Camp near Port Royal, November 9, 1862.

The day before yesterday we had a snow, and the weather is now quite cold. Winter seems to have set in, and it finds us sadly prepared for it. A large number of our soldiers are entirely barefooted, and very many without blankets. Living in the open air, without tents and with a very small supply of axes to cut wood for fires, there is much suffering. Those of our people who are living at home in comfort have no conception of the hardships which our soldiers are enduring. And I think they manifest very little interest in it. They are disposed to get rich from the troubles of the country, and exact from the Government the highest prices for everything needed for the army. I trust the Government will soon take the matter in hand, fix its own prices, and take what it wants for the army. Everything here indicates that we move to-morrow— where, there is no telling. But I trust we may soon find ourselves settled for the winter. If active operations were suspended for the winter, our men could soon build huts and make themselves comfortable. If, however, we have active operations, the sufferings of our men must be intense.

So you growl about Sunday letters. They are written on that day because all work in the army is suspended on that day and I always have leisure then. They are not interesting, you say. I am sorry for it. It is because I have but little to write about that would interest you. They always tell you I am alive and doing well. Isn’t that always interesting intelligence?

You never mentioned in your letter which company White Williamson is in. Let me know and I will go to see him. Give my love to Martha, and tell her I say she has good quarters in Lexington and she had better stay there. Our army is a moving concern, and there is no telling where it will be a month hence. Possibly we may be here, quite as likely at Richmond.

You speak of the army as my idol, but you never were more mistaken. I had a good deal rather live in a house than a tent, though I can bear the change, as there is no helping it. I had a good deal rather be with you and the children than with my idol, the army, your opinion to the contrary notwithstanding. And now, Growler, good-bye.

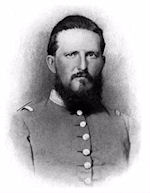

P. S. Since that was written, I have received an order conferring upon me the title of Brigadier-General and assigning me to the command of Jackson’s old brigade. I made no application for it, and if I had consulted my own inclination should have been disposed to remain in my present position.