay out new roads. The Chief of Artillery, in a siege or battle, directs the position of the artillery, and is responsible for the condition of that arm of the service. The Chief of Cavalry has similar duties in the cavalry. The Chief of Ordnance has charge of and furnishes all ordnance and ordnance stores for the military service; also equipments for mounted troops. The Inspector-General’s duties are to inspect and report upon stores and animals, and every thing required to keep the army in good condition. The Medical Director attends to the entire working of that department, and after a battle makes lists of the killed and wounded; and at other times regulates the management of the hospitals, the distribution of medical supplies, etc. The Chief Commissary, through whom the army is fed. The Chief Quarter-master, by whom it is clothed, provided with tents and transportation. The Provost-Marshal General, who receives prisoners, and attends to the police of the army, including the secret-service department. The Chief Signal-officer, and many minor departments or sub-departments, such as the telegraph-office, the post-office, the balloon party, and others—all tend, with their necessary complement of clerks for office-work, orderlies for out-door purposes, servants, and grooms, to swell the proportions of the camp at head-quarters, which is, in fact—under the orders of the War Department —the seat of government, the metropolis, or capital, of the community which is formed by the presence of the army.” (Harper’s Weekly, April 18, 1863)